In the Summertime when the weather is hot

You can stretch right up and touch the sky

From In the Summertime by Ray Dorset, performed by Mungo Jerry (1970).

When the heat is on, so are gliders. Thermals can mean a rough ride for smaller powered aircraft, but they’re the powerhouses of gliding. They allow experienced pilots to stay in the air for up to 10 hours and cover 700 to 1000 kilometres.

Gliding can be an exhilarating experience, but one which requires careful planning to minimise the risks of dehydration, hyperthermia, eye damage, skin cancer and remote outlandings.

It can be relatively cool at altitude under thermal-producing cumulus, but the same can’t be said when flying between thermals on a sunny day under a Perspex canopy, where temperatures can be 20 degrees or more above the ambient temperature.

The body has to work hard to keep its temperature close to 37 degrees Celsius. Hyperthermia sets in when the body produces or absorbs more heat than it can dissipate; at 40 degrees it can become life-threatening.

So gliding is sweat-producing work, akin in many ways to endurance running, and with similar hydration requirements.

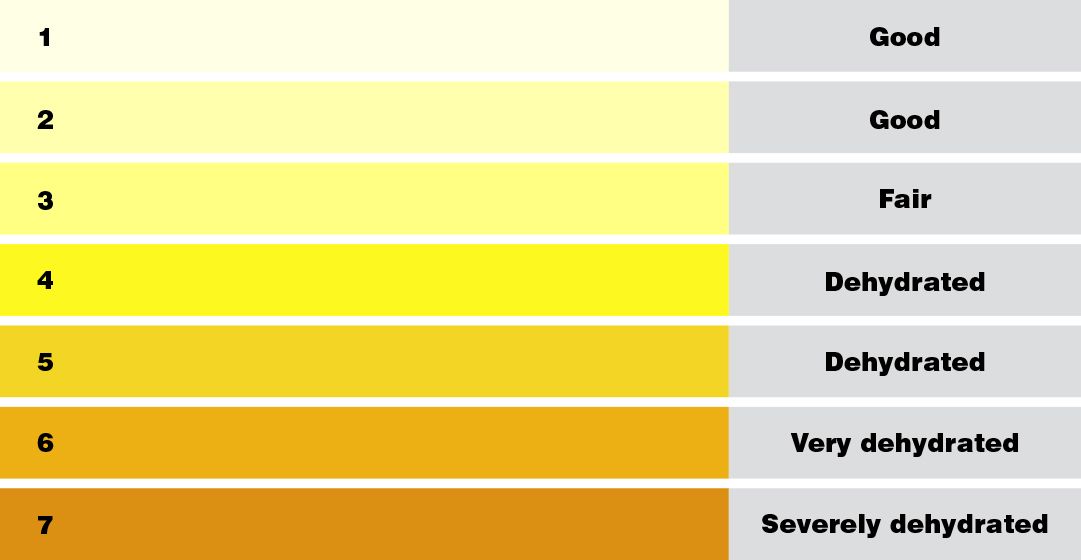

The golden rule is to keep drinking, because in the heat of summer and the confines of a cockpit, it’s possible to lose up to eight litres of fluid in a day. Hydrate early and often, and drink about 250 ml every 30 minutes. Thirst is a sign that you are already dehydrated.

The Australian Gliding Federation’s Executive Manager Operations, Chris Thorpe, says that pilots should carry at least two litres of fluids, preferably electrolyte sports drinks, and foods such as fruit which minimise the digestive system’s demand for water.

Fluid in, fluid out

‘If you’re not peeing, you’re not hydrated,’ Mr Thorpe says. His glider is equipped with a device to collect and expel urine, but there are other options for male and female endurance pilots, including incontinence pads.

The dangers of heat exhaustion and dehydration are real. Not long ago, an Australian glider pilot passed out at about 200 ft above the ground while making an outlanding. Luckily, he survived.

The dangers of heat exhaustion and dehydration are real. Not long ago, an Australian glider pilot passed out at about 200 ft above the ground while making an outlanding. Luckily, he survived.

While most gliders are well ventilated, the pilot is exposed to direct radiant heat. A broad-brimmed hat may not be practical in the confines of a glider, and baseball-style caps do not provide protection to the ears or neck. For this reason, many glider pilots wear that essential fashion accessory, the terry towelling bucket-style hat. Long-sleeve shirts and gloves are advisable, and sunscreen is a must.

Put on the SPOT

The possibility of an outlanding in unfamiliar territory is another consideration for long-distance gliders, particularly where there is no mobile phone coverage. Chris Thorpe points out that landing near a farmhouse or other building does not guarantee assistance will be available, since an increasing number are unoccupied or abandoned. He advises pilots to carry a SPOT or similar device in order to contact ground crew or family.

Out of sight: make sure the eyes have it

Anyone flying above 10,000 feet in an unpressurised aircraft needs to use supplemental oxygen to prevent hypoxia. But there’s another good reason.

Stephen Dain, Emeritus Professor of Optometry at the University of NSW, says that the retina of the eye is the most oxygen-demanding part of the body. Colour vision can deteriorate above 8000 feet.

Exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation is a potential source of harm for all aviators and its intensity increases by about 10 per cent for every 3300 feet. Glare and UV are a particular problem when flying above cloud or over snow.

The plastics used in sunglasses are UV absorbing. In Australia, all sunglasses must meet the consumer product safety standard based on Australian/New Zealand Standard AS/NZS 1067.1:2016 and offer UV protection. Darker sunglasses are better at reducing sunglare and have stricter UV requirements, but very good UV protection can also be had from some lighter tinted sunglasses. Wraparound-style sunglasses stop reflected radiation, including UV that can cause pterygium, a pink growth on the front of the eyeball.

Fashion conscious pilots can spend hundreds of dollars on a pair of cool looking sunnies—but they may not give you any more protection. Professor Dain ran a laboratory which tests products ranging from sunglasses to high-visibility garments. Of the thousands of sunglasses it tests, less than one a year fails to meet UV protection requirements.

Non-prescription eyewear is classified from 0 (fashion spectacles with little or no tinting) to 4 (very dark). Category 4 sunglasses must be labelled as not suitable for driving and may generally be too dark to be practical for flying. Look for the category and warnings on swing tags or stickers.

Sunglasses with gradient tints may be a good solution for dealing at the same time with the glare of the outside world and the darker environment of the cockpit.

Not recommended for flying above snow or cloud are these traditional Inuit snow goggles.

So remember: stay cool, stay hydrated, stay covered, wear your sunnies and fly within your personal limits and that of your aircraft.

“It can be relatively cool at altitude under thermal-producing cumulus” – sorry, but Cumulus do not produce Thermals, sometimes Thermals produce Cumulus depending on the atmospheric moisture level.

Nice article but why don’t you have a picture of a glider to go with the article? The trike really has nothing to do with the article or gliding.

Hi Cath,

There was a mix-up with the pictures, now corrected,

the FlightsafetyAustralia.com team

The other side of this equation is over-hydration or hypernatremia. This is far more dangerous than dehydration and even the young have commonly died from it. It is a degenerative process that once started, is difficult to stop. It arises from salt dilution in the blood plasma leading to osmosis and swelling of brain cells. Rapid medical intervention is required but unfortunately well meaning bystanders can administer even more water thinking it is dehydration.

Very dangerous. Too much drinking without salt replacement is dangerous. We should be careful about the current dogmatism in regard to dehydration.

Hi Robert,

Thanks for a useful addition to the discussion,

the FlightsafetyAustralia.com team

overhydration leads to hyponatraemia, not hypernatraemia.

[…] Like their colleagues chasing thermals during long cross-country flights in summer, the pilots face a hostile external environment—but it’s extreme cold rather than scorching temperatures and the risk of dehydration. […]