It’s still being made, but becoming a rare sight on the massive Boeing production line in Everett, Washington state, US, as its near 50-year reign as queen of the skies draws to an end. In the history of aviation, the Boeing 747 will be remembered as the aircraft that ushered in the age of mass travel and as a type that was introduced in the early jet age and retired in the digital age.

Since September 2016, Boeing has produced only one 747 every two months—compared to five a month for the 777 and 14 a month for the 787 aircraft. Sales of the current 747-8 model have been modest, and those still on order are freighters or replacements for US Air Force One.

The Boeing 747 was the wonder of the age when it went into commercial service with Pan Am in January 1970—the same year that Melbourne’s Tullamarine Airport, designed for 707-sized aircraft, opened.

The precursor to the 747 was a US Air Force project for a long-range transport aircraft larger than the C-141 Starlifter. The winning design was the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy, though the Boeing’s design also used the concept of a nose door and raised cockpit. This carried over to the 747. It was thought at the time that supersonic aircraft would replace conventional intercontinental passenger aircraft and that the 747 would become primarily a freighter—hence the raised cockpit to allow loading through a lift-up nose. Boeing expected to sell about 400 of the new design.

The 747 was conceived in an age of rapid growth in demand for air travel, led by the popularity of the 707 and the Douglas DC-8. Pan Am approached Boeing for a larger aircraft, hoping that it would help relieve congestion at some airports. The first order for the 747-100 was by Pan Am in April 1966.

While a full-loaded 747 had a lower operating cost per seat than other aircraft, this didn’t hold true with more modest loadings. The 1973 oil crisis reduced passenger numbers and some airlines found themselves with too few passengers to make 747 services economically viable. For example, Delta Airlines sold its five 747-100s in the mid-1970s, after selling as few as 100 of the 370 seats on some of its domestic routes. It later inherited 747-400s from its merger with Northwest Airlines in 2009, but will retire the last of them by the end of this year.

There were early concerns that bigger didn’t necessarily mean better when it came to safety—and in particular the potential for many casualties in the event of a crash.

Those fears were not unfounded. There have been more than 60 accidents among the 1553 or so 747s which have rolled off the assembly line, involving more than 3700 fatalities. However, few of these accidents have been attributed to design flaws.

Two 747s were involved in the worst accident in aviation history when, on March 27 1977, they collided on a foggy runway at what is now Tenerife North Airport, killing 583 passengers and crew. Lessons learned from the Tenerife crash formed part of the then new and controversial doctrine of cockpit resource management, now crew resource management (CRM). CRM’s mission was to avoid any repeat of the dreadful situation on the KLM 747 that inadvertently took-off without clearance. The flight engineer had tactfully asked, ‘Did he not clear the runway, the Pan American?’ to which the captain, who was possibly anxious to avoid exceeding maximum duty time after a delay, replied with an emphatic, but mistaken, ‘Yes’.

A 747 was involved in the worst single-aircraft aviation disaster, when Japan Airlines flight 123 crashed in August 1985, killing all but four of the 524 on board. The aircraft lost its hydraulic controls and its vertical fin after the rear pressure bulkhead blew out, 12 minutes into the flight. The cause of the failure was found to be a faulty repair made seven years previously, where only one row of rivets had been used to hold the bulkhead in place.

Other significant 747 crashes include the destruction of El Al flight 1862, a 747 freighter that crashed into a block of flats in Amsterdam, in The Netherlands, after an engine detached from the right wing and dislodged the other engine, and a section of the leading edge. All 747s had to be fitted with new engine pylon fuse pins after the investigation found these had failed due to metal fatigue. A crash in Taiwan the year before had had a similar cause, but killed only the freighter’s crew.

The in-flight break-up in 1996 of TWA flight 800 was attributed to an explosion in the centre fuel tank believed to have been sparked by ageing and brittle wiring.

The overall safety picture during the 747 years, however, is one of continuous improvement. In 1970 there were 78 fatal airliner accidents, killing 1475 people. In 2016, the numbers were 17 accidents and 258 dead, despite passenger numbers having grown by a factor of 10, from 300 million to more than 3 billion.

The 747-300 series, introduced in 1980, had the familiar stretched upper deck. The acronym SUD was soon changed to EUD (extended upper deck) when it was realised that in medical parlance it stood for sudden unexplained death. It is also the ICAO code for Sudan Airways. The -400 series retained the long, upper deck and introduced electronic flight displays and a two-person flight crew, doing away with the role of flight engineer.

In December 2000, Qantas became the first airline to order the 747-400ER series, and it took delivery of the last of that model in July 2003. Its place as Qantas’s flagship aircraft was taken over by the Airbus A380 in 2008.

Yet the end may also be in sight for the A380, whose commercial debut was only 10 years ago. Production was cut to 20 or so this year, and 12 from next year. Emirates, which has a fleet of nearly 100 A380s, has deferred some of its orders.

Four-engine aircraft, the default configuration for jet airliners since the de Havilland Comet, are falling out of favour. One of their greatest commercial threats is Boeing’s own twin-engine 777. One driver of the twin-engined evolution is increasingly permissive extended operations certifications (ETOPS). ETOPS refers to the maximum distance, in flying time, that a twin-engine air transport aircraft can operate from a diversion airport, should one engine fail. In practice, ETOPS governs how far from land a twin engine aircraft can fly. The original ETOPS certifications of the 1980s were ETOPS 120, allowing flight two hours away from the nearest diversion airport. The Airbus A350XWB was certified to ETOPS 370 in 2014. ETOPS was extended to aircraft with more than two engines in 2007 and the A350XWB’s ETOPS rating exceeds that of the 747-8, which is approved to ETOPS 330.

Other nullifying trends include the move away from hub-and-spoke operations towards a model based on smaller aircraft flying to smaller airports. Given the choice, passengers want these direct flights. Thus Qantas’s eight two-engine 787 Dreamliners will each have 236 seats, compared with between 353 and 364 for the 747-400 and -484 for the Airbus 380.

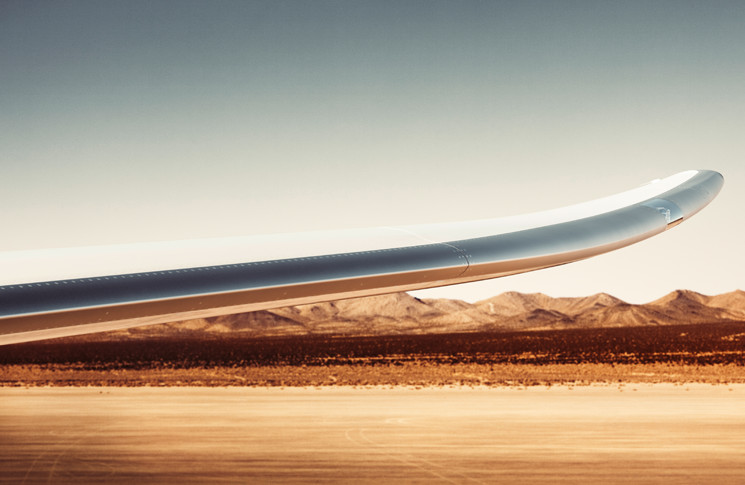

With the introduction of the Dreamliner, Qantas is expected to retire three of its 747s in mid-2018, followed by another two about a year later. It has not announced a retirement date for the remaining six 747s but the runway is in sight for the 747 generally and maybe for all four-engined airliners. Examples will no doubt fly for many years after production ceases, but unlike the immortal Douglas DC-3, its pressurised fuselage will have a finite, if long, lifetime.

The original jumbo jet will, and should be, fondly remembered. On its watch, airline travel went from being a regular generator of gory and distressing front-page stories to the safest way to travel on a per unit distance basis. That, and mass international tourism, shall be its legacies.

Even when they will not be flying any more in the (hopefully) distant future, they would always do so in the minds of those who like me, grew up with the mythical Boeing 747. Long live the Queen of the skies!

Francisco : Don’t worry mate.I reckon that like the venerable DC 3,They will still ply the skies as a freighter for years to come.They might even become as venerable as the DC3,Lets hope so anyway.After all they as yet do not have a compatable replacement as the above mentioned freighter/cargo carrier.Not yet that is

[…] including ours, for the Boeing 747 may have been premature: Cargo operator UPS Airlines placed an order last week […]

[…] later, the fall-back position of its freight hauling ability is keeping the 747 in production. As Flight Safety Australia discussed in 2017, factors ranging from the age of the basic design to the changing nature of international air […]

[…] Other more fuel-efficient twin-engine designs such as the Boeing 777, 787 and Airbus A350, will continue this role when aviation recovers, but no current aircraft will ever have the world-changing impact of the original ‘Jumbo Jet’. […]