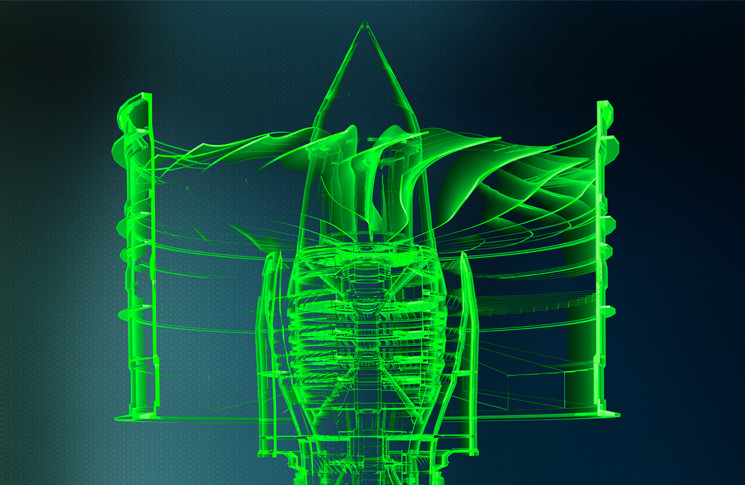

Aircraft engine manufacturer GE Aviation says that its new advanced turboprop (ATP) engine will have 12 components produced on a 3D printer, replacing 855 conventionally-made parts.

A report in Aviation Week says that the engine will be run for the first time later this year at the GE engine factory in Prague (the former Walter Engine Company) and will power Cessna’s new Denali turbine single aircraft when it makes its first flight next year.

GE says that the engine is designed to run on 20 per cent less fuel and produce 10 per cent more power than the equivalent Pratt and Whitney Canada PT6. It will also use full authority digital engine control (FADEC) for the first time on a civilian turboprop, replacing three engine controls with one lever.

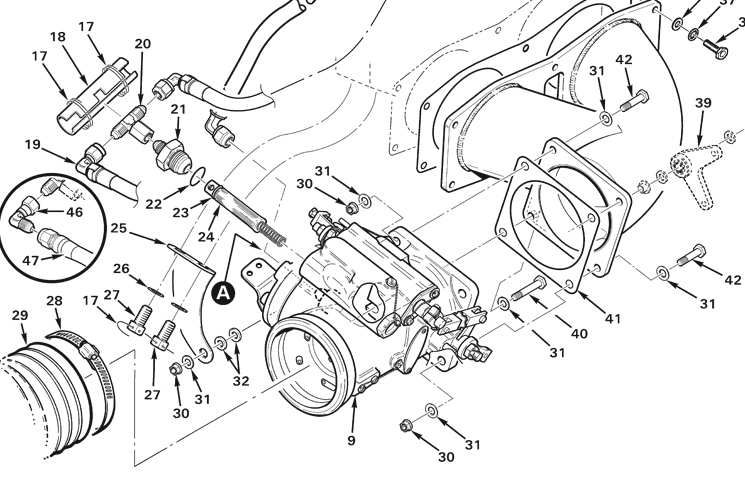

The engine takes advantage of additive manufacturing (3D printing) technologies developed for GE Aviation’s T901 turboshaft engine, which has successfully completed prototype testing with the US Army. The T901 makes use of various additively manufactured parts.

GE’s announcement continues the trend towards 3D printing in aviation. Flight Safety Australia reported last year that meals giant Alcoa would supply Airbus with 3D printed fuselage and engine pylon components made of titanium, with benefits in both lightness and strength.

The technology has also been used for smaller components, including Airbus plastic cabin fittings window pipes for the Bae146.

3D printing uses a moving laser to create successive layers of hard material from liquid or powder ‘feedstock’ to create a complex three-dimensional object. A 2015 report by consultant Wohlers Associates predicted the worldwide 3D printing industry would grow from $A4.1 billion in revenue in 2013 to $A17 billion by 2018, and exceed $A27 billion in worldwide revenue by 2020.

Comments are closed.