By a Flight Safety Australia reader

As a fresh PPL pilot, I was always thrilled when I got to navigate across the state all by myself. The sense of achievement I got from sitting in an aluminium tube that hurtles through the sky at 200 km/h, and somehow ends up at a predetermined location because of your inputs, was what fascinated me about flying.

It was during February when I started my navigation flights to build hours towards my commercial pilot’s licence. Flying from a school based in Melbourne, this meant generally excellent weather and lots of new places to explore.

On one particular Saturday in February, I had a solo cross-country flight booked in a Cessna 172. The day before the flight, I had put a lot of effort into creating a thorough flight plan to make things easier for me on the flying day. My route would take me up the Kilmore Gap to clear Melbourne control space, then head north-west to land at St Arnaud, followed by Echuca for another landing, finally coming back down south to return to my flying school. Looking at the area forecast on the day, there was nil significant weather until about 4 pm, when large cumulonimbus would be building. Not to worry, I should be home by 3 pm. Although much to my dislike, the mercury was tipped to reach 43 degrees at 2pm. Wow, what a stinker!

I departed at about 10:30 am and the first segment to St Arnaud was uneventful, albeit a bit hot and bumpy. After completing a few touch and goes, I departed overhead towards my next landing point at Echuca. It was at this time that I wished I had eaten more before I left, as my stomach was starting to give me grief. The hot and bumpy conditions only made things worse. Then I realised the aircraft was fitted with air conditioning, an aftermarket feature designed for a sick pilot like me, flying in 43-degree heat, who was in desperate need of some relief. I’d never used the air con before, but hey, how hard could it be? ‘High’ or ‘low’, ‘on’ or ‘off’? ‘I’ll take “high” and “on” please, Mr Cessna,’ I said to myself. Soon I was cool as a cucumber and happily on my way to Echuca.

It wasn’t long before I had forgotten about the aircon, as I focused my attention on preparing for my arrival at Echuca. I joined crosswind for runway 36 and started the before-landing checks. I had always been told to complete these checks without using the paper checklist, as eyes must stay outside in the circuit. As far as I was aware, the ‘A’ in BOUMFAH only stood for ‘autopilot disengaged’. I was soon to be proven very wrong.

As I descended on base, something felt different from normal. I couldn’t quite figure out what it was, so I checked all my engine gauges and instruments. Everything looked normal and I continued the approach. As I turned final, there was a large updraft of warm air that caused me to become high and fast on approach. In response to this, I reduced power to idle, extended full flap and held my aim point.

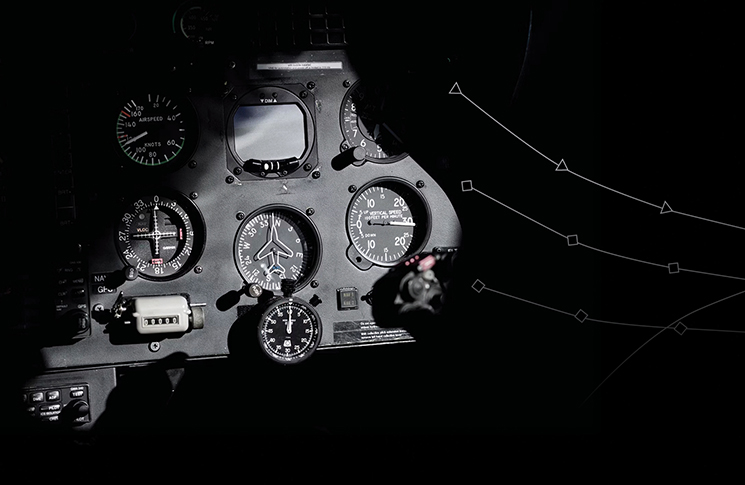

At about 400 feet, I glanced down at the tachometer and was surprised to see a reading of about 350 rpm. The normal reading is about 1500 rpm. A few seconds later, at what I think was about 300 feet, the engine and propeller stopped dead! I can’t recall exactly what happened after this point, but the next thing I can remember was touching down on the grass area just past the perimeter fence and rolling onto the sealed runway.

‘What had just happened,’ I thought. ‘Was that an engine failure? I think it was. What do I do now? Maybe you should try the engine failure checks? Yes, I’ll try that.’

I sat on the runway for about 2 minutes, trying to restart the engine. But every time I turned the magnetos to start positions, the propeller hardly moved. Then I realised there was something violently shaking the rudder pedals. ‘What could that be? Let’s get out and see what the heck is happening.’ As I climbed out, it became obvious that the violent shaking of the rudder pedals was actually my legs shivering as a result of shock. I pushed the aircraft about 200 metres to the nearest taxiway to clear the runway; this was extremely difficult with shaking legs and 43-degree heat. I figured I was in need of food and a drink. I got a taxi into town and had lunch.

Returning to the airport, I finally built up the courage to get back in the aircraft and try to figure out what was wrong. It wasn’t long before I realised that every time I turned on the master switch to try and start the engine, I could hear blaring fans from behind the glare shield, and feel air being blown onto my face. This explained the unusual feeling I had on base, and why I couldn’t start the engine on the ground. The aircon was still switched on.

As it turned out, the ‘A’ in the before-landing checklist was also marked as ‘Air conditioning—off/not applicable’, although this was not listed as a read back item, so I had never actually used it before. After finally starting up, I completed 3 sets of run-ups and, not finding any problems with the engine, taxied to the runway for my delayed return home.

On the way home, I entered the flight plan into the GPS and turned on the autopilot. I had had enough navigating for that day. Unfortunately, like a final curse from the gods of aviation, I encountered severe turbulence from building cumulonimbus on the way home. My late departure from Echuca had caused me to encounter the forecast storms developing on the way home. The result of this was my lunch making an unscheduled exit through my mouth just before landing back at home. Finally, I touched down; I had never been happier to be home.

On the following Monday, I submitted an incident report and discussed the events with the chief instructor. He believed the engine stoppage could have been caused by the air conditioning taking power away from the engine. As I had reduced power to idle on short final, the rpm had dropped to such a slow speed that the engine simply stopped. I believe that due to the conditions on the day, a very high-density altitude meant the engine’s power output was already significantly reduced. This, combined with low idle speed and the aircon belt taking power away from the crankshaft, was enough to cause engine failure.

Lessons learnt:

It haunts me to think what the outcome might have been had I been on a runway with trees on the approach or lost power just a few seconds earlier than had happened. Now I always check for air conditioning off before any landing and, more importantly, I give the checklists a lot more respect. I love my flying and hope to make it a safe career for myself. Hopefully, my story will cause others to learn from my mistake and maybe even save a life.

- This close call was first published in 2015.

Have you had a close call?

8 in 10 pilots say they learn best from other pilots and your narrow escape can be a valuable lesson.

We invite you to share your experience to help us improve aviation safety, whatever your role. You may be eligible for a free gift just for submitting your story.

Find out more and share your close call here.

I own a Cessna with what I assume to be a similar Kelly air-con system. It does take a few HP out of the engine which is why it must be turned off for takeoff and landing in case of go-around. However, I would be extremely doubtful it would cause engine and propellor stoppage at any stage of flight. It is unlikely the manufacturers would have secured a Supplemental Type Certificate for the modification if that was even a remote possibility. The pilot and presumably the flying school were unwise to fly that aircraft after such an engine stoppage. Something caused the engine stoppage but it was very unlikely it was the air-con if was working properly and maintained to the manufacturers specifications.