There’s an aviation hazard out there that doesn’t care how focused, diligent and talented a pilot you are. The more time you spend in the cockpit, the more likely you are to meet it and, as a pilot, you could be up to 42% more likely to encounter it than if you had taken your parents’ advice and studied law or medicine instead.

It’s skin cancer. If it can happen to someone like ‘Sully’ Sullenberger, the deservedly lauded pilot who successfully ditched an Airbus A320 in the Hudson River in New York in 2010, it can happen to you.

Skin cancer catch-up

It is long established that pilots and other aircrew have a higher rate of skin cancer than the general population. This is particularly concerning in Australia, which has:

- one of the world’s highest per capita rates of skin cancers

- the highest per capita rate of melanoma, the most serious type of skin cancer.

About 2 out of 3 Australians will be diagnosed with some form of skin cancer during their life. For the most serious type, melanoma, the incidence is 70 cases per 100,000, with men having a higher incidence than women. The death rate from skin cancer is 4.9 per 100,000, about the same as for road deaths.

Many factors can increase your risk of skin cancer.

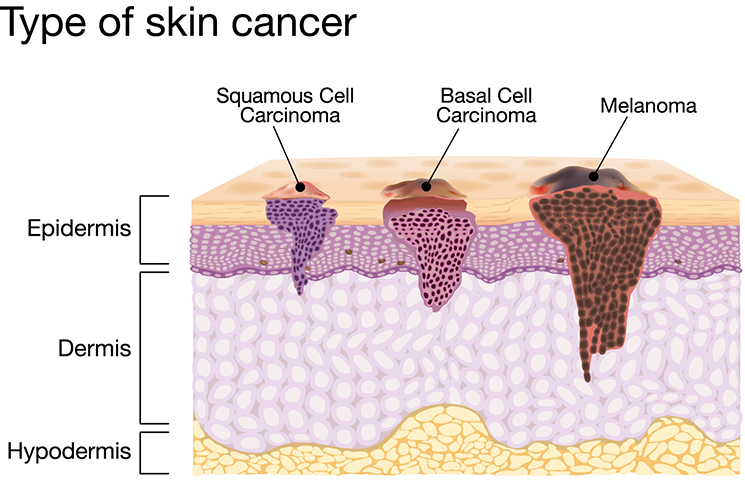

There are 3 main types of skin cancers:

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

- BCCs make up around 3 in every 4 skin cancers

- Presentation: can be varied and includes pink, pearl-like, flat or raised lump; or shiny, pale/bright/dark pink scaly area. May scab, weep or bleed

- Growth: slow over months or years. Established BCCs can be difficult to remove

- Occurrence: usually on head, face and limbs, but can occur anywhere.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

- Around 1/3 of skin cancer diagnoses

- Presentation: scaly lesion; a fast-growing pink lump; a red, scaly or crusted spot. May feel tender, inflamed, occasionally bleeds

- Growth: quickly over weeks or months, may metastasise into other areas of the body

- Occurrence: usually on sun-exposed head, face, ears, hands and limbs, but can occur anywhere.

Melanoma

- About 1 in 100 skin cancer diagnoses

- Presentation: asymmetric, with uneven or scalloped edges, differing shades and colours, and may bleed, itch or have a pink colour

- Growth: variable, from weeks to years, depending on subtype. Can metastasise quickly after period of slow growth

- Occurrence: anywhere; more common on head, face, limbs and sun-damaged skin.

Spot the imposters

Sunspots, moles and irregular moles are harmless but associated with increased likelihood of skin cancers developing. Age spots are harmless and not associated with increased skin cancer risk.

Only a medical skin specialist/dermatologist or doctor should determine what is or is not cancerous.

There are also various digital platforms that can be used as well, such as Skin Vision to help assess a spot, using a good photo and an algorithm for assessment.

Non-melanoma (keratinocyte) skin cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in Australia. Over one million treatments are given each year in Australia for non-melanoma skin cancers. BCC can develop in young people, but it is more common in people over 40. BCC occurs mostly in people over 50.

The aviation connection

There are several prime suspects for increased skin cancer rates among pilots.

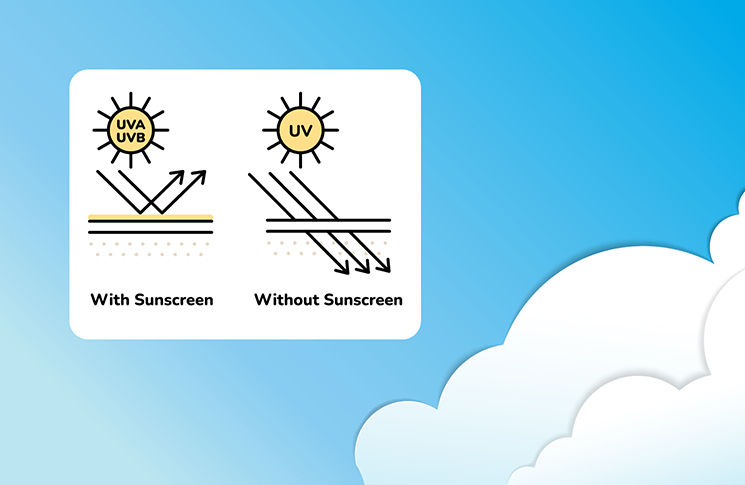

Ultraviolet radiation that causes sunburn and is associated with skin cancer increases by 10% for every 1,000 metre (3,370 foot) increase in altitude, placing aircrew at greater exposure. Ultraviolet radiation is categorised into two bands – UVA, which has a longer wavelength and is associated with deep layer skin damage, and UVB, which has a shorter wavelength and causes sunburn and damage on the outer skin layer. Unlike UVA, UVB can be blocked by glass.

Cosmic rays, sometimes called cosmic ionising radiation, are another suspect. These particles, moving at close to the speed of light, are produced by the sun and other stars. Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic fields protect its life forms from cosmic rays but this effect diminishes with altitude. Cosmic ray exposure increases significantly at more than about 30,000 feet and in flights over polar regions where the magnetic fields are thinnest.

The US National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements says aircrew have the largest average annual effective dose, 3.07 millisieverts (mSv), of all US radiation-exposed workers. (However, other estimates of annual aircrew cosmic radiation exposure vary widely, from 0.2 to 5 mSv per year.) In Australia each person receives an average dose of 1.5 mSv per year, according to the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency.

Solar flares, also called solar particle events, are another source of ionising radiation. The US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has estimated that pilots fly through about 6 solar particle events in an average 28-year career.

A 2015 study found a person flying for an hour at 30,000 feet is exposed to the same amount of UVA radiation as a 20-minute tanning bed session.

Scientific results

It is established that exposure to UV radiation and cosmic rays is associated with skin cancer risk to pilots and other aircrew.

A 2003 study of 10,000 Scandinavian airline pilots concluded, ‘This large study, based on reliable cancer incidence data, showed an increased incidence of skin cancer.’ It found the relative risk of skin cancers increased with the time since first employment, the number of flight hours and the estimated radiation dose.

A 2015 study found a person flying for an hour at 30,000 feet is exposed to the same amount of UVA radiation as a 20-minute tanning bed session.

A small 2016 study of glider pilots in Bavaria, southern Germany, concluded, ‘Our findings clearly suggest that glider pilots have a higher risk of keratinocyte carcinoma (non-melanoma skin cancer) compared with the general population’.

A 2019 meta-analysis of skin cancer studies among aviators concluded: ‘The available evidence shows that airline pilots and cabin crew have about twice the risk of melanoma and other skin cancers than the general population, with pilots more likely to die from melanoma.’

However, the study noted that most of the evidence it reviewed was collected several decades ago and ‘their relevance to contemporary levels of risk is uncertain’.

As for the specific effect of cosmic rays, a 2022 study looking at long-haul flight and cabin crew said, ‘There is evidence of a [cosmic ray] dose-response relationship for melanoma, however, this pattern has yet to be fully disentangled from the impact of circadian rhythm disruption.’

Countermeasures

Several of the studies mentioned that the lifestyle of pilots and cabin crew may be a confounding factor. Specifically, many pilots also engaged in outdoor recreations, and international airline crews spent a significant number of days per year in hot and sunny locations, often relaxing or exploring for part of the time. All these activities could increase UV exposure over the general population.

One study concluded, ‘The skin melanoma excess reflects sunrelated behaviour rather than cosmic radiation exposure.’ From a practical point of view, this makes little difference – the countermeasures are the same and well known.

Pilots and crew can take several steps to protect themselves from UV radiation:

- Slip on some sun-protective clothing that covers as much skin as possible.

- Slop on SPF50 or SPF50+, broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen. Put it on 20 minutes before you go outdoors and every 2 hours afterwards. Sunscreen should never be used to extend the time you spend in the sun.

- Slap on a hat, broad brim or legionnaire style, to protect your face, head, neck and ears.

- Seek shade.

- Slide on some sunglasses – make sure they meet Australian Standards. Their tint and polarisation need to be approved by an optometrist or ophthalmologist for use in

aviation. - See a skin cancer specialist or dermatologist at least once a year – depending on results, checks may be extended to 2-year intervals.

You can also protect yourself by installing UV-blocking films on your aircraft’s windows. And recently, skin cancer detection apps, such as Skin Vision, which uses your mobile phone’s camera and artificial intelligence software to detect and analyse moles and marks, have shown promise. These are subscriber services that send you a message following review, for doctor or dermatologist review if they detect suspicious looking skin flaws. At their current development these services are an addition, but not a substitute, for regular checks by a professional; for one thing, taking a selfie of your back is hard!

By incorporating these measures, pilots and flight crew can significantly reduce their risk of UV-related skin issues.

Captain Sullenberger received a wave of support and sympathy after sharing an image of his bandaged head online. ‘It’s true, all those hours in the cockpit add up,’ he wrote, ‘Early diagnosis is key, get your skin checked! And a scar might add a little character’.

Early diagnosis is key, get your skin checked!

Risk factors

Many factors can increase your risk of skin cancer, including having:

- pale or freckled skin, especially if it burns easily and doesn’t tan

- red or fair hair and light-coloured eyes (blue or green)

- unprotected exposure to UV radiation, particularly a pattern of short, intense periods of sun exposure and sunburn, such as on weekends and holidays

- actively tanned, sunbaked or used solariums

- worked outdoors or spent a lot of time outside (e.g. gardening or golfing)

- been exposed to arsenic

- a weakened immune system– this may be from having leukaemia or lymphoma or using medicines that suppress the immune system (e.g. for rheumatoid arthritis, another autoimmune disease or an organ transplant)

- lots of moles, or lots of moles with an irregular shape and uneven colour

- a previous skin cancer or a family history of skin cancer

- certain skin conditions such as sunspots, because they show that you have had a lot

of skin damage from exposure to the sun - smoked cigarettes, as smoking has been linked to a possible increase in skin cancer risk.

People with brown, black, olive or very dark skin colour often have more protection against UV radiation because their skin produces more melanin than fair skin does. However, they can still develop skin cancer.

Source: Cancer Council NSW