A new colour vision assessment will allow more pilots to fly safely

Luke Zaccaria grew up dreaming of a career flying high above the clouds.

Since he was young, Luke had a clear vision of what he wanted to do in life and that was flying for an international airline.

Over the years, Luke’s passion for aviation flourished. He joined the Air Force cadets where he learnt the basics of flying, got to fly gliders, and eventually gained his Gliding Federation of Australia C certificate.

As his skills and experience grew, Luke moved from challenge to challenge. He worked hard and was eventually accepted into the Qantas Group Pilot Academy in Toowoomba.

He was over the moon, but there was something that caused constant worry for him.

Luke always knew he was colour vision deficient (CVD) – specifically deficient in perceiving the colour green (known as deuteranopia).

Luke had been able to acquire his aviation medical to fly gliders. However, flying powered aircraft to obtain his commercial pilot licence (CPL) and air transport pilot licence (ATPL) was another story.

Due to his colour vision deficiency, there was always a real risk Luke’s medical certificate would have conditions placed on it relating to the types of flying he could pursue. And one day, that reality eventuated. It threw a spanner into the works of his plans. He wouldn’t be able to pursue his lifelong ambitions.

‘I was absolutely devastated,’ he says.

‘My whole career ambition was to fly for the airlines – I didn’t have a plan B! The uncertainty of not knowing if I could achieve all the things I wanted to achieve was such a confronting and scary thought’.

Colour vision and the aviation industry

Historically, pilots diagnosed with congenital colour vision deficiencies have had restrictions placed on their medical certificates, limiting their flying, depending on the severity of the condition. (But the good news is, that has changed).

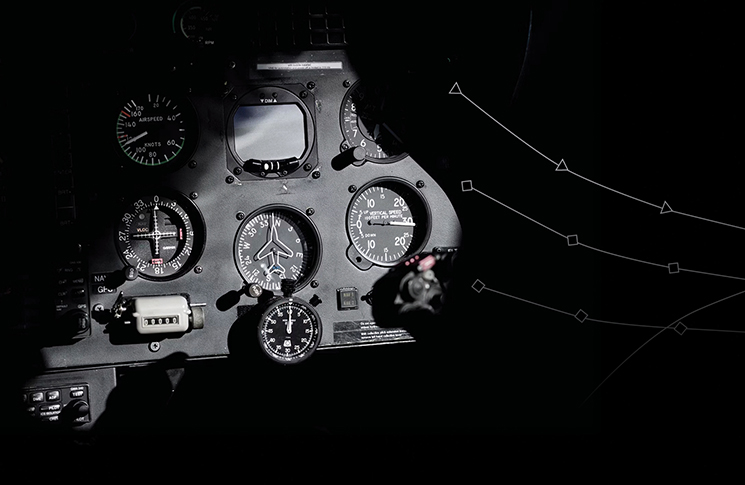

These restrictions typically included rules limiting the size and type of aircraft, and night flying.

Much like traffic lights, aerodromes use coloured lights to indicate to pilots if it is safe to perform certain actions. For example, precision approach path indicator (PAPI) lights are installed at many airports and indicate whether a pilot is flying the aircraft on the correct slope. Runways also have coloured lights at the threshold and touchdown points.

Over the past half century, the prevailing thinking was pilots were required to have perfect colour vision. The terms ‘colour blindness’ or ‘colour vision deficiency’ became highly stigmatised, as well as being perceived as a threat to the safe operation of an aircraft.

However, as new research was conducted, new methods for colour vision testing were developed and gradually, different countries began changing their approach to colour vision testing, to consider the operational risks that such a condition introduced and how they could be managed.

These studies determined having a colour vision deficiency was not necessarily always a risk to the safety of the pilot, passengers or aircraft, provided an applicant can pass a prescribed operational test. However, it also acknowledged that severe colour vision deficiency may require additional consideration of the risks and operating environment.

National aviation authorities that have adopted this approach include the United States, New Zealand and South Africa.

CASA reviews its policy

In Australia, CASA began exploring ways to acquire a medical certificate while managing any potential operational risks.

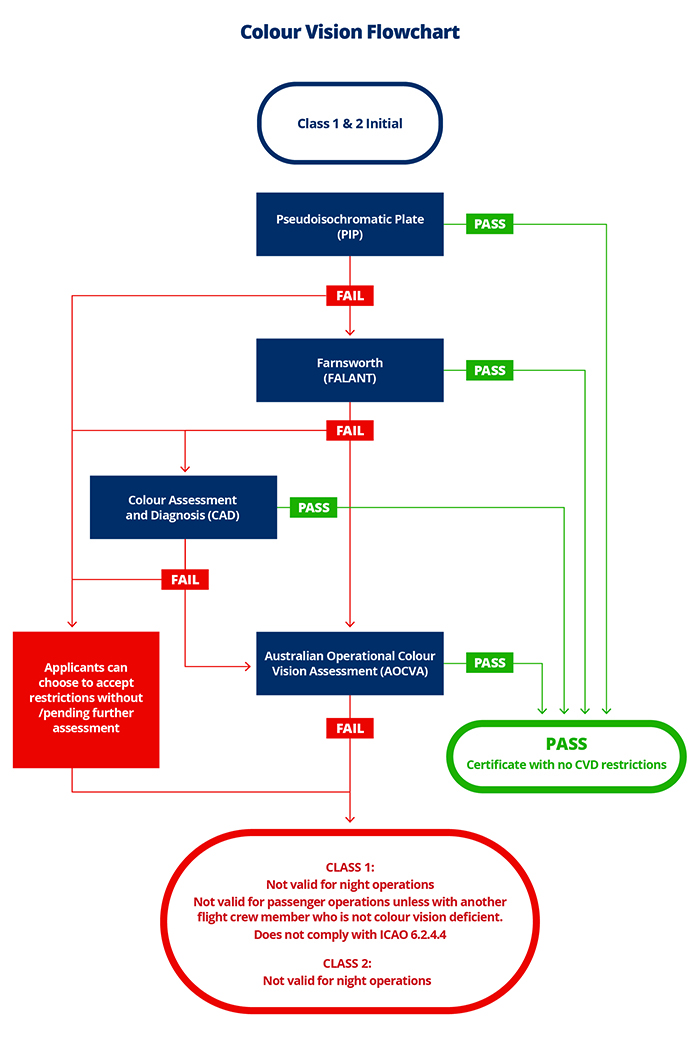

Last month it introduced the Australian Operational Colour Vision Assessment (AOCVA), an operational examination to test applicants in 3 practical components which imitate a scenario that would allow pilots to demonstrate they can fly safely in all kinds of circumstances, particularly safety critical ones, such as:

- A ground component that tests pilots on their ability to read aeronautical charts, flight instruments and displays

- A flight component that tests pilots on their ability to interpret precision approach path indicator (PAPI) lights in day conditions

- A second flight component that tests pilots on their ability to recognise and interpret aerodrome lights, aircraft lights and other colour-based aeronautical signals in day and night conditions.

If a pilot passes all components, they are issued a Class 1 or Class 2 medical certificate, with no colour vision restrictions.

CASA’s Principal Medical Officer Dr Kate Manderson says, ‘the new examination standardises operational colour vision testing and provides greater opportunity for prospective pilots to get into the industry.

‘The AOCVA operational assessment is beneficial for colour vision deficient pilots as it provides them with a genuine pathway to receiving a clean medical certificate, where they have demonstrated that they can do so safely.’

Change of policy welcome

Allowing colour vision deficient pilots the opportunity to demonstrate their abilities in an operational test has been a goal of John O’Brien’s for many years.

John is the co-director of the Colour Vision Defective Pilot’s Association (CVDPA), a body that advocates and promotes the rights of existing and aspiring pilots to get into the aviation industry.

As John is colour vision deficient himself, he knows firsthand the challenges aspiring pilots face during their medical examinations. With over 22 years in the industry and over 10,000 flight hours, John is an experienced airline pilot, having flown Dash 8, A320, and currently B747 aircraft. He is also a qualified flight examiner and instructor and was a member of the CASA Technical Working Group (TWG) that provided industry insight and helped develop a pathway forward for CVD pilots.

‘Due to the stigma around what being colour vision deficient means within the aviation industry, when a prospective pilot is diagnosed as CVD, it can be a soul-crushing experience, and can wreak havoc on their mental health,’ he says.

‘Thankfully, after many years of advocacy, CASA has improved their policy and reintroduced a standardised operational test that offers fair opportunity for CVD pilots.

‘For too long, clinical eye examinations have been used to preclude people from pursuing a career as a pilot. This is why having an operational test is so important – so pilots can demonstrate their proficiency practically to operate an aircraft in the same way as non-CVD pilots.’

John says that even though the new policy has been implemented, there is still work to do to eliminate the stigma around colour vision across aviation industry.

‘As strange as it sounds these days, once upon a time, female pilots couldn’t become airline pilots due to archaic assumptions. That was until a landmark legal victory finally allowed them to,’ he says. ‘Over time, women proved they could perform the job safely in the same manner as men doing the same role.

‘The same thing needs to happen with colour vision pilots.’

‘It is incumbent upon all of us to educate and inform industry that having a colour vision deficiency isn’t a career-stopping condition, and that pilots who have it can operate and fly aircraft safely.’

Onwards and upwards

Luke recently passed the operational test at Toowoomba Wellcamp airport.

‘I was a bit nervous before the test began but at the end of the day, you just need to treat it like any other flight,’ he says.

‘You can’t necessarily control how an examination will go, but you can control your preparation for it. As long as you are prepared, you will be fine.’

This is only just the beginning of Luke’s journey. In the immediate term he plans to pursue working for a turboprop operation. Longer term, he plans to gain an aerobatic rating, become a gliding instructor for the Air Force cadets to give back to the organisation that provided him his start in the industry, and has his eyes set on working for Qantas mainline.

Asked if he recommends fellow pilots who have a colour vision deficiency take the new test, Luke says it’s worth it.

‘Do it, because the sky’s the limit!’

Further information

For more information, visit CASA’s Colour vision assessment for medical certificates webpage.

This was very helpful. Thanks!