Detection technology is your best defence against this sly subtle menace

The temperature has well and truly dropped in many parts of the country. Clear, crisp and frosty mornings dominate the landscape. Depending on where you live, you might be spending 10 minutes or so scraping the ice off the windscreen of your car – or aircraft.

Winter is an excellent time for flying, with cooler days providing ideal flying conditions. Pilots often experience better aircraft performance in cold weather.

Cooler air is denser than warmer air, which contributes to better engine performance, climb rate and take-off distance.

Despite its advantages, winter flying can also present challenges. One is the increased risk of carbon monoxide (CO) exposure from internal cabin heating, particularly if the heating ducts and climate control system haven’t been used for some time. Cracks might have formed during this time, compromising their integrity.

Like with anything sitting idly for long periods of time, as soon as you start using them again, they can initially be a bit shaky. Think an old car that hasn’t been turned on for a while, and even your jelly legs when you get up from your seat after a long-haul flight.

The heating components in a light piston engine aircraft are no different.

As an aircraft climbs, the outside air temperate drops by 2° C for every 1,000 feet gained so the pilot may turn on the heater.

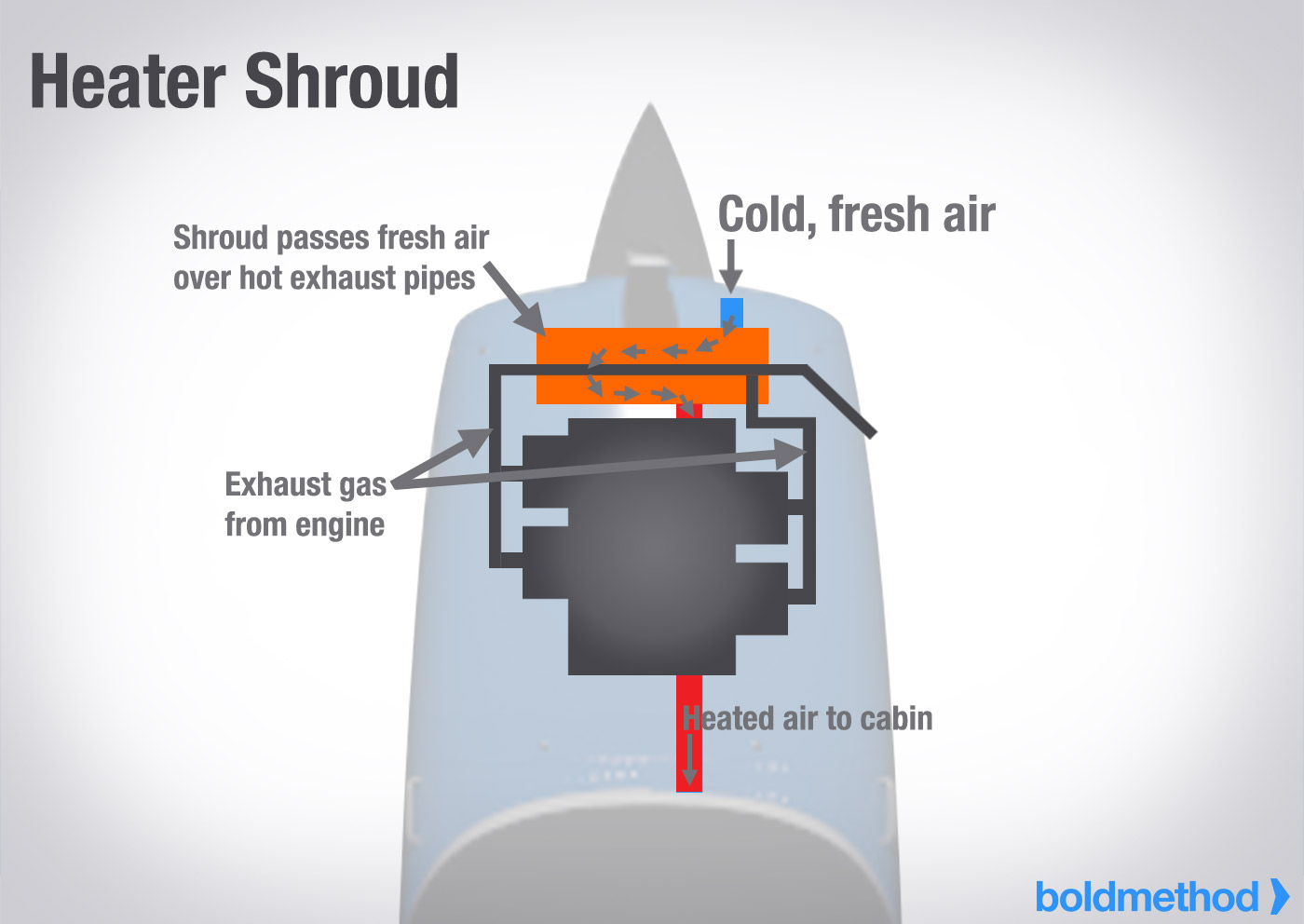

In most single-engine piston aircraft, heat to warm the cabin is generated when air enters the heating shroud. The air is heated when it passes over hot exhaust pipes, then it is directed through the ducts and into the cabin.

However, there is danger if cracks or abrasions have formed on the muffler since heating system was last used. Even a slight crack can cause engine exhaust to mix with the fresh air, allowing CO to enter the cabin.

Low-level exposure to this gas can cause headaches, nausea, dizziness and drowsiness. High-level exposure can cause shortness of breath, blurred vision, confusion, unconsciousness and even death – if not from the CO itself, then from the aircraft crashing.

To avoid long-term exposure to CO, it is important all piston engine aircraft – but especially single-engine piston aircraft, where the engine sits directly in front of you – are fitted with an active (electronic) CO detector. They can sense the presence of CO even at the lowest levels, giving the pilot time to land the aircraft safely before the effects of the poisonous gas take hold.

Even if there is already a detector fitted, pilots are encouraged to carry a portable unit as well. There is no such thing as having too many fail-safes!

Double your safety

Safety manager and pilot with Flinders Island Aviation Jaime Taylor has many hours experience flying in cold weather frequently experienced in Tasmania, and recently participated in an AvSafety webinar run by CASA about flying in winter conditions.

‘Here in Tasmania, we experience colder conditions than much of the rest of the country,’ he says. ‘Usually, our winter flying can last from March until September of any given year.

‘One of the most critical things to remember about winter flying is the need to use carbon monoxide detectors in the aircraft.’

Taylor says it is essential that pilots who intend to fly in winter conditions are aware of the dangers, and recommends using two carbon detectors, for redundancy.

‘I buy a redundancy detector every year, just in case… And there is no better time than the start of winter!’

Top tips if CO is detected in the cabin

But what happens if your active detector does pick up the presence of CO? Here are some tips for what you should do if your detector goes off during flight.

- Turn off the heat coming into the cabin

Carbon monoxide gas is streaming in from over the engines, pumping out exhaust fumes. Closing the heating valves will slow down this process.

- Open the aircraft’s fresh air vents and cabin windows

Allowing fresh air to flow into the cabin will dissipate any build-up of CO gas.

- Inform air traffic control

It is vital you tell ATC about your situation so they can prioritise your landing and potentially arrange for medical services when you land.

- Land the aircraft as soon as possible

Head for the nearest airfield. The debilitating effects of CO exposure can take hold extremely quickly, so it is important you make landing a priority. If there are no airfields in the vicinity, look for an empty paddock to set down.

- Get urgent medical attention

Even if you feel fine, you still could have been exposed to high levels of CO. Call for medical assistance as soon as you land. If at an airfield, ATC can arrange this. If you are in a remote area, call for assistance using your mobile phone or your radio.

Remember, if you’ve been exposed to carbon monoxide, you can’t just necessarily ‘walk it off’. There could be some underlying symptoms that could affect your cognition later.

Further information

For more information about CO detectors and other things to look out for when flying during winter, watch our latest AvSafety webinar.

Visit the Pilot safety hub for all the latest on controlled aerodromes and operations.

Useful links

- Carbon monoxide poisoning fact sheet | Civil Aviation Safety Authority (casa.gov.au)

- Carbon monoxide poisoning case study | Civil Aviation Safety Authority (casa.gov.au)

- Airworthiness Bulletin – Carbon monoxide

- Tackling a toolbox talk with maintenance engineers – carbon monoxide | Flight Safety Australia