In aviation, as in life, separation is preferable to conflict. Nowhere is this more true than in IFR operations.

Of all the components when learning to fly, the instrument rating syllabus is arguably one of the biggest challenges. Understandably, the focus of the rating is often on the more tangible parts of flying under the IFR. Flying an ILS or RNAV, managing engine failures, handling missed approaches – all are key elements of becoming a proficient instrument pilot.

One of the less considered challenges of IFR flying is managing traffic, particularly around non-controlled aerodromes. For the most part, ATC assists with en route separation and handles flow of traffic into the controlled aerodromes around our major centres. But when we descend into and depart from aerodromes in Class G airspace, the responsibility for separation is with the pilot.

Mildura, Wagga Wagga, West Wellcamp, Ballina and Proserpine are some of Australia’s busiest uncontrolled airports. Multiple simultaneous air transport arrivals, sometimes with a mix of regional turboprops and narrow-body jets, are difficult enough. But when you overlay on this the training aircraft, charter and other local operators, building the picture becomes the first big challenge.

Start by writing it down

For IFR aircraft, building the picture of the airspace around you for a departure or arrival often starts with the IFR traffic statement. This is the advice provided by ATC to an IFR aircraft prior to entering Class G airspace, of any known IFR traffic in the vicinity. It is often passed at the same time as information about any known VFR traffic, sometimes identified from ADS-B transponder returns.

The IFR traffic statement can contain a lot of information in a very short period. It’s often paired with a descent clearance, a QNH or a frequency handover. The easiest way to get on top of all of this is simple – write it down. I prefer pen and paper, going directly into a blank area on my navigation log, but other pilots I’ve flown with make the scratchpad on their EFB work well for this purpose. In either case, be ready to write. Most of the time, all you need to write is the callsign and ETA or ETD for any other aircraft.

How far apart?

A common unknown for newer IFR pilots is exactly how much separation is required in Class G airspace when you can’t visually separate.

In controlled airspace, air traffic controllers have a defined separation standard – the minimum lateral and vertical distances permitted between aircraft. Controllers have a more than 600-page manual that defines this standard – the Manual of Air Traffic Services (MATS).

In VMC in both controlled and uncontrolled airspace, visual separation between conflicting aircraft may be perfectly acceptable. Sight the other aircraft and visually separate – this is the ‘common sense’ separation we typically apply at uncontrolled aerodromes. When one or both aircraft are in IMC, things get a little cloudier.

The MATS states that aircraft in controlled airspace that are not able to see each other must have either lateral or vertical separation (or both). The manual explains at length how separation should occur in various situations; however, for en route operations in RNP2-capable GNSS-equipped aircraft (most IFR operations), acceptable separation boils down to either:

- 1,000-feet vertical separation

- 5-nm lateral (horizontal) separation.

But of course, the MATS exists for air traffic controllers, not pilots. The AIP and the regulations are less-prescriptive on the topic of separation in Class G, other than to say it’s probably a good idea, which leaves it up to the pilot to come up with a safe plan based on the circumstances. So why bring up the MATS at all? Well, it offers something to base our decision-making on – a basic standard which pilots can use, even at uncontrolled aerodromes.

In summary, if you can’t sight another aircraft for visual separation, aim for a minimum of 1,000-feet vertical separation and 5-nm lateral separation. Aim for a minimum of 2 minutes separation between position ETAs, such as approach waypoints.

Putting separation into practice

Like many things in flying, it’s all easy enough until you have to do it! I’ve sat next to many a pilot under supervision as they’re faced with, perhaps, their first IFR traffic separation puzzle at a busy uncontrolled airport. They receive all the information, understand what separation is required, but haven’t ever had to think about how to pull it all together.

A common unknown for newer IFR pilots is exactly how much separation is required in Class G airspace when you can’t visually separate.

I give pilots new to IFR operations 3 steps to manage this – plan, negotiate, review:

- plan how you will separate from the other aircraft

- negotiate that plan with the other aircraft affected

- review the plan as it unfolds and take action if separation breaks down.

Planning separation

Planning separation is complex and every situation you come across will be different in subtle ways. Here I will focus on departure/arrival conflicts, i.e. one IFR aircraft departing into IMC, one arriving in IMC. This scenario is arguably the most common and the highest risk.

The principles apply equally when you have additional aircraft or must manage multiple conflicting arrivals or concurrent departures. The goal in your plan is to systemically protect your separation of 1,000 feet vertically or 5 nm laterally.

Here are 3 examples of how you could plan separation for an inbound and an outbound aircraft in Class G airspace.

Example 1: Differing tracks, lateral separation

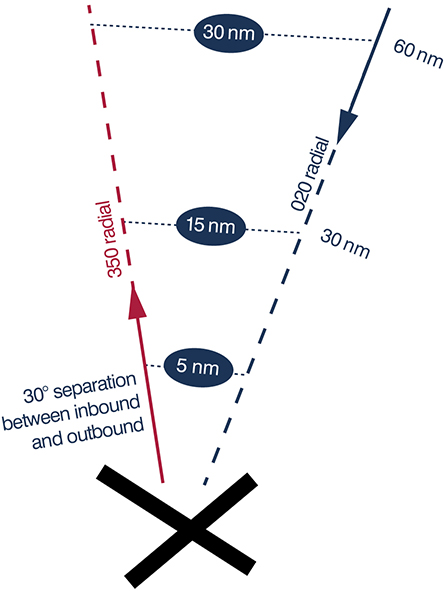

You are departing on the 350 radial. You have been advised that another aircraft is inbound on the 020 radial and is due to arrive at the field 7 minutes after your departure time. Diagram 1 depicts this, overlaid with the lateral separation as you move further from the aerodrome.

Sidenote: how do you work out the distances? Contrary to popular belief, the 1-in-60 rule isn’t just for VFR pilots. With 30 degrees of radial separation, at a distance of 60 nm, the radials are 30 nm laterally separated, meaning that our 5 nm of lateral separation is achieved 10 nm from the field.

The plan that this converts to is – the outbound aircraft will plan to pass 10 nm from the field before the other aircraft gets to 10 nm. Therefore, as long as both aircraft are not concurrently within 10 nm of the field, lateral separation is ensured.

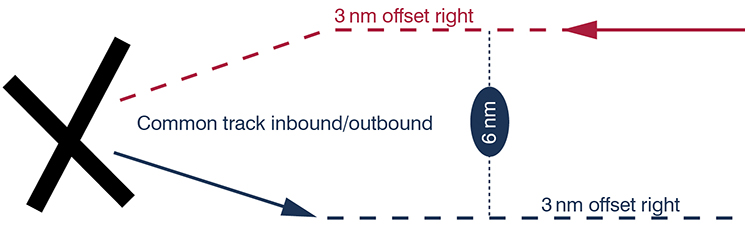

Example 2: Reciprocal tracks, lateral separation

Now consider that the inbound aircraft is on our reciprocal track. Vertical separation may not be desired, so you may plan to separate by each deviating 3 nm right of route, thereby ensuring at least 5 nm between the aircraft.

Example 3: Reciprocal tracks, vertical separation

As in Example 2, reciprocal tracks generate a conflict; however, this time vertical separation is planned. The departing aircraft will level off at A040 and the arriving aircraft at A050. Once it is confirmed the aircraft have passed one another (ensuring lateral separation), each may continue unrestricted climb or descent.

Negotiate your plan

The AIP goes to great pains to explain that under no circumstances should one aircraft direct another aircraft. And so, the key here is that you negotiate your plan for separation with the other aircraft.

This negotiation should normally occur on CTAF, although there may be times where the area frequency or even interpilot, 123.45 MHz, is the appropriate channels to have this conversation.

Importantly, although the area controller may pass you traffic information and may want to know you have a plan for separating, they will not tell you how to separate in Class G airspace. That’s entirely up to you and the other pilot. The area controller will likely still pay attention, so telling them you’ve got a plan for separation isn’t a terrible idea.

There is no standard phraseology for negotiating separation in Class G – plain language is the way to go. Address the other aircraft directly using their callsign (which is why it’s important to write their callsign down). Once you’ve established contact, in as simple terms as you can, explain the plan you have in your head for ensuring separation, and ask if they’d like to be a part of that plan. The other crew might have other ideas but, between the (at least) 2 of you, come up with something mutually acceptable.

The time to have this negotiation will depend on where the potential conflict is; if you’re going to pass each other 40 nm from the field, it’s likely to be something you talk about after departure. But, especially for single-pilot operators, planning separation is a hell of a lot easier on the ground – not when flying an aircraft in IMC.

Review the plan as it unfolds

Once you’ve got your plan for separation in place, negotiated and running, keep reviewing it. They say no plan survives contact with the enemy and half the time, you’ll find that your separation plan either goes out the window or becomes completely unnecessary.

Maybe the inbound aircraft breaks off from the reciprocal track to head to an initial approach fix for an instrument approach. Perhaps the outbound aircraft delays their departure by 3 minutes due to a VFR aircraft backtracking on the runway.

Importantly, if your plan isn’t working and you can’t ensure an acceptable level of separation, you have to act. Pilots shouldn’t be afraid to deviate from track or level off, to re-establish separation, especially in Class G airspace.

These situations can be incredibly dynamic. Closing speeds for reciprocal aircraft can be upwards of 400 knots – 6 or more miles a minute. If situational awareness is lost, the best thing you can offer the other aircraft is information about what you are doing – position and altitude, along with your intentions.

Fundamentally, you can never assume separation exists in uncontrolled airspace. Area controllers won’t instruct you on how to separate in Class G. It is up to IFR pilots to create and ensure separation. Plan how you will do this, negotiate it with the other airspace users around you and monitor and review separation continually, until you reach the sanctity of controlled airspace above you.

If your plan isn’t working and you can’t ensure an acceptable level of separation, you have to act.

Non-controlled operations is one of the special topics on our Pilot safety hub. Refresh your knowledge.

See and be seen with ADS-B

Automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast (ADS-B) helps improve situational awareness of pilots. It also allows air traffic control to see you and other aircraft, helping to improve safety.