The contributing factors involved in general aviation accidents are no mystery, but avoiding them requires effort and discipline.

I’ve been an active flight instructor for 36 years and, for most of that time, have been creating lessons based on accident data. In that time, I’ve learnt a few things about flying’s risks and its rewards.

The key lesson on risks is:

The causes of almost all accidents are very predictable. We’re doing the same things again and again. The good news is this means most accidents are preventable, but only if we heed the lessons learnt from the unfortunate experiences of others.

This knowledge leads to some suggestions on how to avoid a majority of aircraft accidents: by planning to evade the common causes. Some of my suggestions may sound overly conservative. But I bet the pilots who crashed thought they could get away with it too.

First, some general tenets

Know what the aeroplane is – and isn’t

The one you’re flying may have extraordinary avionics and equipment, but it is not an airliner. It is a recreational vehicle, personal transportation or perhaps a business tool. It has not been designed, tested, certificated or maintained to the same level as an air transport aircraft. It doesn’t have the performance, redundancy or support of an airliner. It is very safe and very capable – if flown within its limitations.

Know what you are – and aren’t

You are probably not a military, corporate jet or air transport pilot. Even if you are, or have been at one time, that experience does not fully prepare you for the workload of single-pilot operations. Fly to your experience in type, not to what you’ve done in a different aircraft, in a completely different environment.

Evaluate and monitor the weather

By far the most common reason for airline delays is adverse weather. Your aeroplane is less capable to handle adverse weather than an air transport aircraft. Consequently, you will need to delay, divert or cancel flights even more frequently than the airlines. The more you fly, the more you’ll delay, reroute or cancel because of the weather.

If you do not set the schedule for events that create the need for your trip, or if there are repercussions or lost revenue if for delays or cancellations, then plan to depart in time to delay, divert or cancel and still make it to your commitment by other means if necessary. This is especially true for the trip back home, when you often have personal pressure to arrive on schedule. This sometimes means traveling a day earlier, or cutting your trip short if forecasts show the weather may close in.

Two hundred hours of flying from point A to point B alone probably won’t protect you if a fuel pump dies close to the ground.

You are pilot-in-command, the captain of your aircraft

You are also dispatcher and director of maintenance. You are responsible for self-certification of your fitness to fly, before and during flight. You are the chief pilot, questioning and evaluating your own performance. Plan each flight consciously thinking about the responsibility of all these roles. In general aviation, ‘If it’s to do, it’s up to you.’

Based on actual events

Create and follow a personal training plan

A brief flight review for aircraft and operational ratings every 2 years is probably sufficient for most pilots of simple, VFR-only aeroplanes. But it’s not nearly enough for everything the cross-country pilot, the instrument pilot or the pilot of a complex or high-performance aircraft must be prepared for. Teaching multi-engine aircraft pilots at a simulator training facility convinced me biennial training alone is insufficient – it often took all our time simply to get back to meeting minimum standards. Pilots who trained twice a year tended to meet the minimum standards and went on to improve over time.

Flying time does not by itself replace the need to train

It doesn’t for professional pilots, so why should it for you? Two hundred hours of flying from point A to point B alone probably won’t protect you if a fuel pump dies close to the ground, or if you encounter unforecast low-level wind shear. Two hours of solid practice or challenging instruction 2 or 3 times a year is probably the better measure of a prepared pilot.

Plan to fly slowly more often

Loss of control inflight (LOC-I) is the cause of more than 40% of fatal general aviation accidents in the approach and landing phase of flight. In most cases LOC-I is a euphemism for stall. Many pilots are not comfortable flying at the slow end of the aircraft’s flight envelope, where you are on take-off and go around, and where you need to be during landing. Discomfort is a symptom of undeveloped or atrophied skill.

Regularly hand fly the aircraft

Fatal crashes often result from a pilot’s inability to manually fly the aircraft in the event of an autopilot disconnect or failure. Often pilots lose control almost immediately upon a trim runaway or autopilot disconnect – the moment when they must instantly transition from automated flight to hand flying, with an aircraft that is radically out of trim as a result of the failure mode. Practise hand flying, to be as capable at that as you are using an autopilot.

Maintain mode awareness

The corollary to hand flying is to be adept at the operation of your avionics and autopilot, so there’s never any doubt about the mode in which it’s operating or what the equipment is going to do next.

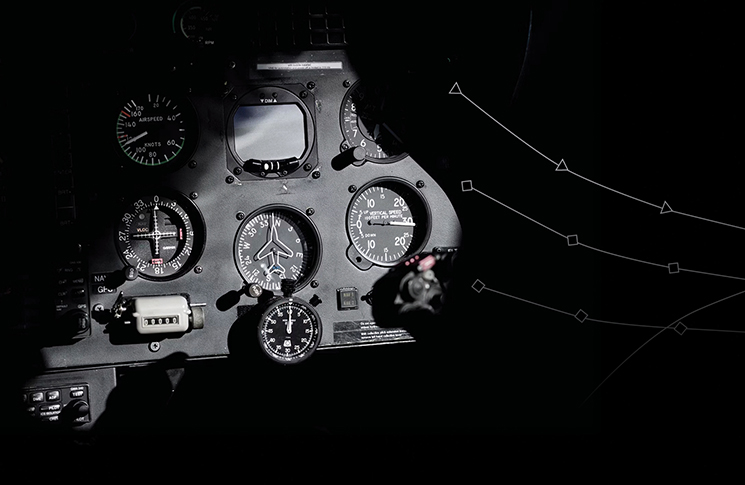

Plan for instrument failure

Half an hour of partial panel flying every 6 months may be worth more than a panel full of backup instruments. The hard part is identification of a partial panel situation in the first place. Besides actual failure, the only way to experience this realistically is in a flight training device or simulator. Seek out today’s accessible simulation to plan for the worst.

Half an hour of partial panel flying every 6 months may be worth more than a panel full of backup instruments.

Maintain situational awareness

The record suggests a decline in controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) events that coincides with the widespread availability of cockpit moving map displays. That said, CFIT continues to be a problem. Whether VFR or IFR, always know the lowest safe altitude for your current and next segment of flight.

Know your EPs – emergency procedures

Why are air transport operations so safe? In a large part, it’s because the crews are required to perform normal and EPs in simulated scenarios every 6 months. When an actual abnormality or emergency arises (almost never ‘textbook’ as presented in the simulator), pilots have a wealth of experience to analyse the situation. If you haven’t been practising and reviewing EPs regularly, you’ve not planned for the day an emergency occurs.

Plan your fuel and fly your plan

Far too many pilots have died trying to make it home because that’s where the cheaper fuel was, or stretched the aeroplane’s range to avoid the inconvenience of a stop. When one tank is down to 1/8 full and the other is at 1/4, it’s time to be inbound to the circuit. History shows many fuel exhaustion mishaps happen within 5 nautical miles of the planned destination – the pilot thought they could make it – and almost did. Fill up based on fuel need, not fuel price, carefully manage and monitor your fuel inflight and be willing to land for more if there’s any doubt.

Calculating aircraft weight and balance isn’t a training exercise reserved for checkrides and flight reviews. Plan to load your aeroplane within its control and performance flight envelope. An overweight aircraft, or one loaded near or beyond its design capability, will be harder to control under abnormal situations and perform less well when density altitude and wind adversely affect it.

Fly at the lowest weight that meets the trip requirements, with a generous fuel reserve – the lighter the aeroplane, the better it will perform and the more options you’ll have in an emergency. The availability of computer- and app-based weight-and-balance calculators make it easy to be sure.

Plan to stay within limitations

This means the aircraft’s limitations – there’s no such thing as a ‘little overweight’ or a ‘little over redline’. It means weather limitations – no flying through ‘a little thunderstorm’ or ‘a trace of ice’ or flying ‘a little lower’ on approach. It means your limitations – certificates, ratings and currency. If you cheat, human nature suggests it’s likely you’ll soon be accepting more and more risk as ‘normalisation of deviance’ sets in. What was once unacceptable has gradually become your norm. It means the mechanical limitations – follow the rules about required equipment and inoperative equipment. Regulations are minimum standard, the very edge of appropriately managed risk. Where limitations are concerned, ‘No means no.’

Standard operating procedures (SOPs) are the normal way you do things. Strive to fly as close to the same way every time. This avoids the need for too many in-flight decisions (not to eliminate the decision-making process entirely, but to make decisions ahead of time) and permits you to more easily detect and act upon variables like wind, traffic, equipment issues and other factors; you’re not so busy with the basics of flying that you have no mental bandwidth for external stress.

Using SOPs has another advantage – if you need to do something different from your SOP, you’ll have a yardstick of what ‘good’ is and be able to judge what you’re actually doing compared to your expectations and needs.

Plan stabilised approaches

Airspeed, power and aeroplane configuration not conforming to SOPs for final approach, commonly correlates to aircraft accidents. On final approach, ask yourself if the aeroplane is:

- on speed (Vref +5 knots -0 knots)

- at the proper rate of descent (usually 500 to 750 feet per minute, except in an obstacle landing)

- on target (following the glide path to land on the touchdown markers or in the first third of the runway, whichever is shorter)

- in configuration (flaps and gear set correctly, power and attitude as expected).

If the answer to any of these is ‘no’ within 500 feet of the ground, go around.

Unlike air transport operations, with maximum duty days and mandated rest periods and time off, nothing stands between the pilot in command and their judgment of their level of fatigue. If you’re a morning person, don’t fly after work. If you dance or work the night away, don’t plan on an 0600 departure. A Friday evening trip after a long work week, or a Sunday afternoon flight home after a whirlwind holiday, is setting yourself up for bad decision-making – a factor in as much as 80% of all general aviation crashes.

Even more challenging: evaluate not only how you feel for departure but predict how you’re likely to perform 3 or 4 hours later after bouncing around in turbulence, then faced with a missed approach or abnormal emergency condition.

Involve your family and passengers in your planning

Show them what you’re planning so you can make informed decisions and appropriately manage risk. Ask them to concur with your go/no-go decision and give them the power to cancel, delay or divert en route if they feel uncomfortable. Often, it’s real or perceived pressure from family or passengers that leads a pilot to accept an unacceptable level of risk, because non-pilots have no idea what conditions you require to safely complete a flight. If those around you have some basic understanding of what is acceptable and what is not, you may find you’re under far less pressure to ‘go’.

Sometimes, things break

The failure may not be complete, but the status and reduced capability will demand more of the pilot’s attention, making it harder to manage risk in other areas. Pilots and aeroplane owners tend to interchange the words ‘maintenance’ and ‘repair’ but there is a vital distinction. Maintenance is what you do routinely, before something fails, to maintain airworthiness. Once it breaks you need repair. It may be safe (appropriately managed risk) to defer some maintenance tasks for a planned time. But you cannot defer repair.

Plan for success

It’s all about planning

Learning from 25 years of data-based safety training, imagine how positively we can change the record of general aviation accidents.

Flight planning is one of the special topics on our Pilot safety hub.

hello CASA,

Just a short note of appreciation for the safety article reminding myself and other aviators of personal minimums.

l thought it was a well written text.

really excellent article with commonsense overlap that applies to numerous industries. very well done

Excellent article agree one hundred percent.

Great safety advice.