Graham Murphy’s sixty-year career began in a wood and canvas biplane and took him high into the flight levels, behind the glass displays of intercontinental business jets. Many things changed, but the fundamentals stayed the same.

When I left school, much to my father’s disgust I got a job at the local aerodrome straight away. I was what they called a tarmac terrier, washing and refuelling aeroplanes, and asking questions about everything I saw.

I soloed in January 1963 in a DH-82 Tiger Moth. My instructor Beth Garrett (who was the first female RFDS pilot and the first woman to hold an ATPL in Australia) sent me solo at 7 hours 20 minutes. I was 18 years old. She warned me about the rate of climb I would get with only one person on board. I didn’t really notice, but the main thing was I came back with the aeroplane undamaged.

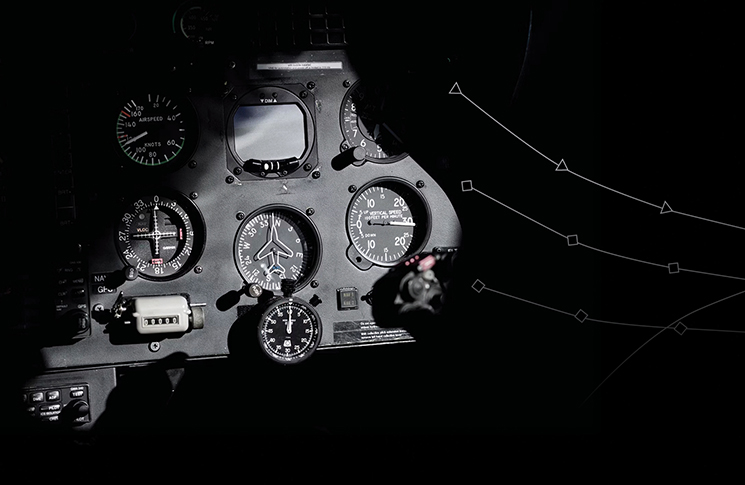

It was sink or swim in those days and while the aircraft were harder to fly, they were also simpler. No radio, no flaps, no nav aids on the Tiger Moth and no gyro instruments apart from a vacuum-operated turn indicator. Even so, the Tiger Moth was a great training aeroplane; it taught airmanship even before you started it (by swinging the propeller). Taxiing was a skill in itself and you had to consciously keep a lookout.

I did my commercial and instructor ratings in a Beech 23 Musketeer with Civil Flying Services in Moorabbin. I went to Perth for a promised job that didn’t eventuate. My would-be employer put me onto a photographer who needed a pilot for a Cessna 206, which in those days was a Star Wars level of machine. I remember the first trip was to North West Cape. The operator gave me a bundle of charts to get there, whereas in Victoria, one WAC chart just about covers the entire state.

Later I became a Junior C grade instructor at the Royal Aero Club of Western Australia. You weren’t taught how to teach – as long as you could fly OK and put the odd briefing up, that was all that was required. It was a baptism of fire. You’d fly all day then they’d want you to fly at night. I was doing 100 hours a month.

I taught Qantas cadet pilots including David Massy-Greene who flew the Qantas Longreach Boeing 747-400 inaugural trip from London to Sydney. But the dumbest thing I did was to turn down an airline job and miss out on that career.

MacRobertson Miller Airlines asked if there was anyone with a commercial licence and morse code endorsement interested in becoming a first officer on a DC-3, but I thought, ‘Who would want to fly that old thing?’ and ignored the offer. A few years later they became part of Ansett.

I returned to Melbourne and did my instrument rating in a Baron. Within a month I got a job with the Victorian Air Ambulance flying a Beech 50 Twin Bonanza. Then I got a job flying a King Air 200 out and back to Lord Howe Island, 4 days week. That was very interesting.

Lord Howe was a one-way strip but the King Air was capable so I enjoyed that. And it was good experience to develop judgement in flight planning and landing performance.

Then I was offered a job in Melbourne on Mitsubishi MU-2s. I ferried new ones from the factory at San Angelo, Texas to Australia. After a series of crashes and mining unions refusing to have their members fly in the MU-2, the operator repurposed them as freight aircraft.

What did I learn from that? Night flying is fatiguing. For example, single-pilot operations, Melbourne to Canberra, a dark night, back of the clock, low freezing level, in a challenging high-performance aircraft – by the end of the week, you needed the weekend to recover.

In addition, there was the time an MU-2 tried to kill me. Just as I got airborne, the autopilot engaged itself and wouldn’t disconnect. It went through its modes – heading, altitude, nav capture. I hit the disconnect buttons and the disconnect chimes went off, but the autopilot stayed on. I found myself at 100 feet with the autopilot commanding a steep turn.

They say you find calm under extreme pressure – I didn’t. I thought I was going to die. What saved me was having been an instructor and the habit of constantly analysing what the aeroplane was doing and why. I reduced power on one engine to stop the roll, managed a left-hand turn and landed unannounced on runway 26 at Essendon. Water had penetrated the avionics bay and short circuited the autopilot.

In the late ’80s I gained an endorsement on the Hawker 800 and flew for various corporate and government operators. One aircraft was based in Singapore and flew to West Africa on business trips. The owner travelled with a suitcase full of cash, which solved many problems. That’s all I’d like to say. Later I worked for a wealthy individual and the highlight of that was having 6 weeks’ paid vacation, in effect, while the aircraft was on standby and the owner was on holiday in Europe.

But many things were changing, including myself. I did the type rating on the Bombardier Challenger 604. It was a six-week ground school, with the sim running between 1 am and 5:30 am. That may be all right if you’re 30 but it pushed the limit for me. I asked the instructor, ‘Am I in the engineer’s course with all this detail?’ He said, ‘It’s complicated but the FAA insist on it.’

My last international flight was in 2021. I didn’t know it was going to be the last but as the flight went on the realisation dawned on me. The 2 other flight crew had type ratings but didn’t speak English and it became effectively single-pilot and the hardest job I’ve ever done. We were collecting a medevac-converted Hawker 800 from Textron at Wichita and returning via Anchorage, Adak (in the Aleutian Islands chain), Sapporo and Seoul.

I found myself at 100 feet with the autopilot commanding a steep turn.

Every day was like a Biggles book. We had a fuel leak at Anchorage, then there was weather and volcanoes erupting at Adak. I’ve seen quite a bit of the world and the Aleutians are among the most spectacular landscapes. But on that trip, I could have done with less scenery and a more straightforward journey.

After we were airborne from Adak, Centre called us with an amended flight plan because of North Korean missile tests. The clearance was given in raw latitude and longitude that I had to put into the FMS. Just what you need – a finger error mightn’t seem much but if you get it wrong there, you’re in real trouble.

At Seoul the inverter failed. The minimum equipment list said the aircraft couldn’t fly with that failure, so I did the last sector as a passenger on an airline flight.

It’s fair to say the trip was more stressful than I would have liked. When I got back to Melbourne, I told my wife, ‘That’s it. I don’t need this type of thing any more’.

But it’s hard to let go completely. After 21,600 hours, I’ve retired into training and checking and the occasional instructor rating – I might make 22,000 eventually. I’m still involved with the Hawker 800 – I do some work for a company in Singapore and a contractor for the WA state government. I quite enjoy it, the Perth organisation in particular is very impressive.

I’ve done nothing extraordinary, I’m just a general aviation pilot. I’ve been well trained, by a lot of ex-military pilots in the early days and had very thorough type training.

If I was asked for my opinion, which is just one pilot’s opinion, I’d say there’s less emphasis on old school airmanship among younger pilots today. And even though you could argue there’s less need for that level of skill – circling approaches are fast becoming a thing of the past, thankfully – it’s still a worry. I see lapses in lookout, checklists and handling skills among some quite experienced pilots.

I think the instructor rating was the best move I ever made and I’d recommend it to any pilot who really wants to improve their own flying. You learn a lot by teaching – about people, about yourself and how to diagnose and recognise issues in flight. Personalities, nerves and what the aircraft is up to. An instructor rating also opens the door to training and checking and, when you apply for a job, it looks good on your resume. It saved my life on the MU-2.

More options for instructors

We’ve streamlined the application and assessment process for individuals who don’t employ other staff, to obtain a Part 141 flight training certificate.