Understand the threat, and don’t wing it through icy conditions this winter.

Flying in winter has many perks, such as smooth crisp air and a reprieve from the Aussie heat. However, the cooler weather is also a time for increased icing encounters, particularly carburettor and airframe icing.

While not every pilot has experienced icing firsthand, it’s a serious issue that can affect the performance of an aircraft. Understanding the common conditions that can lead to icing and the appropriate safety precautions available, could save your life.

Carburettor icing

This type of icing typically occurs when the temperature of the fuel-air mixture drops below freezing, which can happen in conditions with high humidity and low air temperature. As the mixture cools, the moisture in the air condenses and may freeze, forming ice inside the carburettor.

The ice can clog the carburettor, disrupting the fuel flow and resulting in power loss or, at worst, complete engine failure, followed potentially by loss of control inflight. There are methods to avoid carburettor icing.

1. Monitor air temperature and humidity

One way to manage carby icing occurring is to monitor air temperature and humidity. This can be done during flight planning – forecasts and weather reports provide a valuable insight into what conditions you can expect en route.

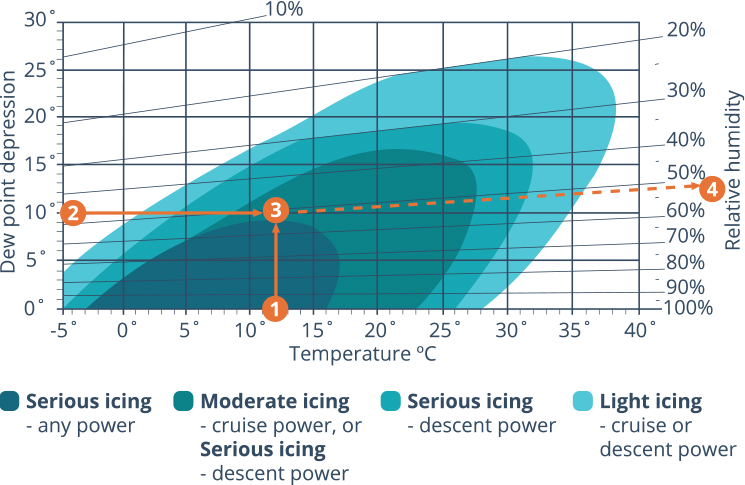

CASA’s Carburettor icing probability chart is a helpful aid to evaluate the potential icing risks on any given day. It is available online or in your VFRG.

Michael White, CASA Aviation Safety Advisor team leader, says the chart is a quick reference guide for predicting the development of carburettor icing.

It doesn’t have to be freezing cold for carby icing conditions to exist

‘The chart provides the extent of icing, ranging from light and moderate to serious, using cruise and descent power and critically, if serious, at any power setting,’ he says. ‘It’s also easy to use by following the step-by-step instructions on the card and helpful in pre-flight preparation and in-flight reference.’

2. Carburettor heat system

The carburettor heat system is a pilot’s best friend – the key method to beat icing. The system blows hot air from the engine into the carburettor to prevent the mixture from cooling and condensing.

Checking the carby heat system during run-ups is a crucial step as pilot in command, so make sure to complete this on your take-off checklist.

During run-ups, activate the carburettor heat control to see if hot air is flowing into the carburettor. To check if it is functioning correctly, pay attention to the RPM. Applying the carby heat on a fixed-pitch propellor aircraft should reduce engine RPM slightly, as the hot air is less dense. On aircraft with a CSU, the manifold pressure will decrease. If icing is present, the engine will run roughly until the RPM stabilises and increases again.

‘Remember, it doesn’t have to be freezing cold for carby icing conditions to exist, so always use carby heat when practising forced landings,’ chief aerobatic instructor at the Aerobatic School Sydney, Joel Haski, says.

‘If carby heat is part of your procedures, always follow the procedure and avoid second guessing whether it may be needed or not.’

Should carburettor icing be suspected in-flight, immediately turn on the carby heat and increase the engine RPM to clear the ice. When applying the carby heat, rough running and a slightly lower RPM can be expected at first; a return to the original power setting should occur once the ice has cleared.

3. Maintaining the carby heat system

Regular inspection and maintenance of the carburettor heat system isn’t something to take lightly. As a pilot, you should check the system before take-off, as mentioned above. However, it’s also important to have a LAME check the system regularly.

Eric Cieslar, chief engineer at Airag Aviation Services, says, ‘The importance of carburettor heat systems often gets overlooked. While carb ice doesn’t only occur in colder months, now’s a good time to ensure your maintenance provider checks everything is in order – especially if you’re flying IFR.

‘Another thing to remember is that some aircraft are more susceptible to icing than others. Know your aeroplane and how your carb heat system works.

‘For example, some aircraft have a carb heat temperature gauge inside the cockpit, which informs rather than warns of what the carburettor air temperature is. Others use the RPM gauge to determine if it is functioning properly. Whatever system you have, perform your ground carby heat checks properly.

‘Ultimately, if you’re a licensed pilot flying anywhere near icing conditions, you should have sufficient training to know what you’re doing. If you’re jumping into a new or less familiar aeroplane, get your instructor to provide you with a systems overview.’

Wing icing

While there are many forms of icing, the icing on aeroplane wings is one of the most dangerous weather hazards affecting aircraft performance – especially in cold and humid conditions. When moisture in the atmosphere freezes on the wing surface, it forms a layer of ice and will affect the performance and safety of an aircraft – and the safety of its passengers.

Essentially, as the ice accumulates, the shape of the airfoil changes, reducing its lift and increasing its drag. The weight of the aircraft also increases. In severe cases, icing can result in a stall at a higher airspeed and lower angle of attack. Loss of altitude, reduced airspeed and increased fuel consumption can also become problematic factors when dealing with icy wings. Yet again, solutions are available to help you enjoy winter flying and keep you safe.

Combating ice on wings

Some aircraft have anti-icing systems, such as de-icing boots or heated wing surfaces. Both systems are activated inflight by the pilot when icing conditions are experienced.

How do they work? The boots are inflatable rubber bladders that break up the ice on the leading edges of the wings. Like an aircraft wing, a propeller is also an aerofoil. However, when de-icing elements are installed on propellers, they are electrically operated – heating the root of each blade to melt the ice.

And, of course, heated wing surfaces also use electrical elements to prevent icing occurring in the first place.

So, what if you don’t have these features in your aeroplane? Well, it comes down to efficient and effective flight planning – and using common sense.

It doesn’t have to be freezing cold for carby icing conditions to exist.

60-second icing recap

Avoid low air temperatures and high humidity: Monitor weather conditions and avoid areas with low air temperatures and high humidity – conducive to carburettor icing.

Use carby heat: The system blows hot air from the engine into the carburettor to prevent the fuel-air mixture from cooling and condensing to form ice. It’s your secret weapon against icing.

Make use of CASA’s carburettor icing probability chart – available at our online store or in the VFRG.

Comments are closed.