Up there, wishing you were down here – an often-told story but chilling every time.

During the hour-building phase of my commercial pilot licence training, I was planning my longest ever VFR cross-country trip, a journey of about 750 nm each way with some overnight stops on the way, with 2 passengers. I’d never undertaken anything this ambitious before, so I was determined to get it right.

I tried to check all the boxes: plotted performance charts for the shortest runway I planned to go to (assuming the most pessimistic temperatures). did careful weight and balance checks. called everywhere I planned to go to get a local briefing and carried emergency supplies since the flight would be through a designated remote area for much of the trip.

What concerned me the most was the weather so I also called the BOM and got my first weather briefing from a real person. They were very helpful and friendly and I suggest more pilots try calling the number at the bottom of every GAF more often. The weather briefing confirmed my assessment of the situation – my biggest issue was going to be getting out of Melbourne where the cloud base was low but, once out of the city, the skies were clearing up at my planned destination and alternate.

On the morning of the flight, I watched the weather anxiously and delayed my departure for 3 hours while waiting for the cloud to disperse enough to allow a take-off. With accommodation already booked and paid for, I knew get-there-itis could be a factor but tried to base my decision solely on the conditions. I decided that, based on the current forecast available, I should be able to get out of Melbourne and into clearer skies, so we took off.

Flying along a VFR lane at 1,500 feet, I had to make a big decision just minutes into my flight. Ahead of me loomed a large wall of scattered to broken cloud, with bases of around 700 feet and tops of perhaps 3,000. I couldn’t keep going straight. My choice was to go underneath it – scud running quite low to the ground – or climb over it. If I went under it, I knew I would have high terrain coming up, which would require a massive detour to get around at such a low altitude, plus my passengers would be in turbulence for a long time. Going over it meant getting cleared into controlled airspace, which I did have the endorsement to do, but had not utilised much, so I lacked confidence.

In hindsight, I didn’t spend enough time considering my third option: turn around and land. I decided to go over it and asked for clearance to 4,500 feet to get above the cloud. This was granted and up we went. For a while this seemed like a great decision – we enjoyed beautiful views and smooth air and cruised without a care. I was aware of my position fixing requirements – every 30 minutes for a VFR aircraft – and identified landmarks through gaps in the clouds as we went.

After a while, the gaps in the clouds started to become less frequent. I thought about descending through one, but remembered my weather briefing and decided to press on to the promised clearer skies ahead. I checked the METAR for my destination and my heart sank, as I read ‘OVC043’. Overcast. No holes back down.

I checked every nearby airport. Overcast. I looked around me. Overcast. I checked my watch, realised it had been more than 30 minutes since my last position fix and the gravity of my situation began to sink in.

After some time of desperately searching for a hole to descend through, I decided to ask for help. I radioed ATC, explained my predicament and asked if they had any reports of gaps in my vicinity. They asked a few airliners, all of whom reported overcast skies with even higher tops from their vantage points high above me.

I checked the METAR for my destination and my heart sank, as I read ‘OVC043’.

After a pause, a new controller arrived on frequency and asked, ‘Are you instrument rated? Do you have a GPS or autopilot on board?’.

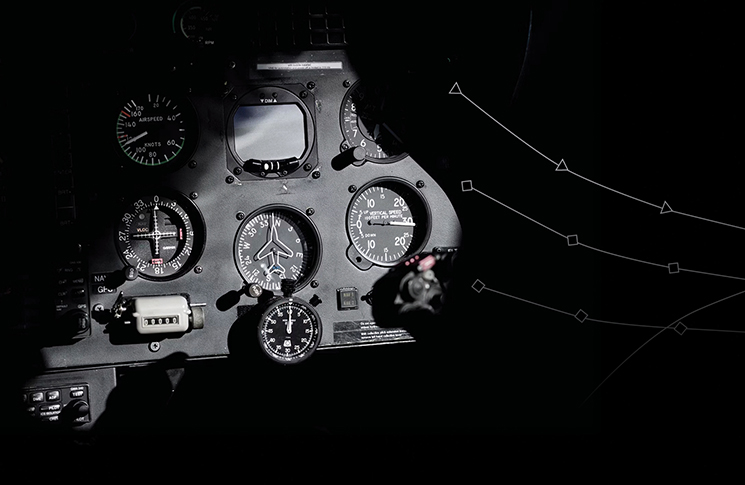

My aircraft was basic, with only analogue gauges, and I was navigating via an EFB (and backup) and paper maps, so I sheepishly responded, ‘Negative to all’. After another long pause, ATC issued the most nerve-racking instruction I have ever received: ‘Squawk 7700’.

At this point, I had my work cut out for me. ATC were of course trying their best to be helpful, but in this situation they also posed a potential hazard. For example, at one point I spotted a very tempting gap whiz by below me. I turned 180 degrees trying to find it again, spotted it and began to descend, just as ATC called to ask me to report my fuel endurance in minutes and provide a latitude and longitude position.

Distracted, I glanced at my iPad to find the latitude and longitude, then looked back outside to realise I am about to fly into a cloud. Aviate, navigate, communicate. I focused on flying the plane, climbed back above the clouds and said ‘standby’ and got myself back into a controlled cruise configuration. The elusive gap melted back into clouds and was gone.

I did a quick fuel calculation (I still had two and a half hours remaining, thankfully) and find the latitude and longitude and report it, so at least they have my position. I’ve wandered outside this frequency’s range by now, but ATC manage to relay a message to me via a passing airliner and we got back on a suitable frequency.

I’m provided with possible options for alternates, but all have reported conditions worse than my destination. I’ve already decided that turning back is a poor choice, because I know the conditions are worse in that direction and it’s much further to return than it is to press on.

My plan B is to set up a wings-level 500-feet per minute descent and penetrate the clouds while staring at the instruments, but I don’t want to resort to this unless endurance becomes an issue.

My plan B is to set up a wings-level 500-feet per minute descent and penetrate the clouds while staring at the instruments.

Finally, I see a gap that looks just barely big enough to get through. I don’t have much time to react, so I make a split-second decision to go for it. I flick on the carb heat, pull the power to idle, put out a stage of flaps and slip the hell out of it. Descending at a rapid rate, we punch through the hole, just 20 miles or so from our destination. It’s a huge relief. I report our safety to ATC and thank them profusely for their help and land. They called to check up on me and were nothing but caring and supportive.

Lessons learnt

My takeaways from this experience (besides the obvious of wanting to get my instrument rating) are that you should respect the weather and be prepared for the real conditions to be worse than forecast. As a VFR pilot, never commit to flying above cloud unless you are 100% certain you can get back down. After a long lunch break to calm my nerves, I did end up flying the next leg of my journey that day. But this time, when I saw clouds ahead, I went under them.

Have you had a close call?

8 in 10 pilots say they learn best from other pilots and your narrow escape can be a valuable lesson.

We invite you to share your experience to help us improve aviation safety, whatever your role. You may be eligible for a free gift just for submitting your story.

Find out more and share your close call here.

Thanks for sharing. I can imagine that feeling in your guts when you realised there was a problem.

Life would be easier if you could always guarantee you’d get accommodation after you’d finished flying for the day. It would certainly remove any “get-there-itis”.

I hope the rest of your trip was great.

Similar thing happened to me. Ended up with Plan B (500fpm descent through clouds on Auto Pilot), with a local base operator making IFR calls to ensure the area was clear of other traffic. Popped out over the sea under a OVC008 layer. Never again. It was the flight that made be determined to get my Instrument Rating.