If you plan shrewdly, a general aviation tour of Tasmania can be a scenic, safe and enjoyable experience

So you’ve decided this is the year for the Big Safari. Borders are open; you’ve saved up some travel pennies and you even have some friends who are still willing to fly with you.

You won’t be surprised to hear that the success of a long range, multi‑leg trip lies in the planning. And I’m not talking about who gets the master suite with the spa bath. There are so many elements to factor in. Here are a few to think about.

There’s a million-dollar view out the window that makes this crossing so worth the effort.

Pick a latitude

Timing should be a prime consideration. As this is the winter edition of the magazine, let’s talk about the cold stuff. We’re heading into winter. Or maybe where you live, you’ve been flying in wintry conditions for a couple of months already. And OK, hello Top End, we all know it’s paradise up there in winter. Quit your bragging.

I’m going to state the bleeding obvious here and suggest that heading south of the 40th parallel in mid-winter might not be a first-choice plan. But let’s talk about it, for that moment when your first-born rings up and tells you their baby is due in July and they’ve found a great B&B for you, just around the corner … from the Hobart hospital. Expectations are high.

Forget all the potential goo-gars coming out of the maternity ward – all you’re seeing in front of your face is Bass Strait. Let’s get you down there.

Bass Strait

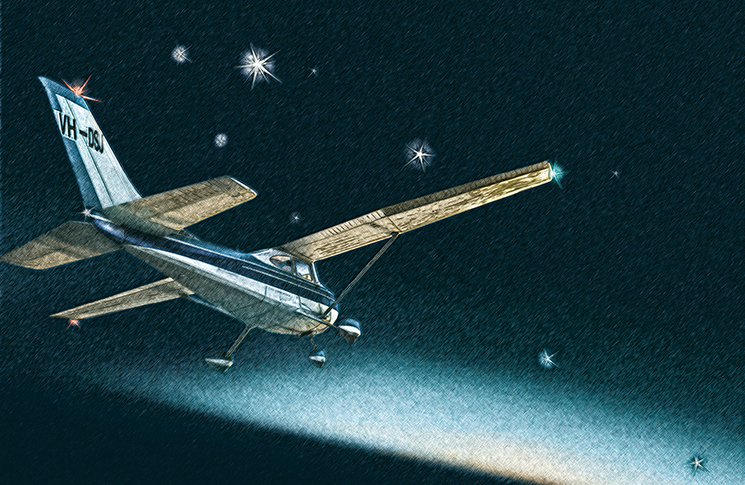

Think of it like this – flying across the strait is way more comfortable than slogging southwards on a Sydney-Hobart yacht. You’ll still need a lifejacket, but there’s a really high chance you won’t be getting it wet. And there’s a million-dollar view out the window that makes this crossing so worth the effort.

The rules for flying IFR and VFR across Bass Strait have some similarities. The regs are in place for good reason, so have a read of the over-water rules on carrying and wearing lifejackets. (CASR Part 91 Plain English guide). Your lifejacket needs to be a CASA-approved one, rather than a marine lifejacket. I find that rule totally fascinating, but this is perhaps not the forum for that particular discussion. You’ll also see that life rafts are required (one seat per pax) when over water and more than 100 nm from a suitable landing area.

That brings us to an interesting point – suitable landing areas. Despite the chances of engine trouble over water being no more likely than when we’re flying over land, our internal watchhouse kicks in and says, ‘How about planning over blobs of land when we’re crossing large stretches of water?’

But what’s the real point if those blobs of land are big enough for 2 seagulls to land and that’s about it? Yes, they are specified waypoints which define our track for Melbourne Centre and others in our fleet. But, if we’ve taken the eastern route across the strait via Flinders Island, for example, it’s not until we’re cruising over Deal Island that we see a useable welcome mat. In any case, we’ve now had that decision made for us.

Let’s check out the rules in the ERSA. The often-neglected section towards the back, Special Procedures (GEN‑SP-1), is a must-read when planning a trip to Tassie. Unlike in days gone by, Airservices has now mandated the routes across Bass Strait for non-scheduled air transport operations, specifically for ‘single-engine aircraft and multi-engine aircraft which are unable to maintain height after an engine failure’.

The procedures direct you onto routes via King Island or Flinders Island, with nominated smaller islands as mandatory waypoints. That goes for IFR flights as well as VFR. So, although the ERC shows more direct IFR routes, IFR pilots in the above category must now comply with SP‑1. (That is, unless they’re flying something capable of maintaining height after an engine failure!)

Keep reading down that ERSA page and you’ll get to the bit about over‑water skeds – recommended VFR reporting procedures as you cross Bass Strait. These simple calls to Melbourne Centre advising your operations normal status are a logical inclusion in the procedures, and why not take advantage of an added safety watch if it’s being offered?

Just check the ERC before you fly and take note of the changing frequencies for Melbourne Centre at various points across the Strait. IFR pilots are in touch with Centre as normal and so do not have to request these specific over-water skeds.

From coast to coast, you’re only over water for about an hour, depending on your aircraft, but that’s time enough to climb up to a nice high altitude. The view’s way better up there and we know that height means distance when it comes to gliding, so it’s a no-brainer really. If you’ve got a forecast ceiling of 4,000 feet, maybe tomorrow would be a better idea. Tell that baby to wait.

Tassie weather

So, back to the maternity ward. Seriously, what happened to Spring babies? You know, the traditional New Year conception? OK, I’m getting distracted. It’s just that September/October would be a lot warmer than July in Tassie. Now we have to contend with checking those pesky freezing levels.

Icing concerns on your flying days should be front and centre. It’s no use hoping it doesn’t happen; just don’t put yourself in that situation. For a little island like this, Tassie has some serious mountains, particularly in the ranges between Strahan and Launceston where the lowest safe altitude can be above 6,000 feet. So, if the sun disappears and the forecast is for low cloud, you’ll need to forget the trophy pic over Cradle Mountain and seek out some clear air over lower terrain.

Cloud tends to build up along the north coast with any sort of onshore air flow, from the north-west around to the north-east. Often Bass Strait can be clear, but the cloud may be sitting against the hills at the very north of Tassie. A quick check of the cloud base at Wynyard or Devonport may be useful.

The thing about Tassie is that there are options. We did 3 trips down to Tassie earlier this year and the weather was different each time. On one circumnavigation – St Helens to Strahan clockwise – we did not see a single cloud around the entire coastline.

Sometimes, if the high country is socked in, the coastline can be clear. If the east coast is sparkling like a diamond, the west coast might be getting pounded by a westerly front. You’re fair in the path of those unforgiving roaring 40s, the prevailing westerly winds off the Southern Ocean, and they can get cranky. Low cloud, poor visibility and dangerous mountain waves on the lee of high terrain can make VFR flying a no-go zone.

On one of our flying days in January, half of us flew IFR Wynyard to Hobart in solid IMC the whole way. The other half few VFR in clear skies down the west coast past Strahan and along that spectacular south coast getting a suntan. They didn’t see any cloud until just south of Hobart. Glue yourself to the BOM resources and make plans that are flexible.

IFR pilots note: just like at many airstrips in regional and outback Australia, approach procedures are not in place at every destination in Tassie. Keep in mind that the weather can change very quickly down here, and plenty of thought needs to be given in the planning stage to workable alternatives.

Spoilt for choice

I have to agree with a lot of touring pilots who admit a PIFR or a CIR is a handy rating to have under your belt down here. Of course it all depends on your luck, but Tassie is one destination where you may find yourself flying just as many IMC days as VMC, regardless of the season. But as long as your itinerary is flexible, VFR pilots can wait out bad weather in any one of a dozen magnificent locations on this beautiful island. And the good part is, it takes no time to catch up on your itinerary – Tassie is tiny.

Keep in mind that the weather can change very quickly down here.

Our favourites keep growing, but we love Wynyard so much we now try and stay 2 nights. The hospitality of the Wynyard Aero Club members is legendary. They offer their clubroom, courtesy car and a super friendly welcome to all itinerant pilots, so make sure you call in and say g’day if you’re scooting along that north coast. Devonport has fuel and friendly locals too.

Once you get down to the big smoke, ATC in Hobart Tower are incredibly helpful, but give them a break and get yourself fully up to speed with the Hobart VTC and ERSA entries for Hobart and Cambridge before you get there. And while you’re at it, if you haven’t flown in controlled airspace for a while, dive into the AIP for a refresher on those ATC readbacks (AIP Gen 3.4 Para 5.4).

The prize at the end of all this safety related stuff is that you now get to hug that new baby. And when you’ve had enough of that, give the child back and turn your thoughts to heading home. Even if you flew the east coast southbound, do it again heading north. It’s that good.

Tasmania’s east coast offers us the ultimate bucket list flight. I’m not usually lost for words but the coastline between the Tasman Peninsula and St Helens in the north is breathtaking. As long as you observe the Fly Neighbourly Procedures in ERSA (FN 18 & 23; the FN pages follow the SP pages), you can choose whatever altitude you like for the best views. A best photo competition when you get to Wineglass Bay is mandatory.

Plan ahead so you are well prepared for all contingencies and Tassie will deliver some of the most scenic flying on offer in Australia.

|

Editor’s note: After joining an IFR ‘air safari’ to Tasmania in late March, I can endorse the recommendations by Shelley Ross in this story for a safe and enjoyable flight. For this low-hours hobby pilot, it was an experience of a lifetime – the bucket list item you hadn’t realised was even available. Or achievable. On a previous group flight to Moorabbin, I was terrified to find myself over water – solo – with crowded St Kilda beach offering no welcome if the engine failed. This time, I admit to being quite nervous again – even with an instructor onboard – as I headed out from East Sale military airspace to Cliffy Island to join the prescribed route across Bass Strait. However, the safari was a delightful blend of IFR and VFR and I became (reasonably) comfortable over water, even at 2,000 feet around more remote areas such as the south-west capes. I learnt so much as I put more than 20 hours in my logbook, refreshing radio calls and CTA procedures and doing every RNAV possible – while missing out on the ILS at Launy due to RPT traffic. The ever-changeable weather meant Frenchmans Cap was majestic in brilliant sunshine but Wineglass Bay appeared dim though misty rain. But overall, a great experience, one that has left me determined to retain the refreshed PIFR proficiency. *Ross Peake travelled in his own time, at his own expense. |