A New Zealand accident involving two professional instructors and a modern well equipped aircraft is a story of how a combination of individual lapses and organisational weaknesses can create a tragedy

It was perhaps an unusual activity for a Saturday night but otherwise was a routine training flight. Its purpose was to build the command IFR hours of a young, obviously keen, and moderately experienced pilot.

Another similarly clean-cut young man with about the same number of total hours (about 820) was in the right‑hand seat of the Diamond DA42 diesel twin to act as safety pilot. Both were Category B instructors but had relatively low instrument flight hours.

The pilot’s 141 IFR hours consisted of 82 hours in a ground simulator, 44 hours of in-flight hood simulation and just under 14 hours of actual IFR flight. Tonight’s flight would add to that.

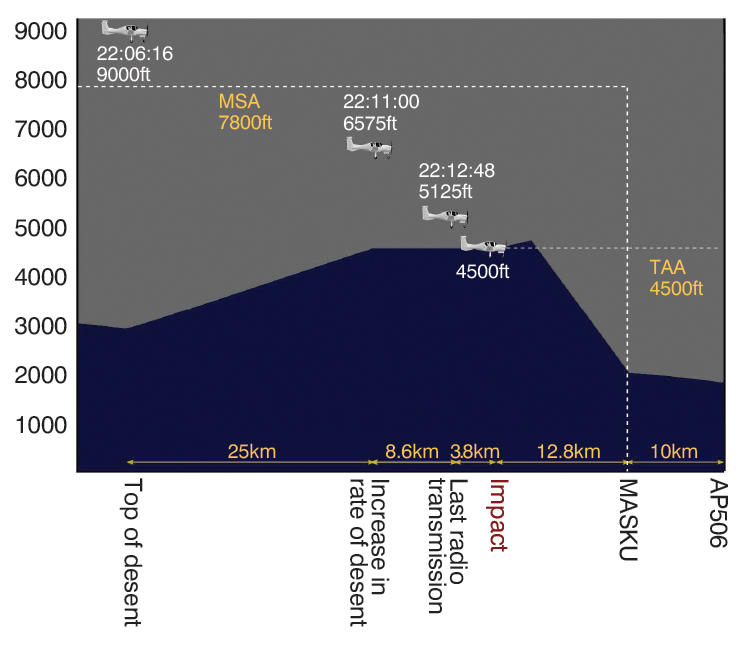

The second leg of their journey over New Zealand’s North Island was from Palmerston North to Taupõ, where the plan was to fly a missed approach and continue to Ardmore, near Auckland. Thirty minutes into the flight, while at 9,000 feet, the DA42 was turned away from the planned track and the pilot made a ‘top of descent’ radio call to the flight information service. The aeroplane began a descent. About 8 minutes later, at about 10.13 pm, the aircraft struck the Kaimanawa Range about 38 km south of Taupõ at about 4,500 feet, destroying itself and ending two lives.

The pilot had planned an approach to Taupõ that involved flying north to the reporting point known as TAIKI, then turning to approach the aerodrome from the east. Instead, at the reporting point TARUA, south of TAIKI, the pilot made a 35-degree left turn to approach Taupõ from the south‑east.

The report by the New Zealand Transport Accident Investigation Commission found the reason for the change in flightpath could not be fully established. ‘However, it was very likely influenced by the weather, both current and forecast,’ it said.

The impromptu, autopilot-directed turn at TARUA was probably a route to the reporting point at MASKU, an initial approach fix for Taupõ’s runway 35. In view of the deteriorating weather over the central North Island (which included isolated towering cumulonimbus), the pilot may have thought saving some time by literally cutting a corner on the planned route was a prudent move. But this move brought several problems.

He was now flying an unevaluated route – in broad terms he was ‘going off-road’ in the sky. New Zealand’s Civil Aviation Rules only allow this ‘random routing’ above flight level 150 in uncontrolled airspace, such as that of the central North Island. Random routing below FL150 is only permitted in controlled airspace and requires clearance from air traffic control.

The minimum safe altitude (MSA) at MASKU is 4,500 feet, but en route to that point, it is 7,800 feet. Surveillance data showed the aircraft making an apparent controlled descent to 4,500 feet, but doing so well before MASKU, instead striking a high ridge in rugged terrain.

He was now flying an unevaluated route – in broad terms he was ‘going off-road’ in the sky.

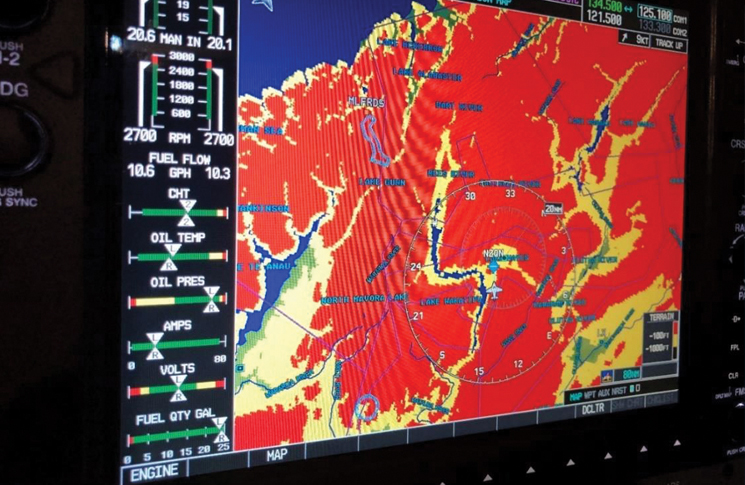

The DA42 is a modern aircraft equipped as standard with a terrain proximity awareness system on its Garmin G1000 display. This shows terrain within 1,000 feet in yellow and turns red for terrain within 100 feet of the aircraft’s GPS computed altitude. The commission found it was very likely this system was either ‘excessively dimmed or not selected, so the terrain ahead was not displayed during the descent’.

The G1000 offered a Class-B terrain avoidance and warning system at extra cost, but the aircraft was not equipped with this option. Whether its urgent synthetic voices would have saved the aircraft will never be known.

Planning and permission

The flying school that employed the two pilots had a scheme allowing staff to use school aircraft to build their experience. These flights normally had to be authorised by a training management instructor but on that Saturday evening, none were at the premises. The pilot could have phoned a training management instructor to get authorisation but did not do so. Instead, he self-authorised the flight despite having followed correct procedure for all his previous flights under the scheme.

A review of the school’s records found this self-authorisation had never been done before by anyone. The problem had not been organisational ‘drift’ but a latent weakness in procedure. This was exploited, for unknown reasons, by a pilot described as ‘knowledgeable and conscientious’. The duty instructor at the school that day, also a Category B, did not feel able to override the pilot’s decision.

The school said if a senior instructor had examined the proposed flight plan and weather information, the flight would most likely not have been authorised. This was because of the high MSA for the planned route, which a light twin-engine aeroplane such as the DA42 would struggle to maintain should an engine malfunction occur. After the crash, the school amended its standard operating procedures so the chief flying instructor’s approval was required for any single-pilot IFR navigation flights, other than those routes specifically listed.

The commission found the operator’s flight-authorisation procedures were not sufficiently robust to prevent students and qualified pilots conducting flights without the requisite authorisation from supervising instructors.

The commission listed 3 lessons identified from the inquiry:

- pilots, especially instructor pilots, should be fully aware of the parameters prescribed by the Civil Aviation Rules, including for navigating away from pre‑planned and instrument flight rules-approved

flight routes - where possible, pilots should use and be proficient in the full capabilities of the flight instrumentation systems available to them

- flight training schools should ensure their procedures for flight authorisation and supervision are sufficiently robust to ensure that pilots can only conduct training flights after obtaining appropriate authorisation and supervision.