Icing is a year-round hazard, as a recent Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) report makes unsettlingly clear.

On 19 December 2019, a turbine powered Cessna P210N departed Bankstown Airport, in Sydney, for a private flight under instrument flight rules to Cambridge Airport, near Hobart. It carried a pilot and one passenger.

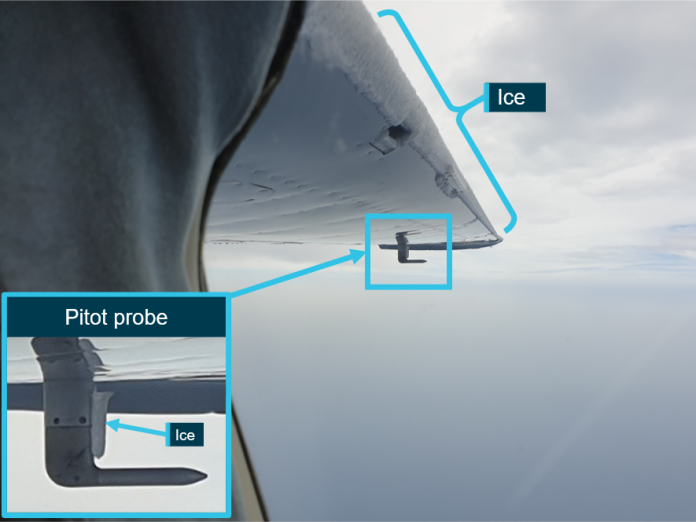

Shortly after reaching cruise altitude of about 18,000 feet, the Cessna encountered icing conditions. The pilot requested and was granted ATC clearance to descend to 16,000 feet. During the descent, the pilot deactivated the propeller de-ice and engine ice-protection systems. Another engine ice-protection system, which functioned automatically when the aircraft was pressurised, continued to operate. At 16,000 feet, the pilot made several track deviations to avoid entering cloud. The pilot also took several photographs, including one which showed ice on the leading edge of the left wing and pitot probe

Then the engine stopped, and could not be restarted. The ATSB concluded the Rolls-Royce 250 turbine had ingested ice after one of the engine protection systems was turned off. As the engine suddenly cooled, it underwent rotor lock caused by differential cooling that temporarily locked the turbine. Knowing the risk of rotor lock, the pilot had attempted a restart within about five seconds of shutdown, before cooling could begin. This was unsuccessful and the pilot declared mayday and was directed to Moruya airport.

The pilot found the aircraft behaved differently in a real glide to the way it had handled during simulated glide training. In the real event the aircraft glided better, losing less altitude. The pilot put down the landing gear and at least 10 degree of flap, at about 6000 feet, to lose altitude. The aircraft arrived at Moruya from the south at 8000 feet, circled to approach runway 18 but was too high. The pilot continued the orbit but after encountering turbulence and windshear was now too low for another attempt at runway 18.

A shark patrol Robinson R44 was in the vicinity and the pilot remembered the increased workload of looking for it despite the fact that the helicopter pilot, not wanting to become part of the Cessna’s problem, was hovering offshore at 200 feet. Uncertain about the position of the helicopter, the Cessna pilot rejected landing on runway 36 or runway 22. Abeam the threshold of runway 18, at 300 feet, the pilot realised a landing was unlikely and continued northward, slowing and instructing the passenger to tighten their seat belt. The aircraft struck trees and crashed 560 metres north of the airport just under an hour after taking off. It was destroyed, with the pilot seriously injured and the passenger receiving minor injuries.

ATSB Director Transport Safety Stuart Macleod stressed that pilots should carefully evaluate all available relevant meteorological information when determining whether icing conditions are likely along the planned flight path.

‘Where the aircraft is not certified or equipped to operate in icing conditions, any ice-protection systems on the airframe, propeller or engine should be regarded as a means to provide time to exit unexpected icing conditions, not to continue to operate in those conditions,’ Macleod said.

He also emphasised the importance of forced landing practice.

“Although forced landings can occur in a variety of circumstances, in general, pilots should focus on remaining visual with the intended landing area in order to accurately assess the aircraft’s performance in glide, and reach key decision points to refine the course of action,” Macleod said.

The investigation also identified a number of other factors associated with pre flight preparation and the operation of the aircraft and its systems.

I won’t comment about this forced landing – I wasn’t there.

I learned to use S-turns and side slips to adjust my aiming point for forced landing. Keeping the nose well down and the wings unloaded when manoeuvring.

What are Students taught about controlling their aiming point these days?