The pilot was overloaded and inexperienced – but this tragedy was also an organisational failure by the operator

By Nick Stobie

It’s a shocking sight – an aircraft emerges from the clouds, spiralling and pointed almost vertically down, before disappearing into the forest below.

This footage was how we learnt that an aircraft had crashed in Umeå, Sweden, on 14 July 2019. Any aircraft accident is heartbreaking, but it wasn’t until it emerged the aircraft was a GippsAero GA8 Airvan, that Australia really sat up and took notice.

At the time, the Airvan was one of the most successful Australian-made aircraft in production, with more than 240 delivered throughout the world. With the wreckage of one of those aircraft, a turbocharged model registered SE-MES, now scattered across several hundred metres of Swedish forest, it quickly became clear an in-flight breakup had occurred. Tragically, within the wreckage was a pilot and eight skydivers, all killed by the impact.

Five days later and with the cause of the breakup unknown, CASA grounded Airvans within Australia. The European Union Aviation Safety Agency followed with an Emergency Airworthiness Directive only hours later. And CASA’s Principal Airworthiness Engineer, David Punshon, boarded a plane and headed to Sweden.

Sifting through the wreckage

He met representatives from the Swedish Accident Investigation Authority (SHK) and was briefed on the events and what they’d uncovered. The wreckage had been taken to a storage facility just outside of Stockholm. From the footage, investigators knew the aircraft’s right wing and tail empennage had detached but they didn’t know why.

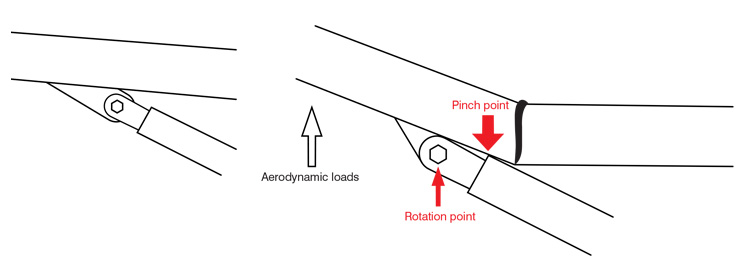

However, the wreckage displayed clues about the breakup. The lower skins of the right wing had creases, with the direction of the ripples showing how the wing had twisted. The top skin had been crushed above the strut attachment, indicating the right wing had folded up and detached. This was consistent with an overstress, likely in a ‘rolling G’ manoeuvre, where the aircraft pulls a high load factor while simultaneously rolling.

The horizontal stabiliser, detached from the aircraft but largely intact, showed signs of breaking in overload rather than in flutter. It was increasingly looking like the aircraft had been subjected to conditions well beyond what it was designed for.

‘It was apparent that this plane didn’t just break up because of bad maintenance or corrosion,’ Punshon says. ‘The aircraft had just had an annual review. Everything pointed to the aircraft being airworthy. To get it to fail the way it did, it had to have had exceeded the limits it was approved for.’

Following this realisation, he informed CASA of his observations that indicated the grounding should be lifted at once. The GA8 Airvan itself wasn’t the likely cause of this accident and the fleet returned to the sky after five days.

Putting the puzzle together

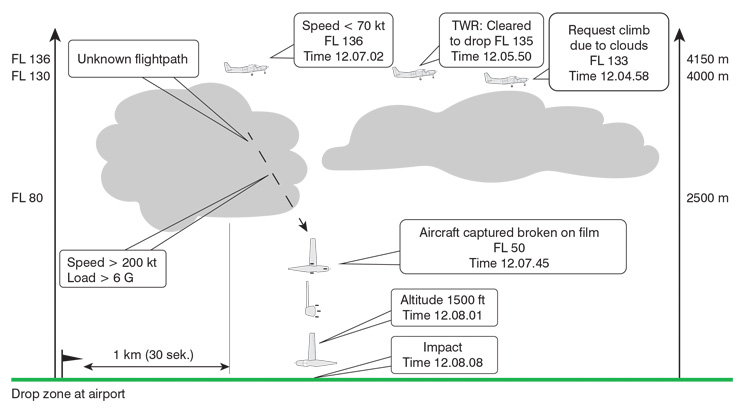

The investigators knew this much about the last flight of SE-MES – it was a skydiving sortie, planned to FL130 (13,000 feet) and with 8 skydivers on board. The aircraft was only 7 years old and had just more than 1200 hours in service. It was the third flight of that day. In contrast to the previous 2 flights which were able to proceed normally, cloud at the intended drop height had prompted the pilot to request to drop from a higher altitude. Radar data showed how the flight progressed from there.

After manoeuvring to hold while awaiting clearance, the aircraft was established on the ‘jump run’ or final approach to the drop. SE-MES’s airspeed was decreasing as it reached a peak altitude of FL136. One kilometre short of arriving overhead the airport (and drop zone), SE-MES suddenly changed direction to the left and began descending rapidly, at a nose-down angle of more than 60 degrees. The aircraft was last observed by radar 60 seconds later, at an altitude of 1475 feet. Calculations estimated a true airspeed above 200 knots (exceeding VNE) and forces exceeding 6G, possibly higher.

Given the decreasing airspeed immediately beforehand, then the sudden change of direction and descent, a stall and subsequent departure from controlled flight was suspected. In a spiral descent, the aircraft likely entered the cloud below. The unsecured skydivers might have been thrown around the cabin, possibly exacerbating control issues or even impacting the pilot.

The investigators hypothesised that the aircraft, out of control and spiralling, picked up speed and subsequently overloaded the right wing, which detached. With the right wing missing, the aircraft rapidly rolled to the right, causing the horizontal and vertical stabilisers to separate as well.

The question was – how did SE-MES get into this state?

A complex operation

Parachute operations, despite being considered private operations in both Sweden and Australia, are complex with challenges beyond typical private flying.

Throughout these flights, the workload on the pilot is high. Drop altitudes are often contained within controlled airspace, requiring the pilot to negotiate clearances and adapt to ATC instructions. The aircraft must be navigated to a precise drop location, while reducing power and airspeed in preparation for the skydivers to exit the aircraft. The skydivers must also be kept in the loop, giving them ample notice to prepare for the jump.

Pilots sometimes contend with weather, as was the case with this accident. Local weather reports and footage documented broken cloud with a base of approximately 8000 feet, with cloud tops extending between FL110 and FL140 – around the height of the drop. Swedish regulations did not permit the intentional dropping of skydivers in or into cloud, adding to the task for the pilot who was not instrument rated.

Hypoxia is a real threat at these altitudes and the aircraft was not carrying supplemental oxygen. The subtle impact of mild hypoxia on decision-making and task performance would have added further strain.

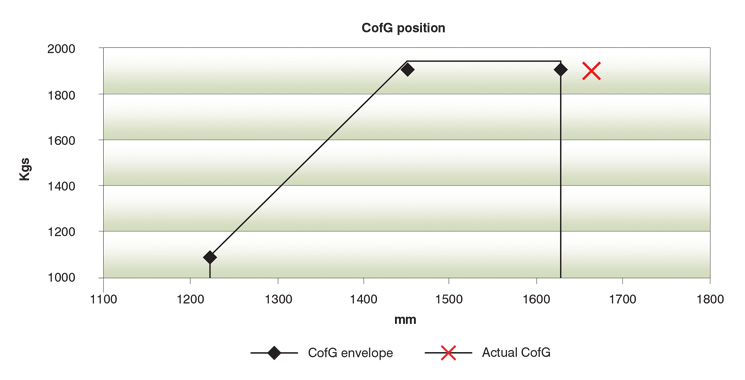

Jump aircraft are often operated close to maximum take-off weight and often towards the aft centre of gravity limit. In the case of SE-MES, the aircraft departed 40 kg above MTOW with its centre of gravity located behind the aft limit. During the jump run, the parachutists in an Airvan move towards the rear door, shifting the centre of gravity further aft, reducing stability, and requiring the pilot to make constant adjustments to maintain level flight.

Considering what the pilot was facing, it is easy to understand how the accident happened. The task-saturated pilot, in an overloaded aircraft, avoiding cloud, slightly hypoxic, fails to correct as the load shifts aft. Unstable, the aircraft pitches up, slows, stalls, the left wing drops and the aircraft spirals into the cloud below, never to emerge intact again.

But understanding how it happened doesn’t tell us why.

Pilot in command

Skydiving is a well-trodden route into aviation for new pilots. The pilot of SE-MES was likely walking this path as well. He started flying in 2009 and, by the end of 2011, had completed the CPL with a night rating, in 165 hours total time.

In the 8 years between completing his training and beginning to drop skydivers in April 2019, he accrued only 40 more hours, partly due to sinus problems. His licence was valid and current, having completed a proficiency check (akin to Australian biennial flight reviews), 6 months prior.

By the day of the accident, the pilot had 215 hours total experience, including 12 hours on the GA8 Airvan. As he had previous experience (albeit limited) on an aircraft with a constant speed propeller and an electronic flight instrument system, Swedish regulations required only that he familiarise himself with the aircraft type – there was no formal training required or documented on the GA8 Airvan.

Swedish regulations also did not require any specific training for dropping skydivers, other than the pilot have at least 200 hours total time. The skydive club for which he was flying provided him with informal training; however, again this wasn’t documented. The accident flight was his 25th skydive sortie and only his 8th without a supervising pilot.

Organisational deficiencies

Umeå Parachute Club is a non-profit sports skydiving club founded in 1967.

The SHK’s report detailed that in many areas, the club had good procedures established. There were well documented procedures for flying the GA8 Airvan, specific to parachute operations. But the report also detailed deficiencies, 2 of which contributed to the accident.

The club had no procedure for calculating weight and balance on each flight. Each flight manifest listed the names of each skydiver, but not their weight. Anecdotal evidence highlighted in the report suggested that weight and balance was ‘done based on experience, and you feel on the ground if the aircraft is too tail heavy and the parachutists can then be asked to move forward’.

The pilot had been trained by the parachute club. The SHK report said, ‘The circumstance that the person responsible for flight operations at Umeå Parachute Club went along as a parachutists [sic] on the second flight of the day suggests that there were no question marks regarding the pilot’s perceived ability to perform the flight under the conditions that were present at that time’.

And that’s the key to why this accident happened – the conditions that were present. The pilot was clearly capable of operating the aircraft under the previously benign weather conditions. But, given the conditions that were present, the report noted the pilot’s ‘ability was not on parity with the complexity of the flight under the conditions in question’.

The pilot was in too deep, the organisation’s defences didn’t catch this and the outcome was tragedy.

Organisations that fail to take positive safety steps and manage risk will invariably

have uncomfortable questions to answer.

Responsibility for risk management

In most private flying, the pilot in command bears responsibility for identifying risk and acting to mitigate that risk. It is incumbent on all pilots to know their limitations and, as this accident clearly demonstrates, being licensed to fly an aircraft, and even trained for a specific task, does not necessarily equip you to fly in all conditions and circumstances.

But where private operations are under the remit of an organisation or club, there is a compelling argument that the responsibility for risk management is with that organisation, even outside the environment of an Air Operator’s Certificate. Without extinguishing the responsibility of the pilot, these organisations have a duty to ensure their pilots and aircraft operate safely and put systems in place to do so.

In the case of Umeå Parachute Club, this might have meant systems to ensure aircraft weren’t manifested above maximum take-off weight.

It might have meant formal training, similar to the jump pilot authorisation (JPA) the Australian Parachute Federation issues. It is a short course delivered by an experienced skydive pilot, covering both theoretical and practical aspects of dropping skydivers. To be issued with a JPA, a pilot must have a CPL or 200 hours total time, among other requirements. In Australia, this qualification is mandatory for any pilot dropping tandem or student skydivers.

It might have been a period of indirect supervision to provide guidance in making operational decisions, such as how to handle cloud impeding the drop run.

It might have been a safety management system to identify these type of issues.

I was given the advice that if you’re ever unsure about a decision in aviation, think about how you would explain it to the coroner if things went wrong. Organisations that fail to take positive safety steps and manage risk will invariably have uncomfortable questions to answer, even if technically complying with regulations as a private operation.

By the letter of the law, in private operations the buck stops with the pilot. But in private operations that are genuinely complex and challenging, it’s the organisation that must bear at least some of the burden. It was once acceptable for organisations to simply defer to pilots’ judgement, training and skill on the grounds that it was private operations – this accident is yet another example of why that paradigm can no longer remain.

Mandatory reading.

A truly tragic accident, which no doubt could have been avoided, if more adequate training had been given by the operator with no fault being attributed to the low time pilot! 😲😨

I believe there also needs to be some soul searching by regulators.

There are many, essentially commercial, operations which advertise their product at a price which exceeds the actual operating cost. Thereby adding a commercial margin within the price to allow the operation to pay for advertising, administration, ground support staff , pilots and at the end of the day a small profit. The accident report highlights the well known fact that this particular type of operation employs young and relatively inexperienced pilots. No doubt some if not all are paid a remuneration for their efforts.

The question for regulators is why do some commercial operations require an AOC and all the protections that go with it and others are allowed to escape the basic public protections embodied in the certificate process.

A casual conversation with people who have paid for and undertaken these and similar flights reveals that many do not really understand the standards accepted by CASA for licensing and the medical requirements let alone, in some cases , relaxed airworthiness requirements.

As to this particular accident I would disagree with John Brett. It is indeed an easy way out to blame the pilot however all licensed pilots are responsible for basics such as weight and balance. The more difficult aspect is the maturity to exercise the essential authority of pilot in command.

This accident also probably exposes the very poor understanding many graduate pilots have of the importance of the position of the centre of gravity to stability and speed control particularly at high weights and angle of attack.