By Thomas P. Turner

We’re taught we should use checklists, but do we know why and how to use them?

Air crash investigations frequently cite this as a contributing factor: the pilot failed to accomplish checklist actions. Fuel starvation, electrical failure, departure stall, gear up landing—most could be avoided if the pilot had simply used a checklist. More correctly, the mishap would not have occurred if the pilot had accomplished the actions contained on a written checklist.

Many years ago I flew a Beech Bonanza on a one-hour flight. I dropped off a passenger and took off again for home. My workload was high as I leveled at 8000 feet, deviating around an emerging line of storms.

I was level for about 20 minutes when I noticed I’d forgotten something—the mixture control was still in the full rich position. This was correct for climb in the turbocharged aircraft, but in cruise it meant I was burning about 90 litres per hour—50 per cent more than specified in the pilot’s operating handbook.

It was not critical on this particular flight as I had 280 litres of usable fuel when I started and still had 180 litres on board for the second take-off. Even at full rich that gave me about two hours’ fuel for the one-hour trip home. However, if I was flying further, my mistake could have caused me to run out of fuel en route even though the POH said I had plenty to make it with a reserve. How could I have caught my error sooner? That formative flight caused me to become a big proponent of checklists and flows.

Checklists

Think back to your first flying lesson. You walked through a preflight inspection with your instructor, then settled into the left seat for the first time. Though it seems so simple now, you were amazed at the complexity of the controls and instruments and radios in that little trainer.

You were probably relieved when the instructor handed you a small book or laminated card that contained everything you needed to do, in sequential order, to make sense of this chaos and bring a seemingly complex machine to life and fly at your command. Read a step, do a step—that’s probably how you learnt to use this checklist. That is an effective way to learn the proper order of actions, but there are two very common errors associated with this type of checklist use:

- using the checklist as the instigator of your actions is cumbersome, especially in the air

- the checklist is seen as a temporary crutch to be overcome, then discarded once you ‘learn to fly’.

Most instructors teach checklists as a ‘do list’—do this, so that happens—instead of what it really is designed for: to check you haven’t forgotten something as a result of workload.

Why checklists are important

The Boeing B-17 was one of the most successful warplanes in history. Thousands upon thousands left massive defence factories for combat. The Flying Fortress developed a deserved reputation for saving its crewmembers by absorbing the worst that could be thrown against it and, more often than not, making it home. But the entire Boeing B-17 project was nearly halted before the war ever began. And it was because of a checklist.

In the 1930s aircraft were becoming very complex and it was difficult for pilots to train quickly enough to keep pace with progress. With war looming, Boeing responded to a

US Army proposal for a bomber with the Model 299, a four-engine behemoth the Air Corps designated the YB-17 (‘Y’ for prototype). In isolationist prewar America, the big Boeing was under intense public scrutiny when one of the YBs crashed on take-off from Wright Field near Dayton, Ohio, the Army’s primary engineering test base.

The professional test crew had forgotten to disconnect the tail’s gust lock before take-off. The big silver ship crashed into a hill off the end of the runway and was completely consumed by fire. The crew was lost but the B-17 program survived. The Army immediately began requiring the use of checklists for all pilots in all phases of flight—a policy now prevalent in aviation around the world.

Why checklists are important to you

If a professional flight test crew can die for forgetting something as simple as a mechanical gust lock, then workload and pressure to ‘go’ can cause everyday pilots like us to sometimes forget critical items.

Some of the most common accidents result when something simple is forgotten. Pilots run out of fuel because they forget to lean the mixture or switch fuel tanks when needed. They crash on take-off because the trim is set incorrectly or flaps are used (or not used) as needed, or they forget to latch a door, window or canopy. Altitudes are ‘busted’ and clearances are violated because a pilot does not follow procedure for a departure, level off or approach. The ultimate ‘Oops, I forgot’—forgetting to extend landing gear—is absolutely preventable with proper checklist use.

The most common checklist deviations happen when an outside distraction—weather, sick passenger, radio call, another aircraft in the pattern—interrupts a pilot’s normal routine.

If you get distracted while running a checklist, the safest thing is to go back to the beginning and verify you haven’t forgotten anything.

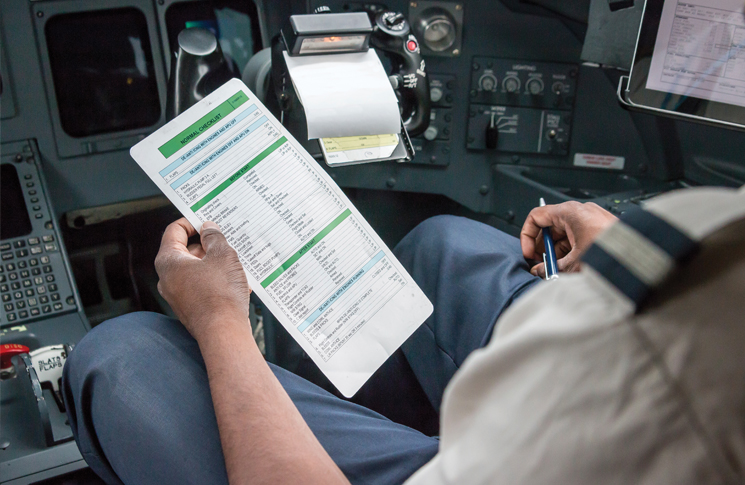

Printed checklists

Printed checklists can be cumbersome to use in flight. That’s one reason many instructors demonstrate, intentionally or not, the use of checklists for start-up and before take-off checks, then throw the book in the back of the aircraft or shove the laminated card in a sidewall pocket.

However, checklists have great value in all phases of flight. How do you use them correctly? Establish a flight condition or attitude (climb, cruise or descent) from memory. Then, as time permits, pull out the printed checklist and ‘check’ that you didn’t forget something. If I had been in this habit when I flew that Bonanza trip, I would have leveled off, completed all actions to the best of my memory and then immediately found my leaning omission when I verified my actions using the level-off checklist.

Mnemonics

Some instructors teach diligent use of mnemonics or memorised checklists. Used consistently, these are excellent checklists in their own right. One of the most famous is CIGARTIP as a before take-off check:

- controls free and correct

- instruments set

- gas/fuel sufficient for flight and proper tank selected for take-off

- angle of flaps

- run-up magneto, carb heat and propeller checks as appropriate

- trim set

- interior set—seatbelts, doors and windows latched

- pattern checked for other aircraft.

If you’re an instrument pilot, you probably remember the four, five or six ‘T’s (depending on your aircraft) for crossing a fix:

- turn

- time

- tune (radios)

- tyres (gear down as appropriate)

- throttle

- talk (report to ATC).

Another frequently used for landing is GUMPS:

- gas/fuel set to proper tank

- undercarriage down and locked

- mixture set

- propeller set

- switches (fuel pumps, etc.) set.

A disciplined pilot uses a combination of printed and mnemonic checklists to fly safely. Commercial operators and especially the airlines have taken this a step further, creating a concept that is also extremely useful in a high-workload, single-pilot aircraft. It’s called the cockpit flow.

Flows

Airlines developed the cockpit flow as a means of quickly accomplishing actions in a complex aircraft at times when there might not be time to run through a printed checklist. Flows are a memory aid, which of course is the goal of all checklists. Cockpit flows also work well to verify what you did from memory is what you think you did, and that the aircraft is properly configured for whatever comes next—a ’check’ list.

A cockpit flow is a structured pattern that mirrors a printed checklist. It’s a memory aid and can be used for normal, abnormal and emergency procedures. Since those flying in single-pilot operations have to do all the work themselves, the idea of a cockpit flow has great promise. Just ‘look around the cockpit’ and make sure you’ve not missed anything.

Of course, without some structure, ‘looking around’ has limited value. You need to make certain you look at everything that’s necessary. Professional training organisations develop pictorial flow references for most foreseeable manoeuvres and tasks. The flow for a normal procedure task, like configuring for an instrument approach, might look something

like this:

- power: SET

- flaps: SET FOR APPROACH within flap operating speed

- attitude: ESTABLISH as appropriate for speed and altitude requirements

- airspeed: ESTABLISH

- trim: SET

- avionics: CONFIRM SET FOR APPROACH.

A simpler way is to set things the way you think you should and then, starting at the point of your choice (for instance the attitude indicator or the upper left corner of the instrument panel), look across the panel from left to right, then across the circuit breakers and lower subpanels from right to left and then finally along the seats and floorboards from left to right, for things like fuel selectors, etc.

A quick but methodical visual sweep of the cockpit should help catch anything that was forgotten or misconfigured. It takes only a few seconds but if you’re disciplined to do it every time you change configuration, altitude or attitude, the cockpit flow is a tremendous boost to the safety of a single-pilot aircraft.

Checklists and flows

Have you ever forgotten where you put your car keys or to pick up some milk on the way home from work? Did you ever start your engine with chocks still under the nosewheel or, like me in the Bonanza, discover you’d missed a seemingly obvious action like leaning the mixture? Then you need to use a checklist.

If you do things right, a cockpit flow will become as natural to you as rolling into a bank to turn. And you will wear out your printed checklists from use confirming your memory actions. That’s okay, because as you learn and experience more, and as equipment is added or removed from the aircraft, you’ll want to revise and personalise your checklists for the most efficient ways to fly.

The best use of a checklist comes in concert with flows and mnemonics. Here’s how to use in-flight checklists:

- configure the cockpit for the desired flight activity from experience and memory, including use of mnemonics

- crosscheck with a practiced flow pattern to confirm everything is where you think it should be

- as time permits, reference a printed checklist to make certain you didn’t overlook or forget something.

And here’s why—use flows and confirm with printed checklists and it’s much less likely ATSB will be reporting about you.

Comments are closed.