Audio adds a new dimension to Flight Safety Australia reader Nic Barnes’ story about how things are different up north

As a VFR private pilot from Adelaide, I have enjoyed many years of flying clear skies, relatively safe and largely flat terrain, and the easy airspaces of Parafield and Murray Bridge.

I had logged the bulk of my flying time around South Australia, apart from the odd flight to Bankstown, Archerfield, and Essendon.

Upon moving to Darwin to start a new life three months ago I realised I had been flying all those years in a comfort zone. Over the years I have been extremely careful not to get myself caught out in bad weather, cancelling flights when the aviation weather forecast looked doubtful and diverting when unexpected weather built up over the Blue Mountains on those interstate trips.

Flying the Top End is a whole new world. I arrived towards the end of the wet season with its unpredictable weather and cloud, then the start of the dry season, when at times you can have smoke haze to contend with. I am only just getting comfortable with Darwin Airport’s runways, taxiways, restricted airspaces and procedures.

On this particular morning I was looking forward to my flight to Hodgson Downs. After studying notams and weather, reading cavok for Darwin to Hodgson Downs, lodging my flight plan, and doing a thorough pre-flight. I fired up the trusty Piper Lance and listened to the ATIS, which included a report of 6 km visibility through smoke haze and said to expect visual approach. I briefly looked south towards my direction of travel and could see the haze, which didn’t look all that bad from where I was. I also noticed a temperature inversion, which seemed not very high.

I had never experienced smoke haze from the air before, so I hardly even gave it a second thought. I thought, ‘it’s just haze, like the name says, right?’ I was thinking it was going to be a great day flying.

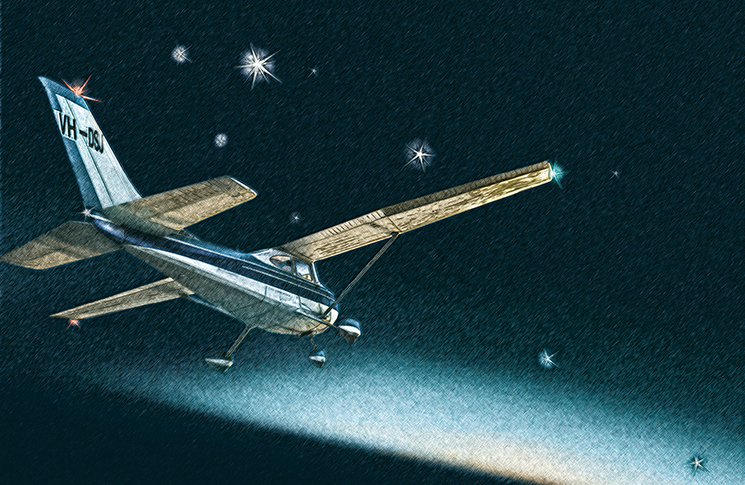

After being cleared for take-off from runway 18, I started the climb-out to my assigned altitude and as expected was told to track for Channel Island. This is not usually a problem but this time I quickly lost sight of the earth below and found I had no natural horizon. I had inadvertently taken off into a very thick area of smoke haze.

The Lance has a single-axis autopilot and I had already set the heading bug to my assigned heading on the ground. I turned it on so I wouldn’t have to worry about keeping wings level. Of all times for the autopilot to fail! Instead of locking onto the heading bug and maintaining my track the aircraft turned sharply, obviously to some other heading that was set before the failure.

The old saying ‘always trust your instruments,’ went through my head. (In hindsight this means trust only the primary instruments). When I looked at the artificial horizon it was showing I was sideways. My sensory perceptions were telling me I was straight. After correcting the bank, I stayed focused on the artificial horizon with glances to the ASI and VSI to maintain the rate of climb. Confusion set in as I thought I must have set the bug incorrectly and found myself fighting the autopilot for a few seconds to reduce angle of bank. (I trusted that autopilot for five seconds too long.) After double checking my settings were correct and the autopilot had indeed failed at the worst possible time I turned it off and focused on keeping wings level, airspeed and a gentle rate of climb. I also started a careful gentle turn to regain track before anyone noticed. Too late – I heard the approach controller telling me I was off track. I did think about descending to get below the so-called haze but the complete whiteout started about 200 to 300 feet and I knew the terrain rose to about 300 to 400 feet along my track within 30 DME – so this wasn’t an option.

I felt the best action was to keep climbing for the inversion which shouldn’t be much higher. I found that the concentration of flying on instruments was so intense I had difficulty responding to the controller (It’s ten times harder doing it for real than in practice). Eventually about 3500 feet I broke out into clear air. What a relief.

The rest of the flight was uneventful. It was easy to see the course of the smoke haze, It seemed like half the Northern Territory was ablaze with large areas of remote bushland alight all the way well south of Katherine.

A few days later when returning to Darwin there was still smoke haze below an inversion that started at Jabiru. It didn’t seem as bad as it was a few days earlier. After I obtained Darwin clearance I was asked to descend. I was not comfortable with that after the event a few days earlier and requested to maintain altitude. Thankfully, the controller obliged and within 15 nm of Darwin there was a nice clean parcel of air.

What I learned

- Don’t shrug off smoke haze as just being haze. It can be thicker in some parts than others and just as bad as flying into cloud.

- VFR pilots in the Top End should get some basic instrument training regularly, whether under the hood or in the simulator.

- Always trust only your primary instruments

- Make use of the autopilot

- Speak up if you can. The controllers are a very helpful bunch

Have you had a close call? 8 in 10 pilots say they learn best from other pilots and your narrow escape can be a valuable lesson. We invite you to share your experience to help us improve aviation safety, whatever your role. You may be eligible for a free gift just for submitting your story.

Find out more and share your close call.

Thanks Nic, a good lesson there for all of us – don’t ignore the need to practice flying by instruments. Perhaps those of us who normally fly VFR should seriously think about doing some time “under the hood” or in the simulator as part of our biennial flight reviews.

It seems this accentuates the importance of a totally independent backup ADHRS instrument if you can? The new mini Garmins and others can be had for a reasonable price. Some aircraft have a glass Dynon Skyview in addition to a Garmin 795/6

Whoever this pilot is, he deserves a raise or, at least a bonus. He used a lot of caution but kept his head to protect himself and the aircraft.

What a hero!

Kim Tolson.

Very informative article Nic. Just shows how quickly our wits need to be turned on to full attention.

I disagree with Phoenix. A little knowledge can be dangerous. Having a little bit of practice in something not fully understood or trained for completely can lead to having a confidence greater than our actual ability and that can lead us all into situations that require a lot of luck to get out of. If you want to fly on days when low visibility is forecast or present, even above VFR standards, then get an instrument rating and fly an instrument rated aircraft. The training alone will improve your flying skills and although challenging, very rewarding and fun too.

Don’t forget: Superior pilots uses their superior knowledge to avoid situations that require the use of their superior skill.

Ditto, a little bit of knowledge can be dangerous! You are either fully VFR or you are not, half and half doesn’t cut it! With so much glass available today it’s making the VFR driver think he is invincible! Few understand the ramifications of an instrument rating, there’s a LOT more to it than being able to keep the wings level on cloud!

5000m viz is a bloody challenge in a high perf plane VFR!