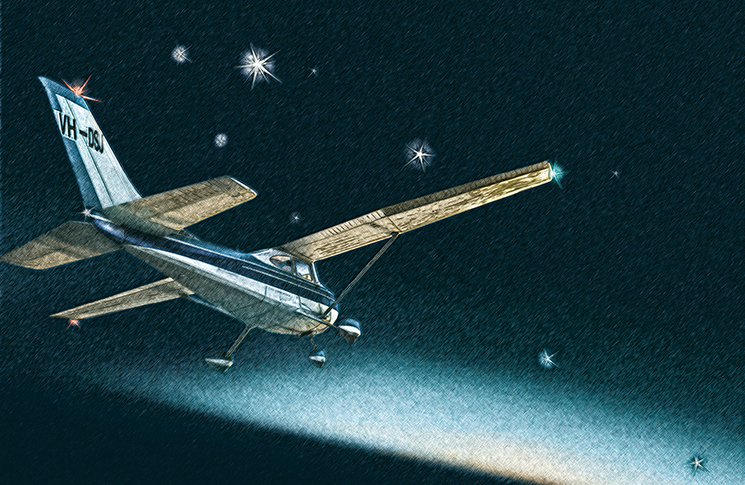

The young pilot’s last words were spoken in the studied unconcerned register of a seasoned aviator. ‘Is there any known traffic below five thousand [feet]?’ Fred Valentich asked Melbourne Flight Service at 19:06 on a calm clear October evening.

Flight service officer Steve Robey answered, ‘No known traffic.’

Valentich replied, ‘I am – seems [to] be a large aircraft below five thousand.’

Robey said, ‘What type of aircraft is it?’ to which Valentich replied, ‘I cannot affirm. It is [sic] four bright, it seems to me like landing lights … the aircraft has just passed over me at least a thousand feet above.’

Valentich’s next utterance was dramatic. ‘It’s approaching right now from due east towards me … It seems to me that he’s playing some sort of game. He’s flying over me two, three times, at speeds I could not identify.’

After affirming his altitude of 4,500 feet, Valentich said, ‘It’s not an aircraft. It is … as it’s flying past, it’s a long shape … [Cannot] identify more than [that it has such speed] … [It is] before me right now, Melbourne.’

Robey asked how large the object was.

Valentich replied, ‘It seems like it’s stationary. What I’m doing right now is orbiting, and the thing is just orbiting on top of me also. It’s got a green light and sort of metallic. [Like] it’s all shiny [on] the outside. It’s just vanished … Would you know what kind of aircraft I’ve got? Is it military aircraft?’

Robey: Confirm the, er, aircraft just vanished.

Valentich: [Now] approaching from the southwest … the engine is, is rough idling. I’ve got it set at twenty three, twenty four, and the thing is, coughing … that strange aircraft is hovering on top of me again … it is hovering and it’s not an aircraft.

There was silence for 17 seconds followed by an unidentified staccato noise, probably transmitted from an open microphone, that ended abruptly.

Valentich and his aircraft were never seen again, despite a four-day search that began at once. But by Monday morning, radio, TV and newspapers were reporting his final conversation and disappearance. ‘UFO MYSTERY’, proclaimed The Australian’s front page.

Many versions of the story say no wreckage was found. This is now known to be not quite true. A cowl panel from a Cessna 182 was found on King Island in 1983. And a 1978 Federal Department of Transport report, uncovered in 2012, said search aircraft had spotted but lost sight of a debris field.

The usual suspects

The mystery is that there is no mystery.

– Cormac McCarthy

Before going further, it is important to consider the usual suspects, the mundane factors that killed pilots in 1978 and still do so in 2024.

Aircraft

The Cessna 182 was fresh from a 100-hourly inspection and Valentich was confirmed to have loaded sufficient fuel for the flight.

Weather

A letter from the Bureau of Meteorology to the Department of Transport describes the evening. ‘Conditions were perfect for night flying … no cloud was detectable between the Victorian Ranges and the northern Tasmania coast … There was no turbulence and visibility was excellent. An airborne aircraft over King Island at 1000 GMT (7 pm local time) could clearly see the light from Cape Otway Lighthouse.’

Pilot

Reports about Valentich, who had 150 hours, were mixed. Although anecdotes from those who knew and flew with him described him as meticulous and careful, he had failed all 5 commercial pilot licence (CPL) theory subjects twice and in July 1978, had failed 3 of those subjects a third time. He had told his family and friends he was one subject away from

obtaining his CPL.

‘Fredrick Valentich was rapidly running out of time,’ the department’s summary accident report of 1981 says about his flight training. The report quotes Valentich’s girlfriend Rhonda Rushton as saying he ‘wasn’t himself Friday night’. But family and other friends quoted in departmental files are adamant he would not have planned to take his own life or disappear.

Flight planning

Valentich held a class 4 instrument rating, enabling night VFR flight. He had given various reasons for his flight from Moorabbin to King Island. Depending on who he told, it was to pick up friends or crayfish.

Cinema verité

The Indianapolis Centre scene from Steven Spielberg’s film Close encounters of the third kind (1977) is a masterpiece of suspenseful filmmaking that well stands the tests of time and changing tastes. It describes an encounter with an unknown flying object (UFO) in a terse and technically accurate tone that comes in part from Spielberg’s casting of air traffic controllers rather than actors. This startling realism adds to its emotional persuasion. A remarkable aspect of the dialogue is how similar it is to the real conversation between Valentich and Robey, from the first insouciant inquiry about traffic in the vicinity, to a rapid encounter with an unknown object at close quarters.

Only the endings are different.

It is highly likely that Valentich saw Close Encounters which premiered in Australian cinemas in March 1978. The files on the disappearance include an interview with his father,

who said:

Fredrick was a firm believer in UFOs. He had saved articles and information on UFOs, read Chariots of the Gods and other books, and went to see movies on the subject … His belief had strengthened recently when he was allowed to see the RAAF’s confidential files on UFOs at East Sale and Laverton.

Rushton told departmental investigators Valentich had said to her a few days before the flight, ‘If a UFO landed in front of us now, I would go in it, but never without you.’

‘UFO MYSTERY’, proclaimed The Australian’s front page.

Expectation: the power of hope

Since 1978, the term cognitive bias has entered the aviation lexicon. Cognitive biases are shortcuts in our thinking that normally relieve mental load but can obscure reality and hazards. Expectation bias is now recognised as a cognitive bias and a killer in aviation. It normally occurs in much more mundane contexts than seeing a UFO – a pilot wrongly ‘sees’ a safe switch position while reciting a thoroughly memorised checklist (Spanair flight 5022, 2008) or lines up to land on a taxiway that looks like a runway, because the parallel runway they are cleared to is closed (Air Canada Flight 759, 2017). Or you see an aerodrome that you gratefully presume to be your destination, but which is in fact somewhere else (Ethiopian Airlines flight ET‑3891, 2021).

Expectation bias also affects observers on the ground. Historian Brett Holman has written on UFO sightings in Australia in 1909 that were often described as airships, although no such aircraft were flying in the southern hemisphere at the time. The explanation matched the current popular interest in aviation, Holman writes.

Astronomer and former US Air Force pilot James McGaha thinks Valentich most likely saw the planet Venus.

Mystery and tragedy

Astronomer and former US Air Force pilot James McGaha thinks Valentich most likely saw the planet Venus, which would have been at a bearing of 255 degrees and 25 degrees above the horizon, according to departmental files.

‘A computer search of the sky for the day, time, and place of Valentich’s flight reveals that the four points of bright light he would almost certainly have seen were the following: Venus (which was at its very brightest), Mars, Mercury, and the bright star Antares,’ McGaha writes in a 2013 Skeptical Inquirer story.

Expectation bias, spatial disorientation and pilot distraction are real, and can kill you regardless of your beliefs.

‘These four lights would have represented a diamond shape, given the well-known tendency of viewers to “connect the dots” and so could well have been perceived as an aircraft or UFO,’ he says. He suspects Valentich’s description of the object orbiting him is a description of the young pilot falling victim to a tilted horizon illusion, which can occur when the sun sets but still brightens part of the horizon. It was Valentich who was orbiting, spatially disorientated after tilting his wings to match the false horizon. This would soon have become a spiral dive.

However, philosopher Patrick Stokes, who investigated the Valentich disappearance for ABC Radio National, says confirmation bias is double-edged.

‘In the department files, they seem to have decided early on that it seems to be a deliberate disappearance, that seems to be the tenor,’ he says. ‘But remember they’re doing this investigation 22 months after the Connellan Airlines disaster in Alice Springs [where a pilot took his own life and killed 3 others]. There’s an element of suggestibility – this looks like the last thing, so that’s what it is.’

Stokes says every subsequent development has allowed the mystery to continue and people to project their own interpretation onto the facts.

‘If you’re a UFO sceptic, it’s easy to see a story of disorientation,’ he says. ‘If you have a human factors background, it’s easy to see Valentich as someone whose career as a pilot was failing and had reasons to disappear or die. Equally some people believe there’s no explanation other than the extra-mundane.

‘Occam’s razor says we go for the simplest explanation and that makes it hard to prefer any kind of extraterrestrial explanation. But it’s also hard to say just what did happen.’

to King Island over Bass Strait | Public domain

Setting sun

Fred Valentich’s disappearance remains a mystery but at the same time, there are lessons to be learnt from it. In a universe of one septillion stars (1023, or 1 followed by 24 zeros), extraterrestrial life is a valid subject of speculation. But expectation bias, spatial disorientation and pilot distraction are real, and can kill you regardless of your beliefs. Their antidotes may seem boring by comparison with interplanetary craft but are all we have: crosschecking and verbalisation, believing your instruments and being practised in using them, aviating before navigating or communicating, and thorough flight planning.

Had Valentich not disappeared, he may have been about now coming to the end of a long aviation career, perhaps in cabin crew, engineering, airport operations or ground handling. Like many of us who fall in love with aviation, he may have, with maturity, come to accept that his role in the system would involve his feet staying firmly on the ground but would be no less vital because of this.