How dumb luck prevented an intergenerational technology disaster.

If you walk around a classic car show, you will inevitably hear someone say, ‘They don’t make ’em like they used to’. This is meant to imply that the quality of older machinery is superior to that of its modern counterparts. However, this seemingly innocuous saying holds a much deeper and more sinister meaning for the aviation community. I was to discover this for myself one misty autumn morning several years ago.

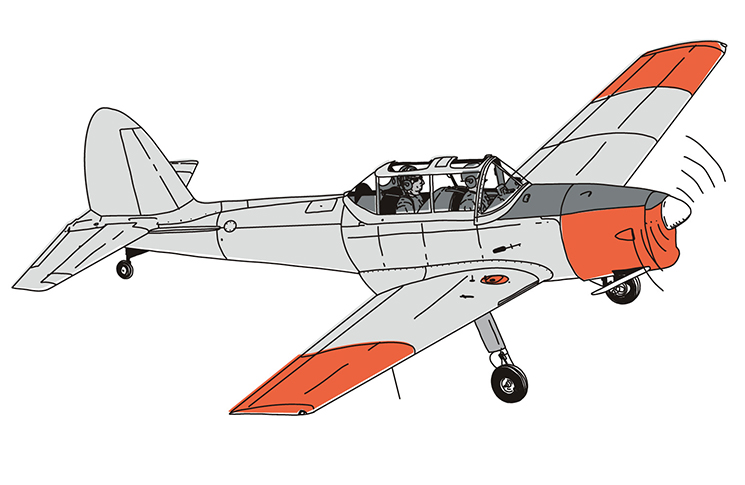

In April 2012 I was the proud co-owner of a 1947 de Havilland Chipmunk. My co-owners and I had recently completed an eight-year restoration of the aircraft and it had been flying for just more than a year. I felt I knew every nut and bolt in that aircraft and was certainly well across the many WWII-era ‘peculiarities’ that had been incorporated into its design.

Having grown up on a diet of 1980s American aircraft, it was fascinating to learn how to operate an aeroplane that had no toe brakes, a mixture lever that worked in reverse, no carby heat control and a starting procedure that was something akin to performing voodoo magic. Even shutting down the engine involved a different procedure to an American aircraft. On this particular day, one of these peculiarities would almost bring me undone.

I have had 3 partial-power failures-after-take-off incidents in my long and undistinguished flying career. The second of these took place at Moorabbin Airport in 1991. It was one of the Royal Victorian Aero Club’s competition days and a youthful version of myself was strapped into a Piper Warrior with one of the club’s instructors alongside to perform judging duties. Having completed the run-up checks, we lined up on runway 35L and began the take-off roll. Not long after getting airborne, the engine began to run like a dog. We were able to maintain height but had no idea how long it would last. We quickly determined that we had enough power to get around the circuit for a return landing if the engine kept running. Once we had a plan, my instructor said very succinctly, ‘You fly the aeroplane, I’ll try to figure out what is going on’. She commenced troubleshooting and discovered that if she reduced the throttle setting, the engine would run normally; at full throttle it would run very roughly. A reduced power circuit was completed, much to our joint relief.

The club mechanic subsequently determined an ignition problem had developed that would only surface once the engine revolutions got higher than 2,400 rpm, much higher than what was used for the pre-take-off checks.

Fast forward 21 years and a much more wrinkly version of myself is strapped into an immaculately maintained de Havilland Chipmunk on the apron of Cootamundra Airport. It was a typical autumn morning, with temperature around 12 degrees, and a touch of moisture in the air. Having waited out a bit of a fog delay, I completed the daily inspection (including testing the fuel for water) and found the right combination of voodoo magic to get the engine primed and started. I completed the pre-take-off checks, including what passes as a magneto check in this aircraft. I say this because the brakes are so ineffective that the run-up can only be done at around 1,400 rpm. With everything seemingly in order, I made the short taxi out to runway 34 with the canopy cracked slightly open and unknowingly lined up for what would become my third partial-power failure-after-take-off incident.

The engine started to run like a dog, with lots of coughs and pops and a bit of shaking going on.

It all started pretty well. I gently fed the power in while peering down the side of the nose to keep the aircraft straight on the narrow runway. At around 35 knots, the tail came up and the view ahead improved markedly. At 55 knots, I was off the ground and accelerating to the best rate of climb speed of 65. It was not long after leaving terra firma that the fun began. The engine started to run like a dog, with lots of coughs and pops and a bit of shaking going on.

Luckily the surrounds of Cootamundra Airport are conveniently flat and relatively obstacle-free, so I set myself up for a straight-ahead landing while completing the emergency actions of changing tanks, checking the mixture was rich and magnetos were on BOTH. At this point the engine was still developing some power and the oil pressure was okay, so this bought me some time. With the ‘surprise’ element now partly under control, my mind went back 21 years and I began to wonder, ‘What if’? I gently eased the throttle back and waited to see what would happen. After a short wait the engine began to run smoothly and I decided a cautious return circuit was in order, with a plan B out-landing option firmly in view at all times.

While making my way around the circuit, congratulating myself on having sorted out the issue, my curiosity kicked in and I tried increasing the throttle setting to full power. Based on my brilliant deductive powers, I expected the engine to start running roughly again, confirming my diagnosis of ignition trouble. Instead, the engine was developing power like a trooper and showing no signs that any problem had ever occurred. What on earth was going on?

What was going on was what I now call an intergenerational technology trap. Anyone who learnt to fly in the 1950s has probably already figured out what happened to me and is having a quiet chuckle to themself. The answer to the riddle lies in the design of the carby heat system for the Gipsy Major engine.

The Gipsy is a notorious ice maker and can develop carburettor ice at almost anytime. To overcome this problem, some clever boffins came up with an air intake system that automatically runs the engine on hot air most of the time. The only time the engine doesn’t run on hot air is at full power, when a flap opens to let cold air into the carburettor to help the engine get to maximum horsepower.

Unlike modern aircraft, a Gipsy-powered aircraft needs the throttle setting to be reduced if carby ice is suspected on take-off. This closes the cold air intake and allows warm air to enter the induction system. The atmospheric conditions in Cootamundra that day were perfect for carby ice development and the big metal icemaker bolted to the front of my aeroplane was doing what came naturally (even at full power).

This incident has caused me much reflection over the ensuing years. I knew how the air intake system worked but being a product of learning to fly in the 1980s, I really only considered carby heat as part of the landing routine and occasionally as a taxiing issue (not a take-off consideration). If I had learnt to fly in a Tiger Moth or Chipmunk, I probably would have reduced power as a matter of course if the engine ran roughly after take-off. As a long-time Lycoming pilot, it entered my head only through ‘dumb luck’ because of a previous bad experience.

Lessons learnt

You may have trained on a modern aircraft with a glass cockpit, combined power levers or no mixture lever. Don’t fall victim to new intergenerational technology traps or, like me, have to rely on dumb luck. Think carefully about the systems you are about to step back to. If you are stepping down from a glass cockpit to a steam-driven cockpit, don’t forget that ‘instruments checked and set’ means you have to line up the DG with the magnetic compass. If you are stepping down into a complex 1990s aircraft, don’t forget there are now 2 ‘power’ levers and a mixture lever that is very important if you don’t want to run out of fuel.

We still fly in a time where they don’t make them like they used to.

Non-controlled operations

Non-controlled operations is one of the special topics on our Pilot safety hub. Refresh your knowledge.

Online extra

Don’t forget to check out the audio close calls. Hear the stories come to life.

Weather

Weather is one of the special topics on our Pilot safety hub. Refresh your knowledge.

Have you had a close call?

8 in 10 pilots say they learn best from other pilots and your narrow escape can be a valuable lesson. We invite you to share your experience to help us improve aviation safety, whatever your role.

Find out more and share your close call here.

Disclaimer

Close calls are contributed by readers like you. They are someone’s account of a real-life experience. We publish close calls so others can learn positive lessons from their stories, and to stimulate discussion. We do our best to verify the information but cannot guarantee it is free of mistakes or errors.