This is a story of ice. Not ice you put in a drink. Not ice that forms on an aircraft, but ice that can frighten and kill a pilot. You’ve got it – carburettor ice.

I have an ATPL, more than 3,000 hours and have owned a Cherokee 180 for over 20 years. I class myself as a safe and conscientious pilot, attending safety seminars and participating in safety webinars.

I have experienced carburettor ice twice in my aircraft in the last 2 decades but then as recently as twice within 2 days over the past month.

My first experience was after taking off from Sunshine Coast Airport in Winter on the first leg when flying the aircraft around Australia. Having had a new GPS installed, I spent considerable time with the aircraft idling while I attempted to set up the GPS for my flight to Cairns.

On take-off, the engine stopped at about 600 feet AGL! I immediately began to go through the engine failure checks but realised I would not complete them before impact with the ground.

The beach to my left looked good but was covered with people so I was contemplating a water ditching.

I remembered an instructor telling me that, if all failed with carby ice, you could make the engine backfire by quickly turning the magneto switch off and on. This is not in accordance with normal or emergency procedures but, with the prop windmilling, I tried it and the engine did start.

I gave a Pan call to the tower and landed safely, with a large red fire engine following me down the runway. (My passengers advised they would be taking a bus back to their hometown in NSW!)

After having the engine thoroughly inspected by a local LAME, we concluded that carburettor ice had caused the engine stoppage. They also advised a student pilot had crashed a Cessna 182 on final approach the week before, which was blamed on carburettor ice.

The next leg of our journey to Cairns was uneventful although I followed the beaches very closely!

Several years later, I again experienced carby ice while cruising over the water off Evans Head in Autumn. Application of carby heat solved the problem without much drama.

Up until a fortnight ago, and many years after those 2 incidents, carby ice had faded into insignificance while flying my aircraft. With the addition of a carburettor temperature gauge to the panel, I would have no trouble recognising the symptoms of carby ice before it became a major problem. Not so!

After recently taking off from my local airport, the engine began to run roughly at 1,500. My copilot (a retired RAAF Squadron Leader) thought we had hit a bird.

I immediately applied carby heat and returned to the airport. After landing we gave the engine a thorough ground run; the rough running disappeared and we put it down to a

fouled plug.

The following day and with a similar weather scenario to the previous day, the engine again ran roughly just after take-off. Carby heat was applied but the rough running became much worse! The local racecourse below looked a good option. As the application of carby heat had made the rough running worse, the carby heat knob was pushed back in. Big mistake! (See my explanation at the end.)

I struggled back to the airport with 60 knots indicated and the throttle pushed to the wall!

On consultation with my local maintenance shop, I was told, ‘You would have to be pretty unlucky to have carby ice on 2 days and 2 flights in a row.’ The consensus of opinion about the problem was fuel contamination.

However, after a thorough strip down of the carby (no fault found) and examination of fuel onboard (no contamination found), carby ice was indeed blamed as the culprit.

So be aware that carby ice can form at any time under the right conditions and often catch you as a pilot completely unaware. At low altitudes, it can be deadly. In the USA in 2023, the Federal Aviation Administration concluded 202 aircraft accidents were due to carburettor ice, resulting in 2 fatalities.

Lessons learnt

Thoroughly understand correct procedures in an emergency. It was a natural reaction to push the carby heat knob back in when pulling it out had made the situation worse. However, later research has told me it may take as long as 2 minutes for the engine to ingest the water from the melted ice and resume normal running. During this time the engine roughness will get worse before it gets better!

My trusty carby temp gauge indicated the likelihood of carby ice on these 2 flights was low.

Don’t rely completely on one source of information to the detriment of others.

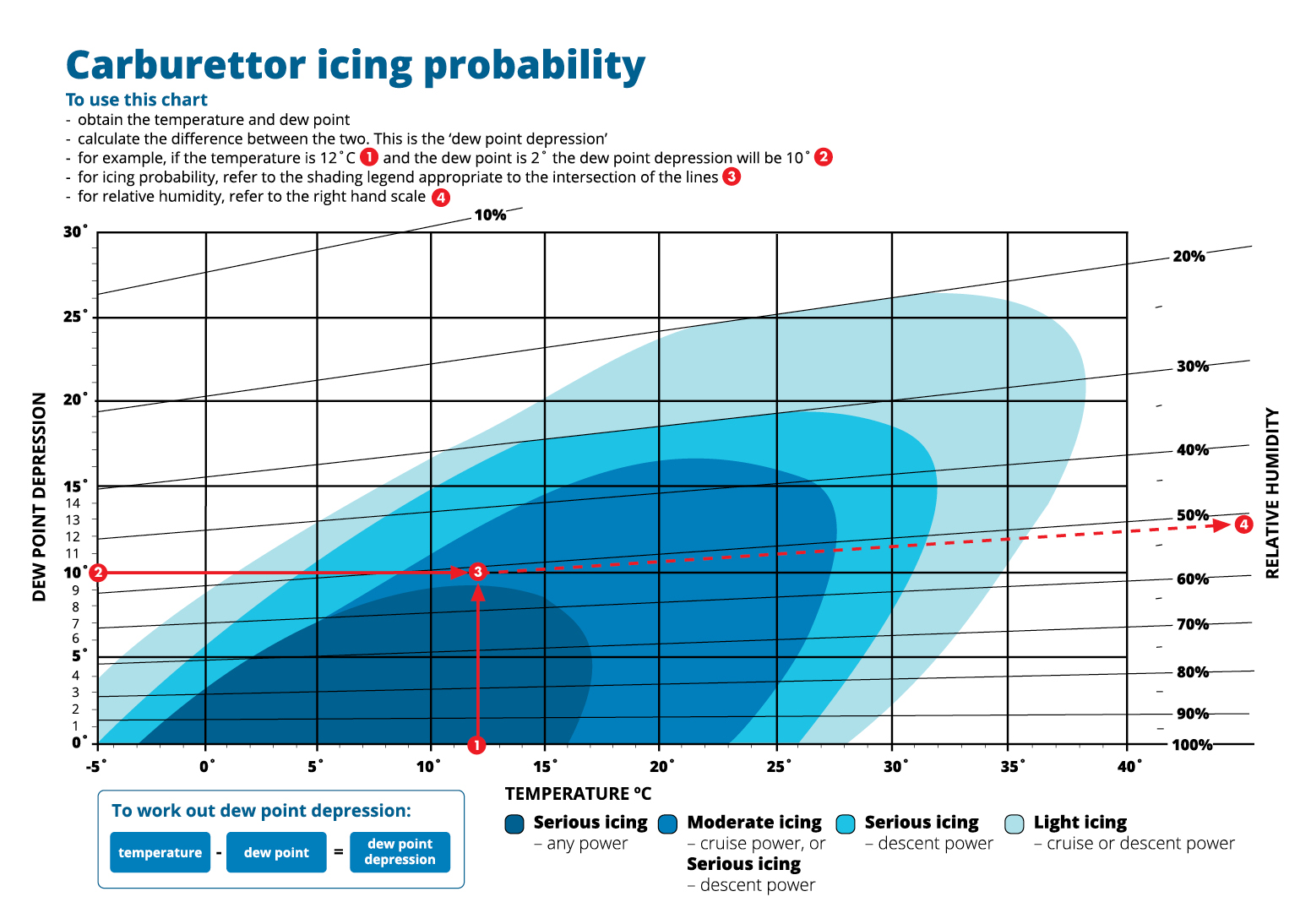

Use the CASA icing chart before a flight if you think carby ice may be a problem.

Crew resource management should apply to every flight. Be prepared for an emergency at any time.

You’re never too old to learn.

Online extra

Don’t forget to check out the audio close calls. Hear the stories come to life.

Weather

Weather is one of the special topics on our Pilot safety hub. Refresh your knowledge.

Have you had a close call?

8 in 10 pilots say they learn best from other pilots and your narrow escape can be a valuable lesson. We invite you to share your experience to help us improve aviation safety, whatever your role.

Find out more and share your close call here.

Disclaimer

Close calls are contributed by readers like you. They are someone’s account of a real-life experience. We publish close calls so others can learn positive lessons from their stories, and to stimulate discussion. We do our best to verify the information but cannot guarantee it is free of mistakes or errors.