Most pilots know that low flying, particularly below 500 feet, is not only dangerous but is in most cases, prohibited.

When it comes to understanding the risks, Frank Drinan is about as well versed as they come. A second-generation agricultural pilot, Frank has amassed more than 8,000 hours of flight time and runs Keyland Air Services, an aerial application operation based in Dalby, Queensland.

Frank’s message is a simple one, ‘Leave it to the professionals.’

In the context of how risk managed these operations are, it’s easy to understand why trying low flying on a whim, without training, is never a good idea. Low flying carries – obstacles, increased turbulence and potentially, other low-flying aircraft such as remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPAS) or drones. It also dramatically curtails available options in an emergency, such as an engine failure or power loss.

Frank is also president of the Aerial Application Association of Australia whose membership represents more than 90% of aerial application aircraft in Australia.

The association has an active role in training the next generation and Frank quickly identifies that managing the risks of low flying starts with quality training. New ag pilots are, after gaining a commercial pilot licence, under more than 40 hours of training just to get an aerial application rating, the basic qualification that permits low flying for application of various products to crops and agriculture.

But it’s what happens next that is a textbook lesson for anyone considering low flying.

Learning continues after the rating. ‘It’s a controlled environment for new pilots, even after the 40 hours of training,’ Frank says. ‘To get to be unsupervised ag pilot – it’s then a minimum of 110 hours of supervision on the job.’

Risk management is fundamental to this type of flying. ‘Even as experienced ag pilots, we’re not going out and jumping straight into a paddock. We’ve got a safety management process, and there’s a risk assessment done at the base before the job even gets to a pilot.’

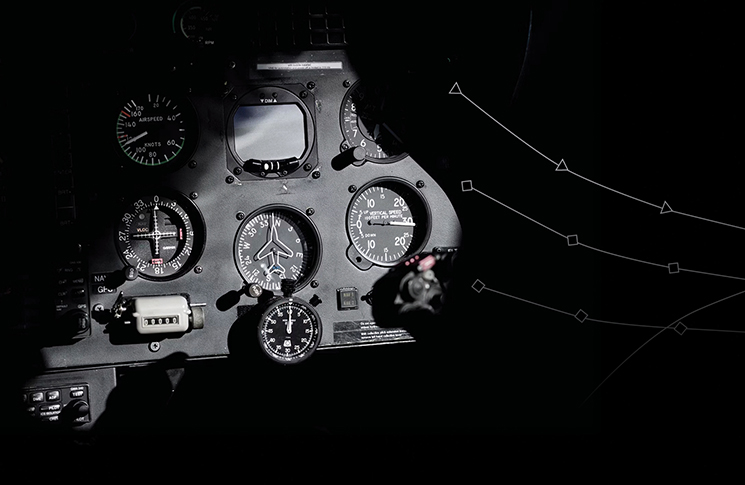

On location, this process continues. ‘When we get to the paddock, we’ve got a map of the site which will include hazards like powerlines and towers,’ Frank says. ‘Then the pre-application checklist and inspection is conducted to identify those and any other hazards in the paddock. We might do 2 or 3 inspection orbits before starting our first run. It’s a very structured approach to the job.’

CASR 91.265 and 91.267 essentially set the floor at 1, 000 feet AGL for flight over a populous area and 500 feet AGL otherwise. Both regulations go on to set out limited circumstances where flight below these heights is acceptable – take-off, landing, certain training or if you have the appropriate approvals and ratings to fly lower.

‘If you’ve got someone with a PPL (private pilot licence) that thinks it’s a great idea to beat up (does a low pass over) at low level – they’re going into unchartered territory,’ Frank says.

‘You see it time and time again. So many people overextend their capabilities to do stupid things. It ends up in tragedy, and it’s not just them. It’s the other people on board. It’s the family, it’s the community. It’s just not worth it.’

Frank hits on a misconception that ag pilots are doing low flying for the sake of it. ‘If one of our pilots goes and beats up a tractor, as an example, they’re out the door,’ he says. ‘That’s not even a risk that we take, and we’re out flying low every single day.’

Non-controlled operations is one of the special topics on our Pilot safety hub.

A well written article and wise words from Mr Frank Drinan. I flew my share of Low Level Day and Night, as well as in formation, flying Bell Iroquois UH-1 helicopters for the US Army. Imagine flying below 500 feet, downwind, over terrain that would be considered the exact opposite of an airfield -and, your engine quits due to fuel exhaustion or mechanical failure . . .

I was prepositioning a Beechcraft Sierra, about 1980, for an Instrument Checkride, the following morning. I was flying with my Instructor, Army Major Al Friend, to get one last Non-precision Approach practice and familiarisation with that particular aircraft, as I had done all of my Instrument training in a Beechcraft Duchess. The aircraft was topped off with AvGas and preflight briefing and inspection was done at Fritzsche Army Air Field, Fort Ord, California. It would be a short flight. Whilst we were on final approach over Monterey Bay to Monterey Peninsula Airport (as it was known), the engine became rough and began to sputter. We became instantly aware we could become wet and got busy adjusting power, checking the correct position of the fuel valve, fuel boost pump On, Magnetos On, and advising ATC. Major Al Friend, worked his magic to get a surge of thrust and the beach was in site, but the engine faltered again. Another flurry of activity and a surge of power and we were over the golf course at the end of the runway. But, the engine was struggling to continue running, again. More activity, and one last surge of thrust and we made it over the runway 10R threshold, though the engine finally quit. Major Friend and I had to push the Beechcraft Sierra from the runway to parking. As it turned out the Fuel Pump had failed.

What if I was over-confident, reject authority, didn’t comply with the Regulations, just a cowboy, and decided to take a low level joy flight over the beach or just off shore, Solo, that day? I would have become another statistic for the NTSB and I would have enjoyed a very short-lived career as a pilot.

Think of the consequences, do whatever it takes to protect your pilot licence, every time you take to the sky.