The malfunction of a flight instrument was only one link in a chain of shortcomings that turned a cargo aircraft into a winter inferno.

Boeing 747-2B5F, HL7451

Hatfield Forest, Essex, UK

6:38 pm, Friday 22 December 1999

Glass traps open and close on night flights. The Walker Brothers, 1978

There is a corner of an English field that is forever Korean. That richer dust concealed is where Korean Air Cargo flight 8509 crashed less than 2 minutes after taking off from London Stansted Airport.

The air story

The final hour in the lives of captain Park Duk-kyu, 57, first officer Yoon Ki-sik, 33, flight engineer Park Hoon-kyu, 38, and 45-year-old ground engineer Kim Il-suk had been tedious and frustrating. First, the crew had called the wrong frequency for pushback clearance – Stansted Delivery operated only in peak periods, which that dark, windy and rainy December evening certainly was not.

After a two-minute delay they called Stansted Ground only to be told no flight plan had been filed. There was more waiting, as they phoned their ground handler to get the paperwork underway. The pushback tug that appeared 46 minutes after their first call broke down halfway through its run, then there was a delay finding a marshalling car to guide them to the taxiway centreline.

Captain Park took over radio calls during pushback, diverging from standard operating procedure, which delegated these to the first officer while the aircraft was on the ground. He sounds to have been in a tetchy mood, venting to the first officer several times in what the UK Air Accidents Investigation Board (AAIB) report delicately described as ‘inappropriate cross-cockpit comments’.

Finally taxiing, the captain noticed the distance measuring equipment (DME) was not indicating correctly. This was significant because the flight plan called for a left turn soon after take-off, at 1.5 nm DME. This was to comply with noise restrictions so as not to antagonise residents of the nearby village of Great Hallingbury (who, as things turned out, were soon to be assaulted by noise like nothing they had experienced before). An inconclusive conversation ended when the flight engineer said, ‘Now it’s working correctly.’

At 6:35 pm, more than an hour after the first call, they finally heard the words from Stansted Tower, ‘Line up and wait runway two three.’

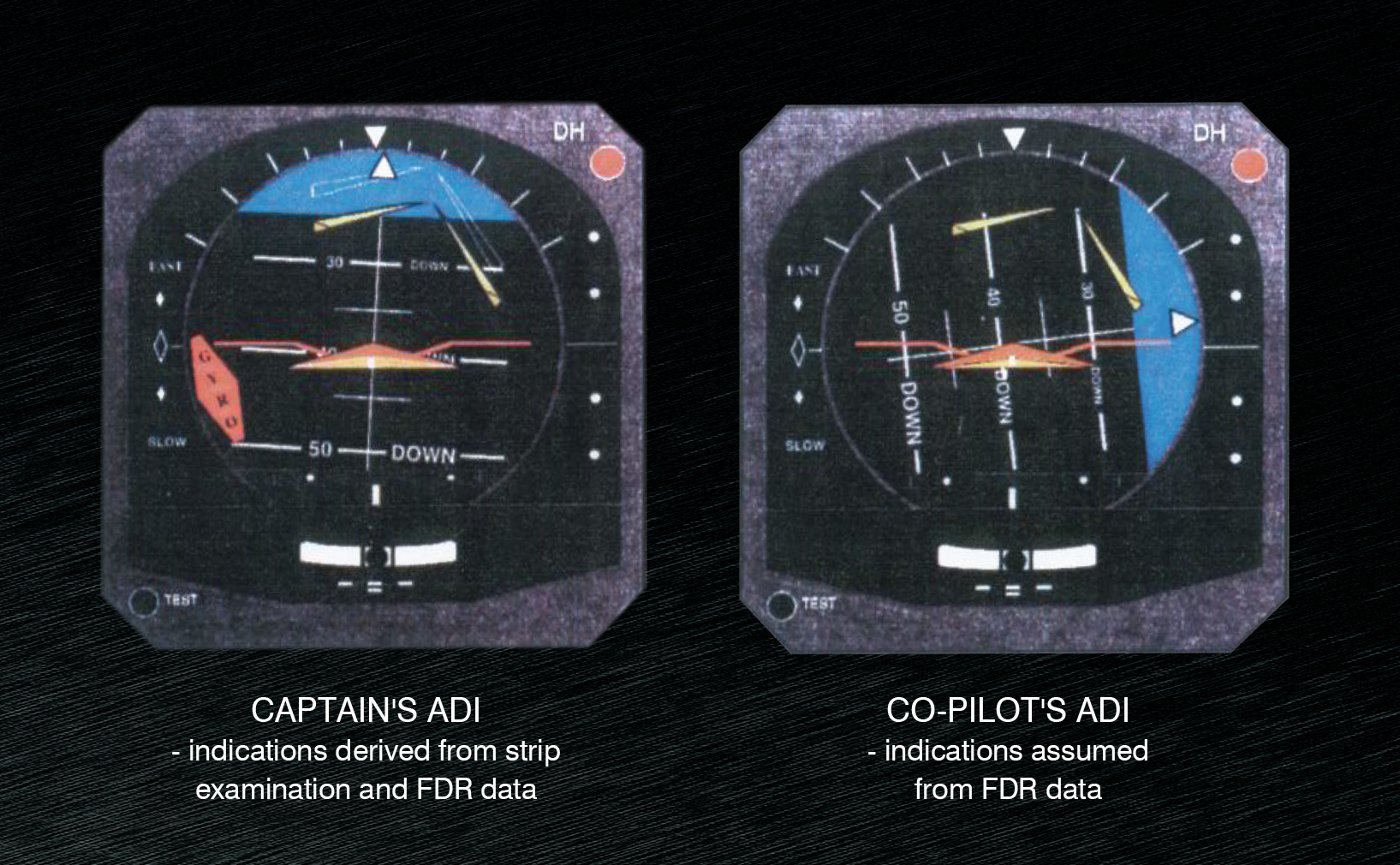

Take-off was routine, with a prompt ‘gear-up’ said in English shortly before entering cloud at 400 feet AGL. But eight seconds later, the captain said in Korean, ‘I didn’t expect this.’ It is unclear what this remark meant. A few seconds later he restated they needed to turn at 1.5 nm DME, before declaring the system was not working. As they passed through turbulence, an instrument comparator warning chime sounded twice, about the same time as these 2 utterances. Its purpose was to alert a difference in indications between the captain’s and first officer’s attitude direction indicators (ADI).

The first officer announced their new heading which, after an expression of confusion from the captain, he had to repeat. About 5 seconds later, the comparator alarm sounded again and just under 4 seconds after that, the flight engineer said in Korean, ‘The bank is not accepting.’ The flight data recorder (FDR) recovered later that night revealed a bank angle of 46.5 degrees at this moment.

Four seconds later the flight engineer repeated his warning, this time in English, ‘Bank, bank!’ There was no reply from the captain for 5 seconds. Then he uttered a Korean expression translated as, ‘Eh you’. Reverting to Korean, the flight engineer said, ‘Standby indicator also not working’, again to no reply. Instead, the captain said, ‘Request radar vector,’ followed by another, ‘Eh you’.

The flight data recorder (FDR) recovered later that night revealed a bank angle of 46.5 degrees at this moment.

The comparator warning continued for 10 chimes before ending abruptly. The official report reaches a disquieting conclusion: ‘The cancellation mid-tone suggested the warning was cancelled by the crew.’

As bank angle passed through 80 degrees and wind noise rose on the flight deck, the flight engineer spoke for the final time, in Korean. From the report: ‘His last remark before impact also contained the word “bank” and appeared to be said with resignation for what was about to happen.’

Impact

Several people looking east from Great Hallingbury saw the 747 falling in planform – as if viewed from below – due to the extreme bank. Seconds later the lights in the village went out as the aircraft’s wing clipped power lines before its crash created a crater 43 metres across and 3.5 metres deep. A contemporary newspaper report says, ‘Witnesses reported a vast orange fireball, and debris was seen falling on to roads and the surrounding areas.’

The ground story

The captain’s ADI had indeed frozen, as the flight engineer pointed out. In response to the faulty instrument, the captain had increased bank and flown the aircraft into the ground. A left roll command was maintained until impact.

But this was the second time the ADI had frozen that day. The aircraft’s previous flight had been to Stansted from Tashkent, capital of Uzbekistan. On the climb out of Tashkent, in day VFR, the aircraft commander (a different captain) had noticed the ADI horizon stuck at 15 degrees as he rolled the aircraft. The comparator alarm sounded and the captain, in line with procedure, had handed control to the first officer. The problem appeared to be not in the instrument but in the inertial navigation unit (INU) that supplied data to it. Selecting ALT, to change the information source for the captain’s ADI to another of the 747’s 3 INUs, restored the display and the captain continued the flight.

The inbound flight engineer used the Boeing fault reporting manual to identify and codify the failure, which he also wrote into the aircraft’s technical log.

At Stansted a contracted British engineer and Korean ground engineer Kim worked on the aircraft. They divided the duties between themselves and, at Kim’s request, the other engineer removed the captain’s side ADI. Kim noticed a damaged connector pin on the instrument. The British engineer, who was not qualified in avionics, summoned a colleague at Kim’s request to fix this. The second British engineer, summoned to perform a specific act rather than diagnose a problem, repaired the connector pin, activated the INUs and performed a self-test on the instrument, which passed.

In response to the faulty instrument, the captain had increased bank and flown the aircraft into the ground.

At no time was the fault isolation manual (an engineer’s expanded version of the fault reporting manual) used. The nearest copy possessed by Korean Air was in Moscow, where Kim was based. Had it been consulted, it would have said unequivocally that the listed fault lay in the INU, not in the instrument which was merely its display.

Soon after 4:30 pm, the outbound crew arrived. They had been in the United Kingdom for 48 hours, most of it spent in a hotel near the airport. They did not meet the inbound crew, but the inbound flight engineer had briefed the ground engineer Kim about the problem, emphasising the fault lay in the INU. It is unknown whether Kim made any mention of the instrument problem to his fellow crew members. And it is unknown what Kim wrote in the aircraft’s technical log because, against procedure, he carried this with him when he boarded the aircraft for the flight to Milan in Italy.

Analysis

The crash raised several fundamental safety questions: why did the captain follow an instrument showing a reading at odds with the dials that surrounded it, why had the captain and first officer ignored the warnings of the comparator alarm and the flight engineer and why was a known problem on the inbound flight not repaired at Stansted?

The captain’s 13,490 hours may have worked against him. ‘Pilots are taught to believe their instruments,’ the report says. ‘When the ADI did fail, he was apparently not able to recognise the problem, because his primary frame of reference had always been through his visual interpretation of the ADI attitude display.’

The AAIB considered incapacitation of the captain as a possible explanation for his lack of response to the audio and visual warnings, calls from the flight engineer and the divergent aircraft attitude. It concluded, ‘The movement of the control wheel and comments from the commander about navigation which continue up to a few seconds before impact indicate that he remained conscious and active.’

Obvious incapacitation can be ruled out based on the CVR and FDR evidence but subtle incapacitation is harder to eliminate. As Eurocontrol’s SKYbrary defines it, subtle incapacitation can involve skills or judgement being lost with no outward sign. ‘The victim may not respond to stimulus, may make illogical decisions, or may appear to be manipulating controls in an ineffective or hazardous manner.’

Anyone who has ever suffered transient circadian rhythm upset – jetlag – knows the fatigue involved in operating in a different time zone can easily meet the threshold for subtle incapacitation. The accident flight crew had been in the UK for 2 of the northern hemisphere’s shortest days, with limited opportunity for their body regulating pineal glands to reset from exposure to sunshine.

Seoul time, 9 hours ahead of London time, would have placed the short flight’s end at 3:38 am, in the window of circadian low if the crew members were still internally operating in their home time zone. Grumpiness, as amply demonstrated by the captain, can certainly be a symptom of fatigue, as can the passivity of the first officer, but this is as far as speculation can go. There is no ‘smoking gun’ to conclusively implicate circadian upset. Destruction of the crash scene meant, ‘It was not possible to determine if there was any evidence of any pre-existing disease, alcohol, drugs or any toxic substance that may have contributed to the cause of the accident.’

The other possible cause of communications breakdown was cultural. Cockpit gradient is a term used to describe the potentially hazardous imbalance between an experienced senior crew member and an inexperienced subordinate. A steep cockpit gradient inhibits the subordinate from alerting the senior to an error, it is argued.

Science writer Malcolm Gladwell ran with this line in one of his popular books, arguing that Korea’s hierarchical culture and subtle, suggestive language were implicated in the breakdown of communications. CASA Flight Simulation Leader John Frearson, who flew as a senior pilot with Korean Air for 11 years, finds Gladwell’s analysis simplistic and potentially misleading. For one thing, the flight’s operational communication was largely in English.

It’s important not to be derogatory of Korean or military culture because these types of accidents are found in many cultural backgrounds, Frearson says.

He cautions that a flat cockpit gradient can be as treacherous as a steep one. ‘There are 2 ways of you not clueing in on what I the pilot am doing,’ he says. ‘One, because you’re a colleague, a friend of equal rank, and you think it’s a bit demeaning to me for you to speak up. The other is if you’re scared to speak up because you only have a few hours and you bow in deference.’

Frearson refers to the Qantas flight QF1 landing accident that happened at Bangkok 3 months before the flight 8509 crash. The breakdown of flight deck communication during landing roll was one factor in an expensive and embarrassing accident. ‘As we saw with Qantas at Bangkok, a guy from an Australian culture, with a strong union and an impressive seniority number was unable to say, “Mate, what are you doing?”,’ Frearson says.

He joined Korean Air in 1996 as one of many foreign pilots hired to help with the airline’s expansion and assist in rebuilding the organisation’s safety culture. Three years before Stansted, this was freely acknowledged to be a problem.

As we saw with Qantas at Bangkok, a guy from an Australian culture, with a strong union and an impressive seniority number was unable to say, ‘Mate, what are you doing?’

‘The company was on the edge of the precipice regarding their regulators, codeshare partners, insurers and public image,’ he says. ‘They appointed 2 pilots on each fleet to conduct high-risk situation training for their crews. I was appointed for the [McDonnell Douglas] MD-80.’

Frearson and others worked subtly to break down cultural divides on the flight deck. On simulator sessions he would insist the captain and first officer shake hands before the lesson began. ‘We’d typically have a meal together before the session and I’d emphasise the lesson would be about “what’s right, not who’s right”.’ He was also unafraid to evoke emotion in the service of safety. Several times he froze a simulator in desperate straits and told the pilots, ‘Now another man will walk your daughter to her wedding,’ sometimes to shattering effect.

He began to be impressed by the diligence of the Korean pilots and their humility in accepting advice from outsiders. ‘There was a feeling that we were starting to move beyond the accidents at Gimpo [runway overrun, 1998] and Guam [controlled flight into terrain, 1997]. Then came Stansted, which created shock, horror and the realisation that something was very wrong.’

In early January 2000 Frearson was summoned to head office and promoted. ‘After Stansted, management was appointing expatriate deputies in every area,’ he says.

We had monthly safety meetings that were about owning up to stuff-ups.

One other factor changed after Stansted. ‘The company built sophisticated flight data analysis and quality assurance programs that became the eyes and ears of fleet chief pilots,’ Frearson says. ‘You could actually see what crews were doing.’ This led to a new level of frankness and accountability. ‘We could see we had a high proportion of unstabilised approaches at some airports. And we had monthly safety meetings that were about owning up to stuff-ups.’

Gradually change occurred. A survey of Korean Air pilots in May 1999 had found, ‘Flight crews as a whole preferred the “captain-centred” methodology of flight deck operation, with a relatively greater reliance on the captain,’ the AAIB said. However, a follow-up survey in 2002 found an observable change in the crews’ response.

The maintenance aspects of the Stansted crash came more as a surprise. ‘Korean Air maintenance at Seoul or Busan was a byword for excellence,’ Frearson says. Maintenance at Stanstead was not carried out by Korean Air, but by a British subcontractor. An airline representative’s signature was needed whenever an aircraft was returned to service and this was the role of ground engineer Kim. Drift from this arrangement had contributed to the splitting of repair from diagnosis and, by removing confirmation and oversight from the repair process, had allowed biases and oversights to go unexamined. The Korean and British engineers made assumptions about each other’s competency that went untested.

Other than printer cartridges destined for Milan that still litter the ground, there is no memorial to flight 8509 in Hatfield Forest. The crew of the largest aeroplane to crash in the British Isles are forgotten by all except those who knew and loved them. The AAIB report is their last testament, a technical document but also a kind of ghost story in which the doomed enact a tragedy that cries out to be remembered.