In September last year, the Bureau of Meteorology declared 2023/2024 to be an El Nino year, with higher-than-average temperatures and drier air, and less rain. The past few years under La Nina have seen vegetation grow, and in combination with these warm conditions, they create a perfect storm for bushfire activity.

Although most of the country has had a wet start to the summer season, we are by no means out of the woods just yet. El Nino conditions continue to prevail, which could mean significant bushfire activity in the latter part of the season.

The Black Summer bushfires of 2019/2020 taught us important lessons about fire-borne weather patterns and their effect on the aviation industry, particularly the impact of pyrocumulonimbus clouds.

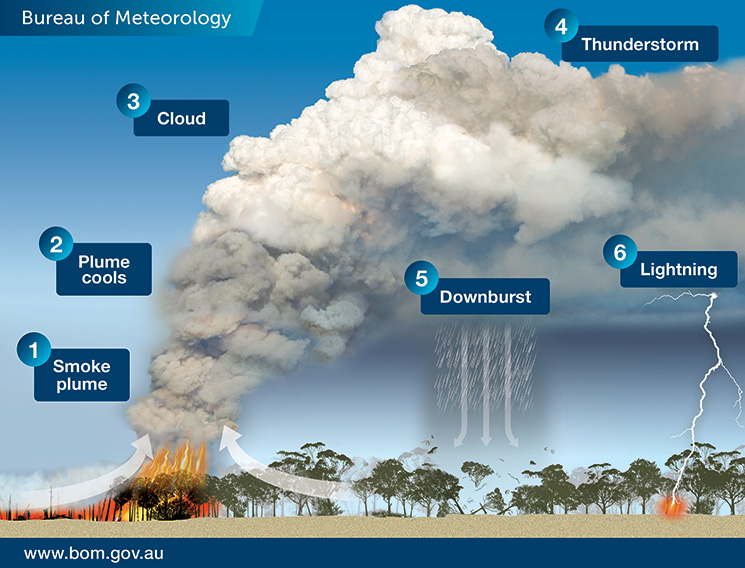

Under the right circumstances, pyrocumulous clouds form when intensely heated air from bushfires rises into the sky, cools, and condensation from existing atmospheric moisture and moisture evaporated from burnt vegetation combine with ash particles.

The Bureau of Meteorology says bushfires can create their own weather. ‘[Pyrocumulonimbus clouds] are a thunderstorm that forms in the smoke plume of a fire (or nuclear bomb blast or volcanic ash cloud),’ the bureau says. ‘In Australia, they most commonly form in large and intense bushfire smoke plumes.

‘As the plume rises to higher and higher elevations, the atmospheric pressure reduces, causing the plume air to expand and cool … If it cools enough, the moisture in the plume air will condense and forms cumulus cloud which, because it comes from the fire plume, we call “pyrocumulus”.

‘Further expansion and cooling cause more moisture to condense and the cloud air to accelerate upwards even more … Having produced a thunderstorm, the cloud is now known as “pyrocumulonimbus”.’

During the height of the Black Summer bushfires a Qantas flight from Melbourne to Canberra unexpectedly encountered turbulence from a fire-generated weather system.

Aviation Safety Advisor Craig Peterson, an experienced pilot, says weather radar on aircraft may not detect fire-generated turbulence because it is not always associated with high levels of water and the radar typically does not detect small ash particles.

‘Turbulence in and near pyrocumulus clouds can effectively be like clear air turbulence,’ he says.

While GA pilots would be aware of the turbulence and reduced visibility associated with pyrocumulus clouds, they may not be aware of other hazards, Peterson says.

‘If you do fly near them, you are likely to encounter the firebombing aircraft and their spotters,’ he says. ‘People forget those aircraft might be operating in the vicinity of pyrocumulus for water bombing operations.

‘The other danger that a lot of people don’t realise is that fires attract birds. The fire disturbs insects, so you get clouds of insects airborne and the birds come to feed on them. So, close to a pyrocumulus cloud, you’re typically going to see a lot of bird activity as well which presents a hazard for aircraft.’

Peterson says pyrocumulonimbus clouds can be difficult to see through smoke haze. ‘It’s a bit like what we call embedded thunderstorms – the cumuliform cloud associated with the thunderstorm, or in this case the fire, can actually be embedded in poor visibility due to smoke haze,’ he says.

‘So if a pilot was flying along in nice blue skies and they saw a big pyrocumulus in front of them, they would avoid it because they know it’s got to have turbulence in it, they don’t have to use the weather radar to know that. However, if they are flying in hazy poor visibility conditions and can’t see ahead, the pyrocumulus could be sitting in all that murk and they just go straight into it because the weather radar may not tell them it’s there.’

Since the Black Summer fires, major airlines are becoming more cautious and are deciding to cancel some flights where numerous bushfires are burning at the same time, in an effort to reduce the risk of sustaining damage from turbulence created by a pyrocumulonimbus cloud.

General and recreational aviation pilots should plan their flights to avoid bushfires altogether. However, if pilots spot smoke while in flight, they should remain at least 5 nm and 3,000 ft away from the fire boundary at all times and report the sighting to their local fire authority.

Additional information: How fires make thunderstorms (bom.gov.au)