Are you a Part 121, 133 or 135 operator and undertaking a risk assessment of your business?

Are you finding developing a scalable and fit-for-purpose safety management system challenging? Don’t worry, you’re not alone.

For smaller operators, starting a safety risk analysis from scratch can be daunting.

In aviation safety management, several risk analysis models can be used to identify hazards and determine the likelihood and severity of risk associated with that hazard. So many models that it can become confusing. You might have heard phrases like ‘Swiss cheese’, ‘5M’ and ‘JSA’ bounce around, for instance.

One model is the bowtie. It looks exactly what it sounds like – a formal bowtie. Like the Swiss cheese accident causation model, it prescribes various layers (known as barriers) to stop hazards getting through and causing an accident.

CASA has consulted with industry and has developed a series of risk analysis bowties around ICAO’s High-risk Categories of Occurrence (HRCs), with a focus on the regulatory controls as the barriers that you can use to develop a workable SMS for your organisation. The categories are:

- loss of control inflight

- controlled flight into terrain

- mid-air collision

- runway incursion

- runway excursion.

Human performance, technical and organisational factor bowties have also been developed in support these categories.

The bowtie model has an interesting origin story. First formally used in course notes in 1979 at the University of Queensland to analyse hazards within the chemical industry, the model was soon adopted by large companies like the Shell Oil Group.

The ease of using the bowtie model became so influential that it began to expand outside the petrochemical industry and into other operational sectors such as aviation, maritime and healthcare.

But enough about its history. Here’s how they work.

Atop the bowtie model sits an identified hazard, for instance, flying an aeroplane.

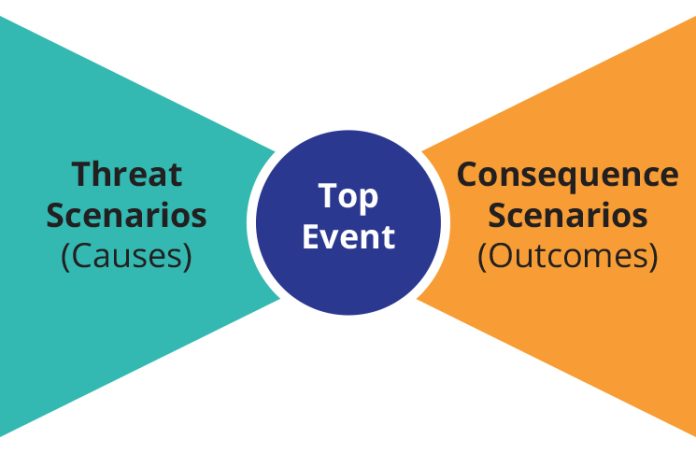

Extending from the hazard is a top event. In this context, the top event describes when control is lost over the hazard, which could be several things, like an onboard fire, aircraft losing altitude, pilot incapacitation or a dangerous goods leak in the hold.

From there, the bowtie extends out to the left-hand side with a series of threats associated with the top event, for instance, the inhalation of smoke, loss of control or pilot drifting into a microsleep.

Extending to the right-hand side are a series of consequences related to the top event, such as asphyxiation, injuries to passengers or crashing the aircraft.

Each threat and consequence can be extended into a series of barriers, preventative or recovery. These are mitigating factors that prevent the top event and consequences occurring. Barriers are the ‘Swiss cheese’ of the bowtie model.

Once the bowtie is fully extended, the diagram records the results of the analysis by forming a comprehensive picture on a page of all the factors that could lead to damage or loss.

Bowtie models are designed to be dynamic and interactive, and can be built using platforms such as BowTieXP and BowTie Pro. The software allows you to expand and retract the individual levels of the bowtie, so you can include as much or as little detail as you like.

To get you started, download the bowties for Part 121, 135 and 133 operators from the CASA website.

CASA will be releasing further bowties for aerial firefighting, aerodromes, business aviation, ballooning and parachuting in the coming months.

To learn more about risk analysis bowties and safety risk management, visit the CASA website.

Does re-inventing the wheel make it rounder or have less rolling resistance?

For any AOC Holder to first place to start is a well-written and formatted Standard Operating Procedure that always points to and highlights regulatory compliance.

The second place to start is a management team that actually care about aviation safety and actually mean what they say, when talking up aviation safety.

The next on the list of must haves is, ground and flight crew whom respect and comply with the aviation regulations and AOC Holder’s SOP. Pilots must appreciate that their Pilot Licence is a privilege that comes with great responsibility and they have a duty of care to their passengers, fellow employees, ground crew working near their aircraft, and the general public.

And, another safety net is Crew Resource Management, Threat Error Management or whatever you want to call it, tomorrow. Not enough pilots of single pilot, single engine aircraft, for instance see the value of CRM and/or TEM, perhaps because the terminology does not gel with them. Perhaps it should be: “Threats and Error Mitigation Strategies and Cockpit Resource Management”. Imagine where you locate your torch/flashlight, at night, so it could be easily accessed, turned on, and held in a position to illuminate the instrument panel, in the event of an electrical failure would be part of the aforementioned title proposed. Is the torch/flashlight a resource? Indeed it is. Would easily assessing it and using it, whilst controlling the aircraft, in the event of an electrical failure at night mitigate a threat to safety of flight? Indeed it would.

So, rather than re-inventing the wheel that has been tried and true for the past 5,000 years, we need to apply what we already know consistently and diligently. Whether you call it the “Swiss Cheese Model” or the “Bowtie Model”, but still do the same ol’ dumb stuff with the same mentality, “It can’t happen to me” or “I know better”, then you are simply doomed to repeat others’ mistakes and maybe with fatalities, as an outcome.

That said, CASA needs to take a long hard look at itself as part of the Threat and Error mitigation strategy, instead of enabling bad outcomes. On 29 December 2014, there was a fatal aircraft collision with water, by a Cessna 172S. ATSB found, “The Civil Aviation Safety Authority had issued the operator with a dispensation that permitted low-level flight down to 150 ft above obstacles”. Consider this was for a low experienced pilot, flying a single engine Cessna, so far out to sea it could not safely glide bad to shore, should the engine quit. And, that is only one fatal aircraft accident I can point to where CASA bears some responsibility, whether they want to acknowledge it or not. And, it is not about making the regulations more verbose, harder to manage or more prescriptive. That has not worked, so far.

As a professional pilot of 36 years experience, I only ever cared about doing whatever it took to protect my pilot licence. It did not make me popular, yet I reached the pinnacle of my aviation career as a captain of Boeing 747-400 jumbo jets, in spite of myself.