It remains the most deadly aircraft crash on Australian soil, yet is largely unknown outside the town where it happened.

Boeing B-17C, 40-2072, VH-CBA

Bakers Creek, Qld

6:02 am, Monday, 14 June 1943

‘In times of war, the law falls silent.’ – Cicero

They came from the valleys of West Virginia and the high plains of Colorado, the snows of North Dakota and the subtropics of Florida. They abandoned their lives in blackened industrial conurbations and dusty one-horse towns to fight against the brutal empires of Nazi Germany and Japan.

More than 8,000 Americans served alongside Australians in the New Guinea campaign. Mackay, on the central Queensland coast, became a rest and recreation centre for the US armed forces. Priority for the 10-day reprieve was given to front-line troops.

Gavin Souter, 14 in 1943, remembers the politeness and generosity of the American soldiers who came to his bank manager father’s house for Sunday dinner in their grasshopper-brown uniforms. ‘The Americans were courteous, friendly and free-handed with Saturday Evening Posts, Hershey bars and Chiclets (chewing gum),’ he wrote in his memoir, The idle hill of summer. One astonished the family at a church service by putting a pound note into the collection basket.

Early on the morning of 14 June 1943, 35 American soldiers were preparing to return to the front line after 10 days of rest and recreation in Mackay. Their transport back to war was a US Army Air Forces Boeing B-17C of the 46th Troop Carrier Squadron that carried an Australian civil registration to satisfy the bureaucratic imperatives of joint command. They took their seats around the radio operator’s compartment and fuselage of the converted bomber.

The US Army kept the crash officially secret until 1958.

About 6 am the aircraft took off into ground fog on runway 23 of what is now Mackay Airport. Normally the flight would have climbed to 500 feet before making the first of a series of turns that would bring it over the field to establish a dead reckoning start point. This morning it climbed to only about half that height, witnesses said, before making the first of 2 left turns.

A second turn brought it on to a roughly reciprocal heading with the runway, but by now the aircraft was descending with a slow, implacable sink rate. It hit the ground, wings level, in a woodland near Bakers Creek, south of the town. The crew of 6 and all but one of the passengers were killed.

The temptation to see for himself was too much for the aircraft-obsessed Souter to resist. The next day he evaded a perimeter guard and struck out through the bush.

‘I noticed that the tops of all the trees around me had been lopped, at first only a few feet from the top, and then progressively lower as I moved cautiously ahead,’ he recalls.

‘Then suddenly there were no trees at all – just an open swathe of bare ground about the width of a Flying Fortress and about a hundred yards long.’

Secrecy and blame

One of Professor Robert S Cutler’s enduring memories of his father was the older man’s distrust of air travel. ‘He’d say things like “Always sit up the back of an airplane” without any explanation,’ Cutler says. In 1999 when Cutler, now of George Washington University, was sorting his late father’s belongings, the reason for this morbid caution became clear. Captain Samuel Cutler had been stationed at Mackay during World War II and one of his duties had been to shut the fuselage door after the B-17 was loaded. Later that day he saw the crash site, which haunted him the rest of his life.

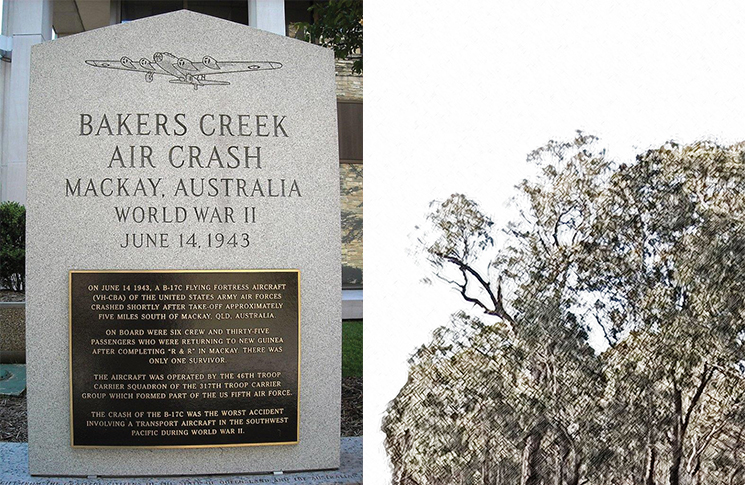

Robert Cutler made inquiries about the crash mentioned in his father’s diary and found there was no military record of it. Wartime censorship meant only the people of Mackay had any knowledge of the disaster until VJ Day in 1945. The US Army kept the crash officially secret until 1958. Next of kin were told only their loved one had died ‘somewhere in the south-west Pacific’. Cutler’s efforts were spurred by this official oversight and, with Mackay historian Col Benson, he succeeded in having memorials for the crash constructed in Mackay and in Arlington National Cemetery, near Washington D.C.

Analysis

As part of his 2003 book on the crash, Mackay’s flying fortress, Cutler contacted 3 former crew chiefs from the 46th Troop Carrier Squadron. Not satisfied with the explanation ‘pilot error’ which appeared in the only official report on the crash, compiled by the Queensland police, he discussed possible scenarios and factors with the veterans. Four possible and interlocking explanations emerged:

- aircraft

- engines

- loading

- crew performance.

Aircraft

The B-17C 40-2072 was a combat veteran. It had been sent to the Philippines in 1941, before the US entered the war and was one of a handful of American aircraft to escape destruction when Japan attacked the US base at Clark Field, Manilla, on 8 December 1941. It was flown to Australia and made a raid on the Japanese occupied airfield at Davao in the southern Philippines. After dropping its bombs, it was involved in a harrowing running air battle on the return flight to Australia. There were more than 1,100 bullet holes in the airframe.

Despite the damage, it was repaired and served in 1942 and 1943 as a military transport in Australia. One of its pilots flew it under the Sydney Harbour Bridge. By 1943 it was stationed in Mackay where it acquired a new name – engineers called it ‘Miss EMF’, standing for ‘every morning fixit’. ‘For every 8 hours of flight, we spent almost 8 to 10 hours on maintenance,’ a crew chief said.

It acquired a new name – engineers called it ‘Miss EMF’, standing for ‘every morning fixit’.

The aircraft had been out of service for 4 weeks before its final flight. During this time, it received a new fuel tank and 2 new engines. It made a successful test flight the day before it crashed.

Engines

Engines could have contributed to the destruction of the aircraft in 2 ways – by fire, by the more insidious means of partial power loss, or by a combination of both. Contemporary reports described the aircraft as being on fire but witnesses who corresponded with one of the crew chiefs reported seeing bright and long exhaust flames coming from a right-hand side engine along with loud and sharp backfiring noises. One witness described a propellor running at high rpm, a condition caused by low oil pressure or loss of power.

In 2001 the engineering crew chief Teddy Hanks wrote, ‘The fact that B-17C (VH-CBA) performed satisfactorily the day before the crash cannot absolve its 4 engines of blame.’ Cutler notes how wartime aircraft engines were kept serviceable by cannibalisation or scavenging of parts. Two Australian-sourced remanufactured engines had failed on their test flight, with a magnetic chip trap producing a harvest of metal from each. Replacements came slowly by ship from the US. It is not known what if any action was taken to protect the remaining engines during the aircraft’s lay-up. A minor note is that as an early production B-17, the C-model lacked the remotely controlled cowl flaps that were used to control engine temperature during ground running and take-off on later models. These were an important part of engine management on later versions of the B-17.

Loading

As a bomber, the B-17 was designed to carry its load near its centres of gravity and lift. The importance of balanced loading was known to the 46th Troop Carrier Squadron and, therefore, the passengers were located primarily in the bomb bay area, with some seated on the floor of the radio operator’s compartment. The sole survivor, Corporal Foye Kenneth Roberts, sat there.

Captain Cutler kept a manifest of the flight, which his son found in 1999. It showed a taxi weight of 21,233 kg, close to but under the B-17C’s maximum take-off weight of 21,545 kg. Not accounted for in the manifest were several cases of bully beef found amid the wreckage. Years later, Roberts described how passengers were carrying ‘goodies’ for their flight home. It seems unlikely that such contraband could have weighed more than the 312 kg margin between manifest and MTOW but it put the aircraft closer to its limit and may have shifted the centre of gravity.

Crew performance

Without knowing exactly what circumstances faced the crew, it is impossible to judge whether their response was adequate. In other words: just because the aircraft crashed does not necessarily mean the crew’s performance was deficient. Why the aircraft was turned left at 250–300 feet cannot be known. It is notable that in the case of a right-engine power loss or fire, as reported by witnesses, turning left at an appropriate height would have been the correct response for a return to the airfield.

The aircraft had been delayed by 30 minutes but took off into morning ground fog estimated at 200–250 feet deep. This would have added to the crew’s workload, requiring instrument reference in the first seconds of the flight. At that stage in the war, before the massive pilot training efforts of the US and the Empire Air Training Scheme achieved full capacity, many pilots went to war with little more than cursory training in instrument flight. The B-17’s pilot, First Lieutenant Gidcumb, is reported to have about 300 hours total time, about the same as the copilot, Flight Officer William C Erb.

So it was that a well-used aircraft that had developed a reputation for unreliability remained in use.

In the words of crew chief Teddy Hanks, ‘I don’t believe the maintenance crew should feel any guilt for the aircraft’s fateful crash. I do believe, however, that those prone to accept the pilot error theory as cause of the tragedy are doing a grievous and unfounded injustice to the pilot and copilot.’

The elements combined to create a horrible predicament for a relatively inexperienced crew: after taking off in compromised visibility, at close to maximum weight, most likely with an aerodynamically degraded airframe, they are faced by either fire or power loss. For unknown reasons, they begin a series of turns to return to the airfield. Just as their descent reaches its most critical stage, they are back in the fog bank and relying on instruments with the ground very close. The one element which could have been altered in this situation was timing: if departing half an hour later, the ground fog would have at least begun to lift.

Event horizon

Bakers Creek remains the most deadly aircraft crash on Australian soil but was only a drop in the ocean of suffering represented by the Second World War. Author Max Hastings quotes a death toll of 60 million, which averages to 27,000 people for every day of the conflict. This in no way denies the trauma of the dead, the bereaved, the survivor and the observers.

Many things have changed in aviation but overloading, imbalance, power loss, weather and inexperience can all still kill.

Although they did not die in battle, the victims of Bakers Creek were undoubtedly victims of war. The crash that killed them was a consequence of the desperation and improvisation of war – the B-17’s Australian civil registration is an emblem of this needs-must, make-do-and-mend approach. So it was that a well-used aircraft that had developed a reputation for unreliability remained in use. Despite being less than 3 years old, it had several of the hallmarks of an ageing aircraft. The many layers of James Reason’s Swiss cheese model – active failures, preconditions, triggering events and defences, or their lack – can also be clearly seen in retrospect.

Tragedies from long ago inevitably disappear over the horizon of living memory. It’s a metaphorical sink rate every bit as implacable as the B-17’s descent on that fatal morning. Although the noble efforts of Col Benson, Robert Cutler, the city government of Mackay and many others have delayed and even reversed this, the story, even when remembered, inevitably evolves from the concrete to the abstract. But for pilots, despatchers, engineers and aircraft loaders, the lessons of Bakers Creek are as real and relevant as ever. Many things have changed in aviation but overloading, imbalance, power loss, weather and inexperience can all still kill.

Comments are closed.