Knowing how your aircraft is trending is a refined form of situational awareness that should always be in fashion.

Pilots tend to be pretty good at noting the aeroplane’s state, that is, whether it is high or low on altitude or glidepath, or left or right of heading or ground track, either en route and for instrument and visual approaches.

Flight instructors are pretty good at teaching awareness of the aeroplane’s state and point out the state frequently during training: ‘You’re left of course’, ‘Check your altitude.’ However, in my experience as an instructor, most pilots are less aware of evaluating and using knowledge of the aircraft’s trend; many flight instructors are not so great at teaching trend management, if they overtly teach it at all.

Evaluating both state and trend is vital to precision and safety, not only so you can brag about being within 20 feet of a desired altitude or other tight tolerance, but also so you can land smoothly and consistently in the planned runway touchdown zone, avoid landing short or long, or any number of other times when precision means safety.

You need to be able to spot not only whether you are high on the approach, for example, or precisely on course and glidepath, but also whether your current trend is to keep the needles centred or the PAPI red over white. If you’re not, you need to adjust your trend to make a smooth correction without overcontrolling. Learning to detect and use both state and trend for all aspects of your flying is vital to being a smoother, safer and more precise pilot.

Learning to detect and use both state and trend for all aspects of your flying is vital to being a smoother, safer and more precise pilot.

An example

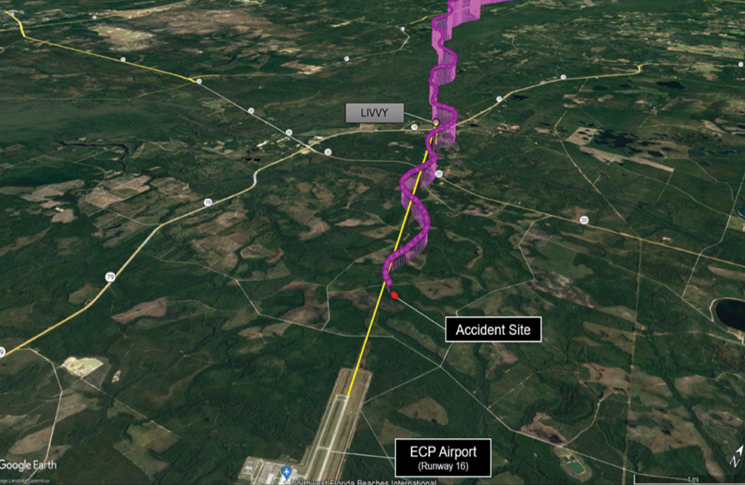

A US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) report on the crash of a Cessna 182 is an extreme example of noting state but not managing trend. Two people died when the pilot lost control while flying the ILS 16 approach into Panama City, Florida, on 6 March 2022. The automatic terminal information service (ATIS) reported ceiling 200 overcast, visibility 2 miles, with light winds (6 knots) almost straight down the runway (wind blowing from 150˚).

The NTSB preliminary report, which is unusually detailed for a ‘prelim’, states:

Review of the ADS-B flight track in the final approach phase found that the aeroplane’s course deviated left and right from the initial approach fix to the accident site, which was 1.55 nautical miles from the runway threshold. The aeroplane’s altitude showed momentary descents and climbs while on final approach. The final ADS-B data point recorded the aeroplane at 75 feet mean sea level, 144 knots ground speed, with a ground track heading of 130°. Figure 1 shows the accident site, the final approach course represented as the yellow line, and the aeroplane’s flight track represented in the magenta line.

The tower air traffic controller advised the pilot of his deviations from the final approach course several times after the pilot was inside the final approach fix, as well as radioing one ‘low altitude alert’ when the aeroplane had descended well below glideslope. The pilot appears to have continued to manoeuvre, left and right, up and down, perhaps in response to these calls but without the precision necessary to return to course and glideslope.

To better manage the aeroplane’s current state and trend, constantly ask yourself 3 questions:

- Where am I?

- Where am I going?

- How quickly am I going there?

Where am I?

The part that almost all pilots seem to get right is evaluating whether the aeroplane is on course and on altitude or glidepath. ‘I’m on altitude’, ‘I’m high’ or ‘I’m low’ is easy enough to detect – look at the altimeter or, if on an approach, the visual or electronic glidepath or glideslope.

‘I’m on heading’ and ‘I’m on course’, or ‘I’m left of course’ or ‘right of course’ are quick judgements made by looking at the directional gyro, heading indicator or horizontal situation indicator (HSI), the GPS ‘magenta line’ or display of a ground-based navigational aid.

The combination of vertical (altitude/glidepath) and horizontal (heading/course) is the aeroplane’s current state. However, as I said, the state – where you currently are – is only the beginning of flying precisely.

Where am I going?

It’s equally important to know the aeroplane’s trend. I know where I am right now – but where am I going?

Way back when I did a lot of private and instrument training, I’d show this to my students with a quick exercise. I taught in a rural area in the central United States. Cowra and Narromine in NSW have similar terrain and flying environment. The closest VORs were about 70 kilometers away – close enough for solid reception, but far enough away that a VOR radial is fairly wide.

I’d have my student tune in one of the closest VORs and, once they identified the station and centred the needle, I’d have them fly a level, steep turn. If you are sufficiently distant from a VOR, you can fly a complete 360˚ turn and the course deviation indicator (CDI) needle remains centred, or very nearly so.

My point: having the navigation course or localiser centred (even using today’s GPS) tells you where you are at the moment – your state relative to the desired course – but it does not tell you where you are going – whether your trend is to keep the needle centred or if you’re just flying through the course line while headed in another direction.

In other words, having the needle centred does not necessarily mean you are heading in the right direction. You could be 90 or even 180 degrees off course and just at that one moment have the needle centred.

The same is true with altitude or glideslope or glidepath. The altimeter may read precisely on altitude or the glideslope be perfectly centred but, if the vertical speed is not correct, it won’t stay there long. The glidepath needle may be centred, but if your rate of descent is too little or too great, you’re just flying through it, not following it down.

In other words, having the needle centred does not necessarily mean you are heading in the right direction.

Knowing and evaluating the aeroplane’s state is the first element of precision flight. Detecting the trend – whether you’ll remain on heading/course and altitude/glidepath – is the second. But if you jerk the controls left or right, up or down, to react to the aeroplane’s state and trend, you’ll describe a flight path like that of the unfortunate Cessna 182. How do you use the information you see outside or on the instrument panel to manage trend for precision flight?

How quickly am I going there?

The third element of precision flight is to use aircraft pitch attitude and heading to keep the needles centred or the altimeter spot on, or to establish a small correction if needed that creates a trend in the right direction but at a controlled rate to avoid overcorrecting. It’s no coincidence that most heading bugs are sized so their edges are about 5 degrees left and right of the heading at its centre (Figure 2).

If you are left of course, correct by turning to the heading that is under the right edge of the heading bug. Then hold that heading to establish a manageable trend to centre the needle. Do not change the heading bug – you’ll return to the indicated heading once the needle centres and you’re back on course.

If you’re right of course, turn to the heading under the left edge of the bug to establish your trend. As winds change, you may move the heading bug to what you estimate is a good wind correction but, after that, still use the left and right edges of the bug for manageable corrections that prevent overshooting.

Most instrument panels don’t have a vertical speed bug but remember this: at 90-knot ground speed, the standard 3˚ glidepath requires a 500-fpm rate of descent. At 120-knots ground speed, it requires 600 fpm. If your glidepath needle is centred on an approach, maintain 500 to 600 fpm to keep it centred. If you’re high on glidepath, adjust pitch or power to increase vertical speed by 200 or 300 fpm to reacquire the glideslope.

Once the glideslope centres, return to the attitude and power setting that causes a 500 to 600 fpm rate of descent. If you’re low, add power and adjust pitch for a reduced rate of descent, up to but not beyond level flight. Fly this shallower descent until the needle centres, then return to the pitch and power needed for 500 to 600 fpm.

Some commonly installed upgrade panel displays provide additional trend cues. For example, the Garmin G500 TXi in the A36 Bonanza I usually fly has several.

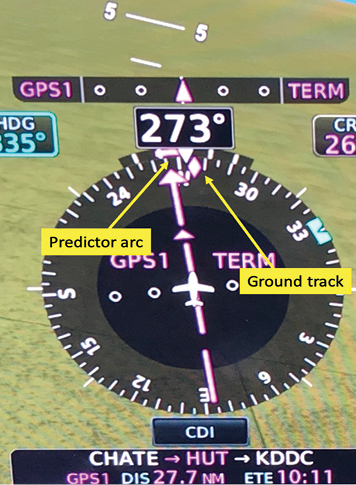

The terminology and specifics vary by make and model, but most recent primary flight displays (PFDs) provide trend information. When the aeroplane is turning, the end of an arc on the heading indicator predicts what the heading will be at some time in the future (6 seconds on the TXi). A diamond or other indicator depicts the aeroplane’s current ground track, adjusted for winds.

Some displays have a flight path marker (FPM) – a ‘pipper’ or ‘gunsight’ – that shows where the aeroplane is going based on its ground track and vertical speed (Figure 4). On final approach you can simply keep the FPM on your desired runway touchdown point to aim directly to that spot even in strong crosswinds. Keep the FPM on the white level horizon line and the aeroplane stays precisely on altitude, even in steep turns.

Correcting

Airline pilots have long known the critical importance of constantly monitoring pitch, vertical speed, airspeed and power, not just on approach but, for example, managing an engine failure on take-off. Eventually it becomes almost second nature for that monitoring to become a real time predictor of ‘what’s happening next’.

Watch a video of a 2-pilot crew flying an instrument approach and you’ll often hear the pilot monitoring (the crew member not actually flying the aeroplane) call out the aeroplane’s state, for example, ‘On course, one dot low’. (Some operations specifications would have the pilot monitoring say, ‘On course, correct up’ to avoid confusion about what the pilot flying needs to do.) The pilot flying would establish a controlled trend in the proper direction and repeat aloud, ‘Correcting up’ or similar.

Although in the single-pilot world we’re almost always both the pilot flying and pilot monitoring, I do it out loud as well: ‘Left of course, correcting right’ or ‘One dot high, correcting down.’ Try it and see if it helps you become more controlled and precise.

Whether you have the latest in electronic aids for trend analysis or are flying with a classic panel or whether you’re flying a long, visual final or an instrument approach to minimums, then constantly evaluating where you are, where you’re going and how quickly you’ll get there allows you to manage both the aeroplane’s state and trend, and command where it is going with precision.