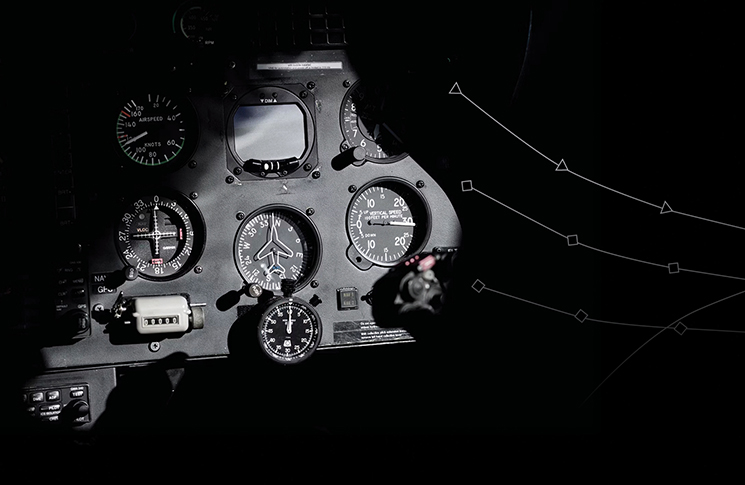

The good old bad old days

The operational history of Frank Robinson’s helicopter designs in Australia is a case study in how safety comes from the interaction of engineering, training and culture.

By Rob Rich

Frank Robinson, founder of the helicopter company that bears his name, died on 12 November last year. He was one of a handful of people in aviation history to have redefined an entire category of aircraft.

Robinson, a former employee of Bell Helicopter and Hughes Helicopters, branched out on his own in 1973, with the goal of designing and manufacturing a light, inexpensive and safe helicopter for the general aviation market. This he achieved, with Robinson Helicopter Company producing more than 13,500 aircraft and becoming by far the world’s largest helicopter manufacturer.

In March 1979, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) issued the Type Certificate for R22, a lightweight 2‑seat helicopter that had first appeared as a sketch on Frank Robinson’s kitchen table 6 years earlier. In October 1979, the first production R22 was delivered to a customer.

Robinson’s concept of a new light helicopter captured the imagination of the US aviation community. When delivering the first R22, he surprised the helicopter community when he announced he had a backlog of 587 orders for the type.

However, in January 1981, just after the 100th R22 was delivered, the FAA began investigating a series of unexplained fatal accidents in R22s. Some pilots were not familiar with the handling differences between the R22’s low-inertia main rotor system and the high-inertia main rotor equipped helicopters that entered the global market 3 decades earlier after World War II.

Robinson’s concept of a new light helicopter captured the imagination of the US aviation community.

Fortunately, the FAA reported nothing wrong with the R22’s design; although it was easy to get into a main rotor stall situation if the main rotor RPM and airspeed were allowed to fall below limits listed in the R22 Pilot’s Operating Handbook. The FAA asked Robinson to provide a solution for what was really a human factors handling problem and not a design technical issue.

In October 1982, the original R22 Robinson factory pilot safety course was launched. Designed for flight instructors, the syllabus was aimed at standardising training for the R22 at flight schools where R22s were then being widely used. Although it took almost 2 years to implement the course, it was an outstanding success. Frank often proudly stated the upgrading of instructor skills had resulted in a lowering of the accident rate of course graduates by 60 per cent.

Robinson R22s began to appear in Australia in the early 1980s when the civilian helicopter fleet numbered around 400. Sales were initially slow as the Australian helicopter operators were sceptical about the R22’s durability. They questioned its suitability for rural tasks such as agricultural spraying and sling operations for the building of telephone repeater towers.

Further, during the next decade, the success of the safety course was not understood by Australia’s aviation safety agencies of the early 1990s. Thus, the lessons from Robinson’s bad old days were not readily available to Australian flying schools. It was of little help to the new mustering companies being established in Australia’s northern regions.

Selling safety in Australia

During Frank’s regular visits to Australia in the early 1990s, he was often a guest speaker at air shows. He described why he started the pilot safety course to avoid FAA cancelling certification for the R22. He often said he was concerned about the high accident rate in Australia. He said 10 per cent of his sales were in Australia, but the accident rate here was twice the loss rate in the US. In particular, the maintenance of his machines in Australia and New Zealand caused him to shake his head in disbelief.

Frank cited issues including false logbooks, unauthorised (bogus) parts, use of non-approved fuels and over stressing of airframes and rotor blades from violent manoeuvring during low-level mustering or feral animal culling. Then the global insurance industry declared war on the ‘Down Under cowboys’ who were not complying with Robinson’s mandatory servicing and overhaul requirements, by declaring insurance policies for Robinson helicopters in Australia would not be renewed.

In late 1992, the forerunner of QBE Aviation Insurance realised the threatened global insurance action would make the Robinson products uninsurable. This would severely damage the Australian helicopter industry as by now more than half the Australian helicopter fleet were Robinsons.

The Bureau of Infrastructure and Transport Research Economics (BITRE) found more than half the Robinsons were used for mustering. They advised that the mustering group – about 25 per cent of the national fleet – flew more hours than the rest of the industry combined.

But the worse was to come when the Bureau of Air Safety Investigation (now the Australian Transport Safety Bureau) said mustering operators had an accident (and fatal) rate twice that of commercial helicopter charter operators.

Commercial pilots were quick to blame their high insurance costs on the losses incurred by private owner-pilots. They said government data showed:

- mustering and crop-spraying pilots – operating at low levels – had an accident rate twice that of charter pilots

- private pilots had a rate twice that of the mustering and crop-spraying pilots, or 4 times higher than helicopter charter pilots.

Insurer takes a stand

In 1993, aviation insurers and the Helicopter Association of Australia (HAA) agreed to evaluate the R22 Robinson factory pilot safety course, aiming to lower the Australian accident rate to that in the US, that is, a 60 per cent reduction in accidents for safety course graduates.

BITRE was able to report the accident rate was reduced by 68 per cent, an outcome similar to the US experience.

When I was chief executive of Brisbane-based Aviation Safety Pty Ltd, I attended Frank’s course in the US and strongly recommended a version of the course be established in Australia. Frank and his chief instructor Tim Tucker sent training and operational manuals to Australia and this information was shared with other safety course providers such as Queensland TAFE, which began an innovative program. The TAFE course also catered for maintenance engineers who were often overlooked by educational institutions.

A school for safety

Subsequently, Aviation Safety Pty Ltd ran a Robinson pilot safety course from 1993 for 25 years, at 105 locations in Australia and New Zealand. An estimated 3,000 attendees were issued certificates to obtain insurance discounts or be eligible to be employed as a Robinson pilot. As a result, BITRE was able to report the accident rate was reduced by 68 per cent, an outcome similar to the US experience.

In recent times, very few courses have been conducted in Australia, although New Zealand has legislated a safety course as a mandatory requirement for pilots before flying R22 or R44 helicopters.

Last year, there were 2 fatal R22 and one R44 accidents, killing a total of 4 people, and several other crashes in which Robinson helicopters were destroyed and people injured. Although the rate of fatal accidents in Robinson helicopters has improved to stabilise at a lower level, every crash, whether fatal or not, should remind us that the struggle for safety never ends. Like all aircraft, the Robinson helicopter’s enemies are gravity, mechanical failure and ignorance.

|

Rob Rich is a former military and civilian aeroplane and helicopter instructor. He was the senior maintenance test pilot at Hawker de Havilland, Sydney, during a break in military service and is now a publisher of newsletters about drones and helicopters. |

thanks for the information and amazing picture