By Alan Bradshaw

The darkness of regional Australia at night proves to be more than a match for a city slicker’s night VFR rating.

My lifelong dream to fly was realised in August 2010 when, at the age of 61, I passed the practical test for a private pilot licence. It was official – now I could really go flying!

After a year or so hiring a Piper Warrior at Bendigo, the dream of securing an aircraft of one’s own intensified. There would be no standing in line for a hire aircraft, no deadlines to meet returning the hired machine and getting to know inside-out the personality of your own aircraft would make one a safer flyer; so, the justifications developed for a SKI (spend the kids’ inheritance) trip. When a low hours Piper Saratoga came on the market in the US thanks to the global financial crisis, the opportunity was too good to resist.

Having purchased an aircraft, endorsements for manual propeller pitch control and retractable undercarriage were straightforward. The next issue that seemed worthwhile addressing was the deadline imposed on VFR pilots by last light. So began training for a night VFR rating. Flying VFR at night with an instructor was a lot of fun.

I lost altitude in the turn, which had progressed beyond rate one to the commencement of a rollover!

Practising touch and goes in a crosswind at night could quickly become a competition between student and instructor over who could pull off the best approach and smoothest landing. Taking the practical test continued the learning process – a wind change can really upset your dead-reckoning and sometimes the pilot activated lighting system at an airport can fail to respond, several times in a row!

With a night VFR rating in the bag, flying in the evening light became a serene time to fly home over the city lights. Maintaining the recency of a night VFR rating is not arduous. One take-off and landing every 6 months or, with passengers on board, 3 within the last 90 days to be current. Not a big ask. But therein may lurk a problem.

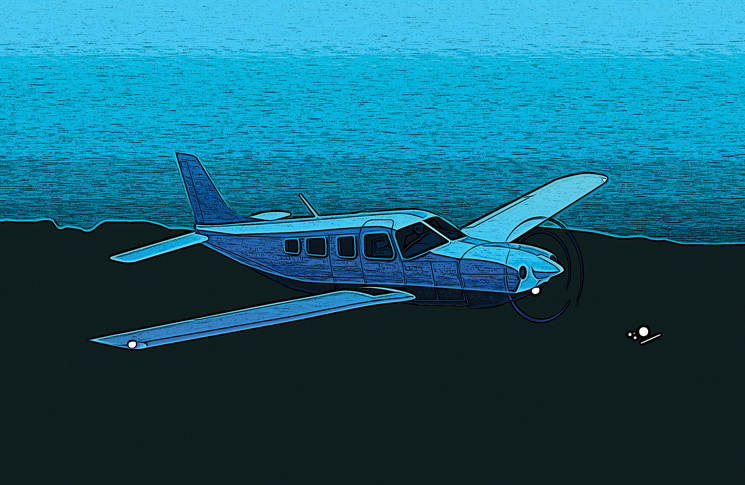

It was a moonless night in March 2015 when I took off from Bendigo on a solo night navigation exercise. I had filed Deniliquin-Echuca-Bendigo which would accomplish 3 take-offs and landings. I had flown to Deniliquin many times but never at night. As I approached Deniliquin, there were 3 aircraft in the circuit practicing night circuits. I slotted into the circuit and performed a smooth landing before powering up and rounding out to commence my climb, focusing on the attitude indicator until 500 feet. At 500 feet I had been taught to look out for the horizon and, if it was not visible, go back to the attitude indicator and commence a climbing turn. I looked out and could see a solitary light through the windscreen as I commenced a left turn.

Deniliquin Airport is south of the town so taking off to the south-west on RWY 24 on a moonless night is taking off into a wall of darkness, except for that one light! I watched as it rose up and to the right of my windscreen before checking my instruments. To my horror the altimeter was going backwards as I lost altitude in the turn, which had progressed beyond rate one to the commencement of a rollover!

I quickly corrected my attitude and resumed a gentle climb out to the south as I pondered what might have been.

My night flying up until this flight had been confined to airports that I was very familiar with by day. On this occasion I had chosen a more remote airport that was relatively unfamiliar by day and totally unfamiliar by night – and had gone there on a moonless night! I had not yet commenced training for an instrument rating, so my scan frequency had not been up-scaled to flying on instruments in IMC.

I became fixated on that one light as I sought a visual horizon and fortunately, I broke out of that fixation in time! Close call? It was at least close to becoming a close call!

Lessons learnt:

My takeaway from this incident was to stay on instruments until 1,000 feet above the airport before looking for the horizon. How far I descended I do not recall as I was focused on achieving a positive rate of climb. Having a 1,000-foot buffer compared to 500 feet has an appeal.

My resolution has evolved to not flying at night at all, even after gaining a PIFR rating. Why? I fly in daylight almost 100% of the time where I practise my skills under VFR and IFR.

It is my belief that if one is not motivated to devote a good portion of one’s flying hours to night flying, arguably in the order of 25%, then one should not risk the occasional night flight. One night take-off and landing every 6 months for recency falls well short of my personal minimum.

- Don’t forget to check out the audio close calls. Visit flightsafetyaustralia.com/audio and hear the stories come to life.

Have you had a close call?

8 in 10 pilots say they learn best from other pilots and your narrow escape can be a valuable lesson.

We invite you to share your experience to help us improve aviation safety, whatever your role.

Find out more and share your close call here.

Comments are closed.