The difference between a safe journey and a dangerous debacle is in the preparation, so make good use of your kitchen table.

Before any flight planning exercise, we need to stop and think.

Every flight has a different focus, urgency, personality. Yes, there are essential steps to follow in compiling a flight plan, but it might make you try harder if you know why you’re even doing one.

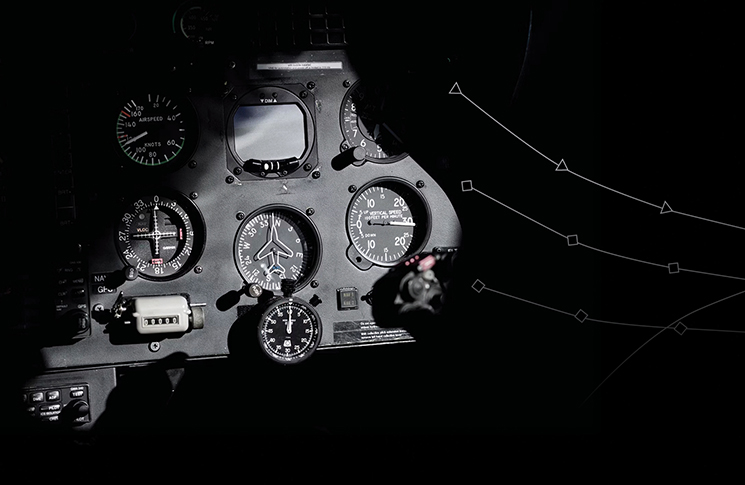

The way I look at it, any way that I can alleviate the workload in my cockpit, I’m all for it. With weather, traffic, comms, navigation and photography duties, flying offers up quite enough for us to concentrate on while we’re in the air – who needs more jobs to do?

If you spend some time on the ground gathering all the information about your flight you could possible need, and adding this to your flight plan in plain view on your lap, that’s just freed up a whole lot of headspace.

It doesn’t matter whether you’re planning the bucket list flying safari over 3,000 nm, or an A-to-B jaunt to visit your Mum, every flight needs a flight plan. If you’re daunted by the prospect of a three-week safari, don’t be – it’s just a series of daily nav exercises. Let’s look at flight planning for a leg.

Gather your charts, fold them so your track and surrounds are visible, put them in order and slot them into your flight plan folder.

VFR flight planning – the process

Restricted airspace

Let’s take a slight diversion here and talk about when flight planning can get a little interesting. Let’s say you’re on the long-anticipated fishing trip with your best mates in the Top End. You’ve left the rain and icy winds of Victoria behind; you’re down to a t-shirt and shorts and you can nearly smell the fried barra as you cross into the NT heading north.

War games

Nothing puts a sharper little edge to the cruisey mood of flying the outback than when your day includes calling in on our defence force.

Your little fleet of 2 aircraft is now on its way across the NT to Katherine Gorge. You’ve just spent a hilarious night at Daly Waters and now want to call in to the famous Katherine Gorge to try out their sunset gorge cruise before continuing north.

On the WAC, the town of Katherine looks like a sleepy little outpost in the middle of nowhere. However, replace the WAC with a VNC or an ERC and the scene livens up considerably.

Nothing puts a sharper little edge to the cruisey mood of flying the outback than when your day includes calling in on our defence force.

All those red barbed lines and labelled slabs of airspace mean you’ve found the home of The Royal Australian Air Force base at Tindal, 8 nm outside Katherine and 154 nm south-east of Darwin. As you’ll see from the charts (the Darwin/Tindal VNC is excellent), its numerous associated restricted areas cover a vast expanse across the region, which you’re going to find hard to avoid if you’re heading for popular safari destinations like Darwin, Kununurra or Kakadu. In fact Tindal

is Australia’s largest area of controlled airspace and home to some of Australia’s most significant defence installations.

Understandably, the RAAF like to know who’s around and what you’re up to, so you’re definitely going to have to knock before you enter. Plan to make your initial inbound call at about 50 nm. ATC loves lots of notice. And just so you know what they’re up to, you’ll find a riot of NOTAMs in place on any given day of the calendar, laying out where and when the military jets are flying. In NAIPS/Location briefing, bring up YPTN (Tindal Aerodrome). In NAIPS/restricted area briefing, bring up TNX (Tindal Airspace) in airspace groups. You can also bring up Area 80 in the restricted area briefing. It’s a good idea to check the Brisbane FIR NOTAMs too. Make sure you lodge a flight plan and scrutinise those NOTAMs like your life depends on it.

Anyway, since you’re taking us on a fabulous sunset cruise on Katherine Gorge this evening, you need to not only scoot through a fair bit of their airspace, but you need to land your 2 aircraft on that huge runway at Tindal, then find the civilian Avgas bowser. Preparation for today’s flying starts well before today.

We’re here to help

While in the early planning stages of any flight into restricted airspace, give yourself a heads up on procedures before you leave home by reading the location’s entry in ERSA. If there is any part of the procedures for arrival or departure that you don’t understand, do not hesitate to pick up the phone and ask! In the ERSA Tindal entry for example, there is a phone number printed there for any ATC inquiries. Use it. It wouldn’t be in there unless the controllers were happy to help us out.

I’ve rung military towers all over Australia and have been met with nothing except courteous, helpful advice and a noticeable dose of thanks that I made the effort to ring and clarify procedures. This goes for civilian-controlled airspace as well.

When we were developing the original OnTrack program for CASA, we interviewed tower managers all around Australia and their most common plea was just this. ‘If pilots don’t understand our procedures, they are more than welcome to call and ask us. We’d far prefer helping them out before their flight, give them a heads-up on what they can potentially expect when they get here. It’s far safer than us assuming they know what they are doing, then trying to untangle their mistakes in the air. We’re all on the same page here –

we only come to work to keep everyone safe.’

That’s nice to know, isn’t it? This is all part of thorough flight planning. There is a hell of a lot that goes into any and every flight. Yes, you may have flown this route a hundred times, but that doesn’t negate the need to have all necessary information at your fingertips or written down clearly on your plan.

If pilots don’t understand our procedures, they are more than welcome to call and ask us.

Using current issues of ERSA and charts is a no-brainer. Frequencies change! Many itinerant pilots visiting Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre took years and years to cotton on to the change of CTAF frequency out there, from 126.7 to 127.8, that was introduced when scenic traffic ramped up. Monitoring and transmitting on the wrong frequency is one of the most dangerous mistakes we can make.

Going somewhere special?

Maybe you’re heading across Bass Strait to go to Hobart’s MONA? Flight planning for that one needs some extra reading. There’s a section in the back of the ERSA called GEN-SP (Special procedures not associated with an aerodrome). The Bass Strait crossing is listed first, at SP1. How do you know it exists? On the ERC L1, halfway across the strait, you’ll see SP1 in a small purple box (red on a VTC). After you’ve digested that, flick through the following pages and note which other regions or locations have been allocated a Special Procedures entry. They include the Bungle Bungles, Uluru, Great Barrier Reef, Kati Thanda‑Lake Eyre and various areas where biosecurity requirements exist.

Following on from the Special Procedures, you’ll find the FN (fly neighbourly) advice. There are currently 24 of these areas around Australia and you’ll find their location on the ERCL marked with an FN identifier in an identical small purple box (red on a VTC). If your track takes you anywhere near these areas, a careful read of the procedures is an important part of your flight planning.

Most pilots are familiar with a WAC and a VTC, but it’s a good idea to take a moment to get to know the value of the PCA and the ERC in particular. Sometimes the information is hard to find in the clutter of the chart, but if it’s there, you will be far better prepared for your flight after having read the related information.

If you give it the time it deserves, thorough flight planning delivers a far more relaxed, safe and legal flight than if you just whack your track on an EFB and follow the magenta line. That’s a sure recipe for surprises you really don’t need.

EFBs certainly have their place in early flight planning. They are a brilliant tool for working out a multi‑leg itinerary with waypoint options over large expanses of the country. After years of laying out acres of WACs across the loungeroom floor, there’s great joy in dragging that magenta line around the screen mercilessly and instantly being offered mileage and, thus, time intervals for each leg. Fuel stop selections and overnight stops are way easier to calculate – just make sure you get those charts out for the final planning.

| See CASA’s Flight planning kit that helps low‑hour VFR pilots develop good planning habits. Visit the Pilot safety hub for flight planning resources casa.gov.au/pilots |

Great article Shelley, thanks.

I created an MS Word Template for flight planning. It has a checklist that covers the procedure outlined in your article. I also print off the digital ERSA pages for airports from the CASA website (always up to date!) and draw the circuit directions, and annotate with circuit heights and overfly heights. I do the same for alternate airports where required.

I also call the BOM, who are happy to discuss the current weather conditions and provide advice. I also ring the destination airport, not only for PPR, but also to establish local weather and any local issues. I recall on one occasion I saved myself a lot of grief when the local contact told me that (unexpected) fog covered the airport.

By ensuring I’ve covered all the basic stuff in my flight planning, it leaves me free to deal with the unexpected stuff.