Behind an error that killed 9 people, investigators found an insidious and potent psychological force.

Sikorsky S-76B, N72EX

Calabasas, California

0946, 26 January 2020

In their separate ways, both the pilot and the passenger were inspirational American success stories.

The pilot had moved to the United States in his teens from Lebanon and saved money for flying lessons while working as a car park attendant. He got his helicopter licence in 2001 and worked initially as an instructor, generating a record of safety and competency that opened the door to a job at a helicopter charter company in Los Angeles.

There he met a famous passenger, a sportsman fluent in Italian after living there as a teenager. This person had the distinction of having been drafted into professional basketball straight out of high school competition. Over his 20-year basketball career, he scored 33,643 points, all with the Los Angeles Lakers, earning legendary status in his adopted city.

A rapport developed between the two and the passenger often specifically asked to be flown by the pilot, whose name was Ara Zobayan. The passenger was Kobe Bryant. It’s important to remember that the crash that killed them both, on 26 January 2020, also ended the lives of 7 other people, including Bryant’s 13‑year‑old daughter. But the underlying factor behind the crash was the personal dynamic between Bryant and Zobayan.

That Sunday morning’s flight was to have been from John Wayne Orange County Airport, in the south of the Los Angeles conurbation, to Camarillo, about 140 km north. Zobayan completed a company flight risk analysis form about 2 hours before take-off. Based on the conditions then, it yielded a score of 12. A score of more than 45 would have required him to consult the director of operations.

By 9 am conditions had deteriorated and, had Zobayan filled in the form then, he would have had to specify an alternative flight plan and seek input from the director of operations. But the company’s guidance on precisely when a flight risk analysis should be done was vague and the Sikorsky S-76B departed at 09:08 am. It rose into calm air with visibility of 4 km, haze and a broken cloud ceiling of 1,100 ft AGL. The Orange County controller called the aircraft to report similar conditions at Van Nuys Airport, which was near the turning point of the aircraft’s dogleg route.

A security camera on the freeway showed the helicopter shortly before its destruction as a ghostly half-hidden presence, about 400 feet above ground level and moving quickly through the overcast.

There was an 11-minute hold before passing through Burbank Airport’s airspace to allow several IFR flights to approach and land. By now, Zobayan had requested and been granted special VFR and was flying below usual VFR minimums. IFR departures from Burbank meant Zobayan’s original plan to track west through the San Fernando Valley following the Ronald Reagan Freeway was unavailable. Instead, he would skirt north of Van Nuys’s airspace, then turn south and follow US 101, the Ventura Freeway, west towards Camarillo.

Zobayan asked the controllers at San Diego-based SoCal Approach for Flight Following on this sector. Concerned about the ability to track a low-flying aircraft, the SoCal controller asked the pilot if he planned to ‘stay down low … all the way to [Camarillo].’ Zobayan replied, ‘Yes sir, low altitude’.

Into IMC

The Ventura Freeway is a celebrated but fundamentally mundane traffic artery that contains an unsung seasonal aviation hazard – on the rare occasions when southern California is subject to fog and low cloud, these conditions persist much longer where the freeway climbs into the hills near Calabasas. The report by the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) into the subsequent crash of the Sikorsky says, ‘A private pilot who resided near and frequently drove along US 101 near the accident site said the topography in the area tended to channel fog up from the coast (from the west) that would stack up against the hills in that area.’

A security camera on the freeway showed the helicopter shortly before its destruction as a ghostly half-hidden presence, about 400 feet above ground level and moving quickly through the overcast. Nearby cameras covering baseball fields incidentally showed the tops of the Calabasas hills completely obscured.

Zobayan held a commercial pilot certificate with rotorcraft-helicopter and instrument ratings but of his 8,577 hours, only about 75 were IFR, and at least 68.2 of those hours had been in a simulator. However, he had completed training in inadvertent entry into instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) and unusual attitude recovery the previous May.

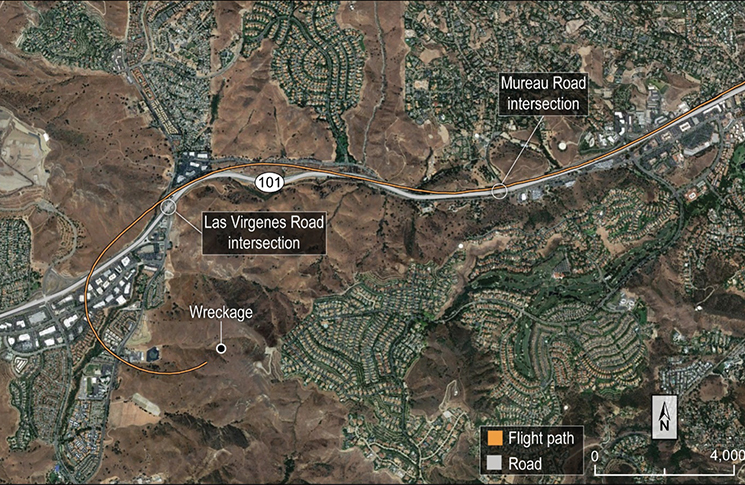

At 09.44.34 the helicopter entered the low cloud over Calabasas. Zobayan’s response was to climb through the cloud into clear air, and he told SoCal Approach of his action. The controller assumed the flight was climbing through a hole in the clouds.

Zobayan’s IMC practice 7 months earlier had included performing a climb out using the autopilot (the preferred method), and by hand flying. For reasons unknown, he now hand-flew his upwards exit.

ADS-B data shows about 36 seconds into the climb, the helicopter went into a left turn that quickly became steep and put the helicopter into a descent. Seven seconds later, Zaboyan responded to a SoCal Approach request to ‘Say intentions’ by saying he was climbing to 4,000 feet. ADS-B data shows the helicopter in a rapid descent as he spoke this.

An experienced pilot had killed himself, his friend and 7 other people by making an elementary mistake. But why?

Had the helicopter continued to climb as its pilot presumably believed it was doing, it would have broken the cloud tops after maybe another 15 seconds. Instead, 2 mountain bikers in the grassy hills below saw an appalling sight.

From the NTSB report, ‘He heard what he described as the normal sound of a helicopter flying for about 20 seconds, then he suddenly saw the descending helicopter emerge from the clouds and roll to the left. He estimated that he saw the helicopter for about 1 to 2 seconds before it struck the terrain and erupted into flames about 200 ft (55 m) from his location.’

The riders swooped downhill to the wreckage but saw nothing could be done for anyone on board. The impact made a crater 7.5 m long, 4.5 m across and 60 cm deep.

Analysis

An experienced pilot had killed himself, his friend and 7 other people by making an elementary mistake. But why?

The immediate cause was a vestibular somatogyral or ‘false sensation’ illusion. The pilot had probably suffered from ‘the leans’ during the helicopter’s final left turn. This would have led him to incorrectly perceive that the helicopter was flying straight and level despite it being in a banked left turn. It is a compelling and distressing illusion, even for experienced instrument pilots. ‘In addition, the pilot’s initiation of communication with the controller introduced a task load that continued for the remainder of the flight,’ the NTSB said.

Regarding broader causes, the NTSB quickly ruled out pilot impairment or intoxication, aircraft faults or pressure to complete the flight from the charter company or its celebrated client. Island Express, the helicopter operator, had not been afraid to cancel 150 flights because of weather in 2019 and, in 2020, had already cancelled 13 flights. No significant procedural deviations had occurred in the helicopter’s dealings with ATC.

So where had the pilot’s decision to press on, at 140 knots, despite his training recommending slowing to 80 knots or less when approaching IMC, come from? The NTSB concluded it came from within himself.

Kobe Bryant was in the top rank of American fame and power, as evidenced by tributes paid to him at the Grammy Awards (on the day of the crash) and weeks later at the Oscars. The prestige of being his trusted servant and friend appears to have been subtly corrosive to safety. As the NTSB described it, ‘A number of factors were present that may have influenced the pilot to place pressure on himself (self-induced pressure) to complete the flight. For example, the accident pilot was the client’s preferred pilot, whom the client trusted to fly his children.

‘Also, the air charter broker used Island Express exclusively for the accident client’s local helicopter transport needs because Island Express was the only operator that met the air charter broker’s standards for the client, and the client reportedly appreciated the relationship between the two companies. The accident pilot likely took pride in these positions of trust both with the client directly and within Island Express. Further, the pilot’s relationship with the client was friendly, and he likely did not want to disappoint the client by not completing the flight.’

The prestige of being his trusted servant and friend appears to have been subtly corrosive to safety.

‘Kobe was their pride and joy,’ a former Island Express pilot told reporter Jeff Wise of The Atlantic. ‘It was like, “Look at us, we’ve made it”.’

The flip side of this, the former pilot said, was an attitude: ‘You have Kobe on board, you make it happen.’

Tragically, in hindsight, the former pilot said Bryant himself did not necessarily share this attitude. He recalled a conversation he had with the star.

‘Once the weather got to a minimum, I was like, “Hey, I’m not going to be able to make it.” He never once complained.’

The NTSB also listed the lack of an alternative plan and a continuation bias, which strengthened as the flight approached its destination as factors. It found Island Express Helicopters had had ‘inadequate review and oversight of its safety management processes’.

NTSB board member Robert Sumwalt added his own statement to the report. He noted a second pilot could have served as a valuable back-up to the accident pilot’s planned actions and decision-making.

‘Once the helicopter entered IMC, the second pilot could have helped with monitoring and correcting the flying pilot’s control inputs to prevent loss of control. More to the point, however, a second pilot might have provided an important check on the accident pilot’s fateful decision to enter IMC in the first place.’

Sumwalt quoted an NTSB report that analysed 60 helicopter air ambulance flights where pilot acts or omissions led to a crash. The NTSB found that most of these accidents might have been prevented had a second pilot and an autopilot been present.

A second pilot might have provided an important check on the accident pilot’s fateful decision to enter IMC in the first place.

He also called for pilots to subtly rethink the nature of their role.

‘Pilots are, by nature, “can-do” oriented. We want to get the job done, and it is possibly perceived that if we can’t carry out the mission, we have somehow failed,’ Sumwalt said.

‘Perhaps a better way to look at it is that professional pilots aren’t paid to fly – they are paid to say no when conditions warrant. If paid pilots and those who aren’t paid to fly look at it that way, perhaps we will have fewer crashes attributed to get-home-itis.’

Comments are closed.