When you are close to the ground your attention should be focused on flying. So don’t push it, or switch it, or adjust it.

Most times, we have to read accident reports to learn about things that go wrong in aeroplanes.

A tragic crash occurs, an investigation turns up what details are knowable and findings are published. It’s then up to us – pilots and flight instructors – to learn from these conclusions and change our behavior if needed to avoid repeating the crash history.

When the pilot survives a mishap, we sometimes have more information, sometimes less, depending on the pilot’s cooperation. However, where we miss out on learning opportunities is when the pilot is able to recover from the chain of decisions that are building toward an accident, in time to avoid a crash.

In the United States we have a program called the aviation safety reporting system, a voluntary self‑reporting system administered independently of our regulatory system by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The system entices pilots (and other aviation certificate holders) to report on unsafe acts that did not result in a reportable accident, by promising immunity from penalty under certain circumstances if the certificate holder is later cited by the Federal Aviation Administration.

Obviously, Australia does not fall under NASA’s program. But the ATSB investigates and reports on some cases that happily did not end in a crash – giving us a chance to learn from these almost-tragic events. These investigative reports usually include actionable information – things we can do to avoid repeating the circumstances of this crash. You just need to be able to take that information and look further.

For example, consider this ATSB report of a fairly recent chain of events involving a B55 Baron:

On the evening of 13 May 2021, a … Beechcraft Baron 95-B55 … departed Ceduna Airport, South Australia (SA), for a charter flight under the instrument flight rules (IFR) to Parafield Airport, SA, with the pilot and one passenger onboard. During the flight, the autopilot system did not function as the pilot expected.

At 1851, the aircraft was cleared for a night visual approach and descended towards Parafield Airport. At the time, the pilot’s focus was on the autopilot, resulting in the pilot losing sight of the runway and inadvertently overflying the airport towards an area of rising terrain at an altitude well below the minimum safe altitude. The pilot maintained this altitude and continued the approach while looking for the runway. Despite the night conditions, there was enough light for the airport tower controller to see the aircraft and the hillline to the east, so its terrain clearance did not raise concerns.

At 1855, the aircraft re-entered the Parafield control area and was cleared for a visual approach to the runway, landing shortly thereafter.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that during the night visual approach under IFR, the pilot lost situational awareness, probably as a result of distraction due to a perceived autopilot system issue. The approach was then continued at an altitude below the minimum safe altitude, removing obstacle clearance assurance.

What has been done as a result

The operator’s pilot training program has been updated to include a threat and error management course. Airservices Australia advised that Parafield Airport tower controllers would be provided with a briefing paper about the incident and incorporate any learning opportunities and safety messaging from the ATSB investigation. The briefing would include information on the circling area, descent below the minimum safe altitude during visual approaches, go-arounds, and the ‘safety alert’ procedure. This procedure is intended to warn pilots that their aircraft is in unsafe proximity to terrain, obstruction, active restricted/prohibited areas, or other aircraft.

Safety message

Handling of approaches is one of the ATSB’s SafetyWatch priorities. Due to the reduced visibility at night, a night approach requires even greater pilot awareness. Unless there is a problem affecting flight safety, pilots should remain focused on monitoring aircraft and approach parameters, which provides assurance that an approach can be safely completed. If a visual approach cannot be completed, pilots must inform air traffic control so assistance can be provided.

If the criteria for the safe continuation of an approach are not met, for example, losing sight of the runway, pilots must initiate a go-around and attain a safe altitude to reduce the risk of colliding with obstacles or terrain.

Analysis

ATSB did an excellent job of identifying hazards on the regulatory side of this chain of events: don’t go below minimums, if you lose sight of the runway during the visual portion of an instrument approach, go around immediately and inform air traffic control immediately if you find yourself in a bad situation. It took the added step of addressing the air traffic control side of the accident chain, by directing a briefing of controllers on what they might do if they see a potential descent below minimums or detect an altitude deviation has occurred.

I’d like to take this great advice a bit further. What more can we learn from this event?

Looking inward

ATSB summarised its findings as:

… during the night visual approach under the IFR, the pilot lost situational awareness, probably as a result of distraction due to a perceived autopilot system issue. The approach was then continued at an altitude below the minimum safe altitude, removing obstacle clearance assurance.

Put yourself in the cockpit of that Baron and consider what you might have been thinking as the scenario unfolded.

You’re inbound, flying under instrument flight rules in VMC. The last daylight is quickly sliding under the western horizon; from your vantage point you may not be able to make out the ridgeline to the east of the airport very well. The Baron’s cockpit is dim in the receding light and the bright avionics and panel lights – even if dimmed – might further limit your visibility outside the aircraft.

They were so focused on resolving the autopilot issue that they didn’t notice the aeroplane descending below the safe minimum altitude and dangerously close to terrain.

Meanwhile, you have detected, and may even have known about for some time, an issue with the autopilot. It’s not behaving as you expected, which might have been a mechanical or software issue, or could have been the result of the way you programmed it.

An autopilot is a very capable, yet very stupid, copilot. It will very precisely do whatever you tell it to do – whether that’s what you intended for it to do or not. A discrepancy between expectations and outcomes can be very distracting and that’s what the ATSB said happened here (most likely because that’s what the pilot later told investigators).

In a darkening cockpit, with fading outside references that were perhaps obscured by bright panel lights, their reflections off the inside of the windows and their effect on the pilot’s night vision, the pilot’s attention was drawn inward. They were so focused on resolving the autopilot issue that they didn’t notice the aeroplane descending below the safe minimum altitude and dangerously close to terrain.

Altitude awareness is not just an issue for instrument pilots. Any pilot might be distracted or simply mis‑prioritise actions and lose track of their altitude and terrain clearance. Flight in reduced visibility – night flight or in IMC – just make loss of altitude awareness more likely. So, what we can do to reduce the risk of distraction, especially when changing altitudes?

Looking out

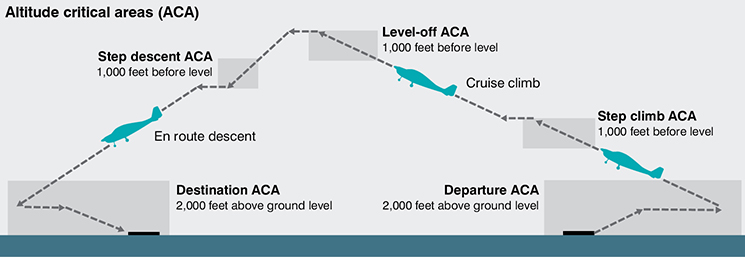

I teach a concept called the altitude critical area (and because, like almost every other pilot, I like acronyms, I express it as one – ACA). An ACA is an area bounded by altitudes – the last 1,000 feet prior to level-off from either a climb or a descent, and anything within 2,000 feet above ground.

There are obvious exceptions but, for the most part, pilots climb to at least 2,000 feet before leveling into cruise flight, so this definition works. I define the ACA specifically for workload reduction and risk mitigation, to prevent precisely the sort of inward-focused distraction that could have cost the Baron pilot and his trusting passenger their lives.

The technique, put simply? Within an ACA, do the minimum necessary to fly the aeroplane through the airspace. Focus on the immediate task of leveling off or, if within an ACA defined by the last 2,000 feet of descent to landing, on only those tasks necessary to safely complete the approach and landing. Everything else can wait.

Don’t try to ‘catch up’ until you’re at least 2,000 feet above ground.

Take-off and climb: For a normal departure, if you don’t have something set before taxiing onto the runway, don’t try to ‘catch up’ until you’re at least 2,000 feet above ground. This technique should make you even better about using pre‑take‑off checklists so you don’t find yourself in this position! If something goes wrong, and you still have the ability to climb, climb above the ACA before attempting to investigate and resolve the issue.

Level off: In the last 1,000 feet of climb, defer non-essential tasks like pre-tuning radios, talking to passengers or programming the GPS until after you’ve leveled off, transitioned to cruise flight and referenced the checklist to ensure you’ve not missed any required actions.

Descent and landing: Similarly, in the last 1,000 feet of an intermediate level off from descent, defer any nonessential actions until after completing the level off. Ensure the aeroplane is ready for approach and landing before descending to less than 2,000 feet AGL, including as many pre-landing tasks as may be done by that time and referring to the checklist to double-check your actions.

Abnormal indications and emergencies: Do not troubleshoot systems or try to resolve discrepancies within an ACA. Stay above or climb out of the ground-based ACA or complete the level off at your new altitude (including checklist actions) if in an ACA defined by top of climb or bottom of descent, before trying to fix anything. If you have an emergency, exit the ACA if the aeroplane is at all capable of doing so. If you note a problem (like unexpected autopilot operation), do not enter an ACA except by abandoning the use of that equipment and proceeding without it.

Back to the Baron

Let’s apply the ACA concept to the Baron at Parafield. The pilot was having some unstated difficulty with the autopilot – it must have not failed completely, because there was enough operability that the pilot appears to have thought they could get it to work properly. The perceived problem may have been not with the autopilot itself, but with its interface with a navigation system – ‘mode confusion’, that is, a discrepancy between what we think we’ve programmed into the navigation/autopilot system and what we actually programmed it to do, is a common issue in today’s tech-heavy cockpits.

Regardless, nearing the destination for a night visual approach, the pilot continued to focus on troubleshooting the autopilot to the extent they let distraction lead to loss of terrain separation and, potentially, an impact that would almost certainly have killed pilot and passenger.

Using the ACA technique, the pilot would have abandoned any attempt to troubleshoot the autopilot when beginning the descent below 2,000 feet AGL. The pilot would have made the decision at that point, well above obstacles, not to continue to try to resolve whatever discrepancy existed and to simply hand fly the visual approach to landing.

Whenever you’re within 1,000 feet of leveling off, or within 2,000 feet of the ground – day or night, either visual or by reference to instruments – eliminate distractions and focus on altitude, airspeed, heading and navigation (aviate and navigate). As the ATSB investigation of the Baron reminds us, the absence of an accident does not necessarily mean that a flight was conducted safely. Use the ACA technique as well as ATSB’s guidance to keep focused outward on what’s most important.

| Further reading: AIP ENR 1.1 2.11 Descent and approach – particularly 2.11.3.5 AIP ENR 1.5 1.6 – Circling approaches and visual circling – particularly 1.6.6 Note 1 |

No mention of the Australian ASRS? What a missed opportunity.

The Australian version of the Aviation Self Reporting Scheme is run by the ATSB and, similar the US version, offers protection from administrative action by CASA in certain circumstances. It’s on the ATSB website under Aviation > Reporting.

Re Tim’s comment. The original ASRS was completely ruined by a determined action to bring a legal action that stripped anonymity from the system. I suspect that many pilots are naturally wary as there is no long standing tradition AND actual known practice to underpin trust across the whole industry.

A fully functioning ASRS is aimed at bringing forth the information that will never otherwise be known except to the participants in events. An ASRS survives on people trusting it completely without but a moment’s hesitancy, if that. Break that trust but once and it will not come back for decades if ever.

Accidents can yield much to learn from and improve upon, an accident avoided can yield far more and the number of incidents that did not result in an accident far exceeds the number of accidents. Most of them we will never learn a thing about except by an ASRS rigorously protected.