Just because something seems reasonable doesn’t mean it is true. It might just mean you want it to be true, as this pilot discovered.

A former boss once warned me that ‘an assumption is the basis of a screw-up’. While I’ve often repeated that maxim to others, it took 5 white-knuckle minutes to teach myself the wisdom of those words.

The weather was ‘severe clear’ that October evening and, with my newly acquired night-flying rating added to my private pilot’s VFR licence, I was looking forward to an hour of circuits to hone my take-off and landing skills. I’d rented a mid-70’s vintage Piper Archer at Buttonville Airport on the northern fringe of Toronto, Canada.

The trouble began innocuously enough during the walk around. The cap on the oil dipstick was screwed on too tight for me to loosen by hand. I flagged down the rental agency’s fuel browser and asked the driver to borrow his pliers. He volunteered instead to take care of the tight cap for me and that’s when I made assumption #1: now that help had arrived, I can continue my walk around.

So, I was busy checking the fuel for water when I heard the driver unsnapping the 4 cowling latches to access the engine. A few seconds later, he cheerfully informed me he’d unfastened the oil cap and the oil level was fine. I thanked him and heard him drop the engine cowling back into place as I was releasing the rear tie-down rope. The driver moved on to his next stop and I got into the aircraft. Without realising, I’d just made assumption #2: the driver tightened the cowling latches.

Eager to get airborne, I pushed the stuck dipstick from my mind and focused on the pre take-off check list. The run-up and taxi to the active runway were uneventful. With no traffic in the pattern, I received immediate clearance for take-off on runway 33.

The altimeter was passing 300 feet and the end of the runway was passing beneath the aircraft when the cowling popped up, held in place only by the loosened latches! Now the cowling was poised like a blade in the windscreen just inches away, rattling and straining against the latches. If they gave way, it would slice through the windscreen like a buzz-saw.

My initial embarrassment at having been so sloppy turned to cold-sweat fear. The cowling was almost completely blocking my view! My first instinct was to reduce power to take the strain off the latches but countless warnings about the dangers of power reduction on take off kept my hand off the throttle.

Besides, I reasoned it was better to get to circuit height to have enough altitude to complete the circuit and get back down on the ground ASAP. I didn’t yet appreciate just how difficult that was going to be.

Instead of the runway, all I could see was a big black square.

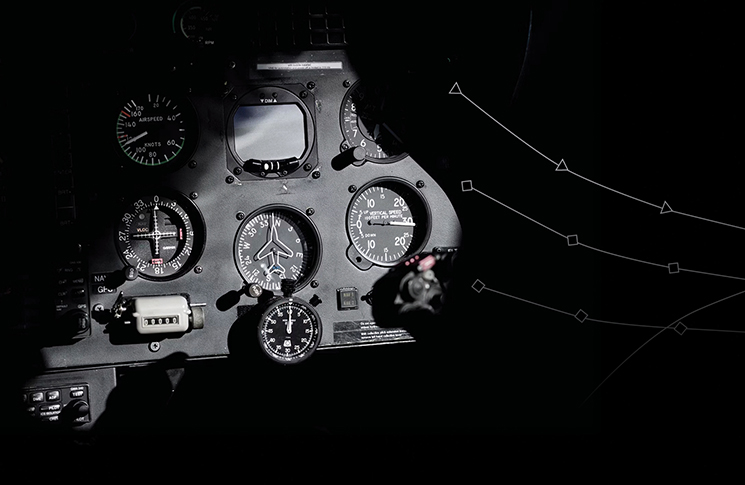

‘Aviate, navigate, communicate’ was the mantra drilled into me at flight school. I forced my attention from the fluttering cowling and scanned the instrument panel. Satisfied the aircraft was operating normally, I gingerly banked it into the crosswind leg. Only then did I advise the tower I had a technical problem and requested a full-stop landing.

Flying almost blind, I followed the circuit pattern by using the runway lights below and the instruments to maintain straight and level flight in the downwind leg. Throttling back to turn base, I prayed the slower speed would drop the cowling. No such luck. Instead of the runway, all I could see was a big black square.

The cowling had risen slightly higher on the right side, exposing a narrow gap between it and the engine. Through this gap I could see about a tenth of what was ahead of me. It was like steering a cargo ship through a porthole. And to see even that much, I had to maintain a nose-down attitude. Once I leveled off into the flare, I’d be blind again. I desperately recalled what my instructors had said about using only peripheral vision to land. I hadn’t thought much about it at the time but now it was all I had.

Figuring that a hard landing on the mains was better than a one-pointer on the nose wheel, I cut the remaining throttle as soon as the aircraft passed over the end of the runway, parked the nose in a slight flare and waited for the aircraft to run out of lift. She took her time but with 4,000 feet of runway, I was more concerned about staying centered between the runway lights. Finally, a gentle thump of the mains and one for the nose wheel.

I taxied back to hangar and by its light, got the hatches securely fastened. I resisted the temptation to congratulate myself on my handling of my first real in-flight emergency. I’d caused it!

Lesson learnt:

The bowser driver happened by while I was paying for the rental. When I told him what had happened, he went a little grey and began apologising. But I assured him it was my fault as PIC to ensure the aircraft was airworthy.

‘And that’s why I didn’t do those latches,’ he said, still apologetic.‘I just assumed you’d want to check the oil yourself.’

Have you had a close call?

8 in 10 pilots say they learn best from other pilots and your narrow escape can be a valuable lesson.

We invite you to share your experience to help us improve aviation safety, whatever your role. You may be eligible for a free gift just for submitting your story.

Find out more and share your close call here.

On day one of air traffic control training I was told “NEVER ASSUME” – it makes an ASS out of U and ME – and I never forgot it and after 30 years of applying it on the job I never assume about anything.

For those who go onto unfortunately experience a open cowling event, try a slip. It just may redirect the airflow to push down the cowling.