Recent la Niña rainfall has amplified a longstanding aviation hazard, as Steve Blackie discovered

We have all been told from our very first flight, how important taking a fuel drain is for the safe operation of our aircraft.

Over the years I have probably taken hundreds of them and never found water in any of the tanks or the carburettor drains I have done. That was, of course, until now. This incident happened at Archerfield this year.

About a year ago, I bought my first aircraft, an older PA-28-140, after flying hire aircraft for more than 20 years. It’s a great feeling to find your aircraft as you had left it. Unless, of course, you have just had more than 600 mm of rain in the last week (or to be more accurate, in 4 days of the last week), as Archerfield had just recently had.

The first thing I noticed was the carpet in the aircraft was wet, along with a cushion on the right seat. During all my years of flying, I had never seen an aircraft get so wet inside from rain.

I started thinking about how the water got into the cockpit when it has a cabin cover – it must have been through the cover’s Velcro on the aerial and door and through the air vents in the wings. With things being so wet, it made me start to think, ‘What else could the water have got into?’

On days when I fly, I aways fill the tanks to the top, as l have always believed having fuel you didn’t need onboard, is much better than not having enough. So each day I do my pre-flight inspection, except for the fuel drain, which I do after a short taxi to the fuel farm and filling the tanks. This always made sense too, as I would be doing the drain after refuelling and before the first flight of the day.

Could it be all water? This was something I had never considered.

While doing the pre-flight inspection, I looked in the tanks and noticed small bubbles on the bottom. I wondered, ‘Is that water in the tank?’ I took a drain from the first tank and it showed no sign of a water line.

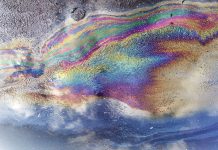

However, I still wasn’t convinced I didn’t have water in the tanks. I took a sample from the second tank which also showed no water line, but it still didn’t look or smell like fuel. Could it be all water? This was something I had never considered – you could have that much water in a tank.

I took drain after drain but still couldn’t smell fuel. I poured it on my hand to see if it felt like fuel – it didn’t seem oily enough. What else could I do? Should I taste it?

I knew what fuel tasted like from childhood when using a garden hose to syphon fuel from my father’s car for my farm motorbike. So I poured some on my hand and stuck my tongue into it and, to my surprise, it was water, all water.

At this point I rang Neil, my LAME for advice, but the call went to voicemail. So I turned on the drain tap and let it run with my hand under it, until it felt, smelt and looked like fuel once again, then repeated this on the other tank.

My phone rang and it was Neil. He came to the aircraft and we shook the airframe and then took drains, each time with less water in the fuel. He confirmed the water had not been picked out of the tanks by the fuel system, by doing a carburettor drain. Then he recommended I do lots of taxiing, followed by draining fuel.

Three hours later, I got into the air safely and all I had lost was flying time.

If I had just started the engine, the fuel system would have been filled with water and the engine would’ve stopped during taxiing. But the worst outcome could have been less water than I had, so still enough pick-up at rotation but stopping just after take-off.

Lessons learnt:

- Always take fuel drains before starting the engine.

- Make sure it’s not all water that you have drained, as you will not see a line between water and fuel.

- What could save your life is knowing the difference between fuel and water. Use your knowledge of fuel’s colour, smell and feel – and maybe even the taste!

Have you had a close call?

8 in 10 pilots say they learn best from other pilots and your narrow escape can be a valuable lesson.

We invite you to share your experience to help us improve aviation safety, whatever your role.

Find out more and share your close call here.

Comments are closed.