An Australian study reveals an unexpected relationship between pilots, personalities and risk-taking, and provides encouraging evidence of discipline by pilots.

Risk-taking and aviation have an uneasy relationship. Taking needless risks is a factor in countless aviation accidents, including inadvertent encounters with instrument meteorological conditions, powerlines, fuel exhaustion and stall speed. Yet, to take off at all, whether in an aeroplane, helicopter or balloon, is to take a risk because all aviation is an act of defiance against the law of gravity.

This apparent paradox has puzzled psychologists for many years. But a recent study1 by Yassmin Ebrahim from the School of Aviation at the University of NSW (UNSW) suggests the difference is in how risk is embraced: the careless scoff at danger or the careful analysis, and measures to mitigate the risks. Her study also suggests that the acceptance of risk involved in choosing aviation is counterbalanced by enhanced caution when operating in aviation.

Method

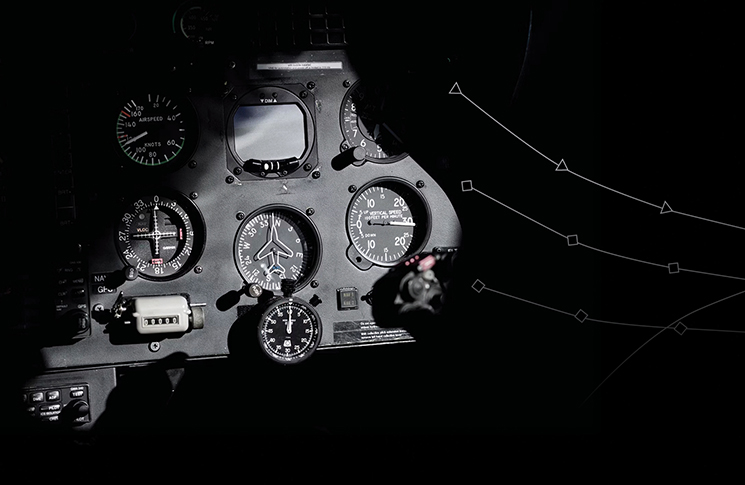

Ebrahim’s study used personality scales to assess 117 participants drawn from pilots at the UNSW School of Aviation and the general university population. The pilots completed an additional 2 scales, unique to aviation, and piloted a flight in a simulator.

The personality scales included:

- Big 5 inventory (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism)

- short test of music preference (STOMP) scale

- stimulating risk-taking and instrumental risk-taking scale

- Zuckerman’s sensation seeking scale (SSS)

- evaluation of visual analogue risk (EVAR) scale.

The 2 risk-based scales for pilots were:

Hunter’s risk perception scale

- other

- self.

The pilots were given a task instruction sheet that explained they were a new employee of a company, who was asked to fly from Orange to Bathurst in NSW, to inspect an unsealed runway and return to Orange. A Frasca flight simulator was configured to replicate a Diamond DA40 single-engine, fixed low-wing aircraft.

External visuals were presented to participants on a 10 m-curved screen using 3 projectors displaying 270-degree field of view. The pilots were not told their altitude in inspecting the runway would be used as a measure of their risk-taking.

Weather for the flight was clear skies and calm conditions and no emergencies featured. The aircraft was considered airworthy at the start of the flight, with sufficient fuel on board for the return flight, including 10 minutes of fuel for the airport inspection and the industry standard of 45 minutes of fixed reserves. On average, the flight took 60 minutes.

Results

Pilots scored higher on the thrill and adventure seeking part of Zuckerman’s scale compared to the general population. Ebrahim says this ‘indicates they are more likely to seek activities involving thrill and adventure’. But pilots also scored higher on the EVAR scale’s self-control factors, indicating they show more self-control than members of the general population in terms of propensity to take risks.

The simulated low-flying spotting task showed a similar paradox. ‘Specifically, pilots who are more imaginative, creative and have an open mind (i.e. scored high on the openness factor in the Big 5) and have high-risk tendencies (scored high on the EVAR scale – total factor), remained at a higher average altitude than their less risky counterparts.’ In other words: actual risk-taking was the opposite of that predicted by personality scales.

A correlation analysis produced another surprising result. Flight experience did not seem to account for acceptance of risky flight behaviour.

Ebrahim’s findings join a small group of research (including a study by UNSW’s Brett Molesworth) that has found, in safety critical professions or in high-skilled, risk-taking sports, that risk-taking propensity is inversely related to risky behaviour.

‘It is plausible that there are 2 distinctly different risk-takers, “impetuous” and “calculative” risk-takers,’ Ebrahim writes. ‘Impetuous risk-takers appear to engage in risky behaviour with little thought or concern regarding the potential for harm. They also view hazards less holistically, thereby underestimating the probability of specific risks, and see themselves as less vulnerable to misfortune. Calculative risk-takers on the other hand, appear to engage in risky behaviour, exercising constraint, thus minimising the potential for harm. They also have an appreciation for the hazard/s, its potential for harm and possess a more realistic view of their ability.’

Ebrahim says the results have important implications for recruitment and selection. ‘Knowing that propensity for risk does not always result in risk-taking behaviour may allow such organisations to reconsider how they use psychometric scales. By extension, a better understanding of these 2 factors should also allow for (more) targeted training and education for existing pilot populations, thereby actively increasing safety.’

Ebrahim says future research should investigate how an individual’s risk propensity and behaviour changes over their career. Another field of study should be how risk propensity and risky behaviour are affected by the risk appetite of an organisation. And she says future research should be directed to better understand the distinction between impetuous and calculative risk-takers.

1 Yassmin Ebrahim, Brett R. C. Molesworth & William Rantz (2022) Risk-taking Propensity: A Comparison between Pilots and Members of the General Population, The International Journal of Aerospace Psychology, 32:2-3, 138-151, DOI: 10.1080/24721840.2021.1978847

I am not sure height in inspecting a runway is as important as the air speed, this latter can kill you but any height from 100 to 500 should be roughly equivalent in safety terms