The phenomenon of dynamic rollover is a (sometimes expensive) reminder that helicopters need expert and careful handling from the moment their rotors start turning.

First Tuesday in November 2013, and racegoers were heading off to Flemington Racecourse for a fun and enjoyable day at the Melbourne Cup. There was a triumph – Fiorente won the race, a tragedy – another horse, Verema, had to be euthanised, and a brush with disaster in an expensive, but thankfully non-fatal crash the last helicopter flight of Cup Day.

The helicopter was a Bell 206L LongRanger which had been conducting flights between Flemington Racecourse and Olympic Park for the Melbourne Cup carnival. For the first flight of the day, the chief pilot accompanied the accident pilot in a supervisory role as they had not done this activity previously.

Once satisfied the pilot knew the procedures, the chief pilot alighted the helicopter and removed the dual controls so the front left copilot seat could be used for passengers.

On removing the cyclic, there is a small moveable flight control stub that is still present below the copilot’s seat on the Bell 206L. This is normally covered with a fixture to prevent a passenger’s feet or heels restricting its movement and hence the cyclic movement. On this occasion, the fixture was not installed. Because the accident pilot was small, a 20-kg ballast bag was required in the front passenger compartment to keep the helicopter within longitudinal centre of gravity (CoG). This was placed on the floor in front of the exposed cyclic stub.

The pilot conducted flying throughout the day, taking a break for lunch and to refuel. On the last flight of the day, the pilot was to go from Olympic Park to Flemington Racecourse to pick up the remaining racegoers and fly them out in style.

A marshaller indicated for the helicopter to wait on the ground while another helicopter landed close by. The marshaller then signalled for the pilot to lift off and manoeuvre to the departure area. The marshaller saw the helicopter lift off momentarily and drift right before the right skid touched the ground and the aircraft rapidly rolled over to the right. The helicopter self-destructed as the main rotors hit the ground, sending parts flying.

Fortunately, there was no post-accident fire and the pilot could exit the helicopter through the now broken front windscreen. Each helicopter parking spot was covered in matting that had been used many times previously. After the accident, this matting was inspected and found still to be held down by its retaining pegs.

Dynamics of a tumble

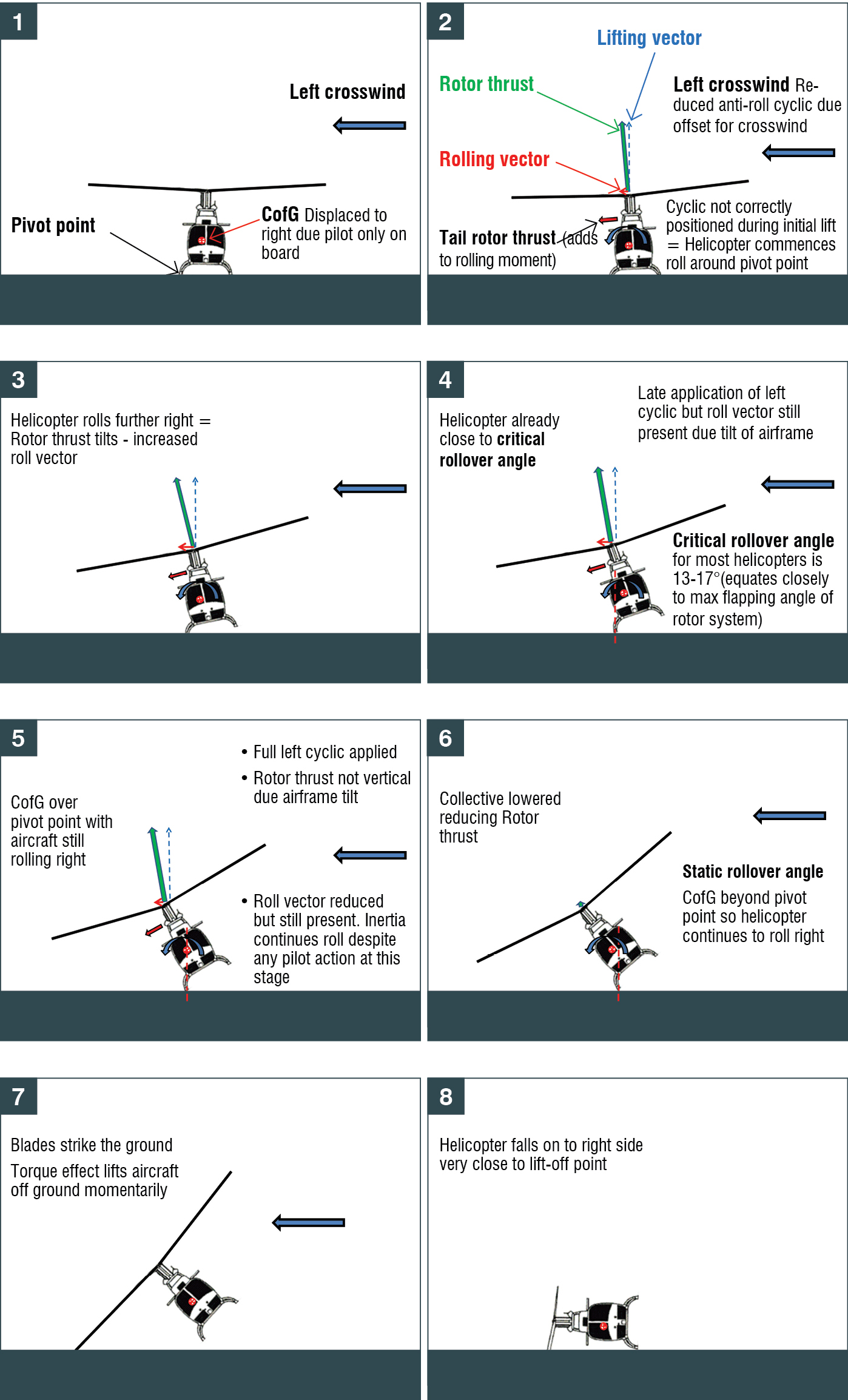

The diagram from the report by the Australian Transport Safety Board (ATSB) shows a generic series of events related to dynamic rollover.

Static rollover Tipping a helicopter sideways on its skid or wheel – undercarriage – will eventually get to an angle where the CoG is directly above the undercarriage that is still in contact with the ground. Any further sidewards tilting than this and the helicopter will fall over on its side, as the CG is now outside the lateral undercarriage track. This is a simple geometric angle that can theoretically be calculated and will vary only slightly depending on the lateral CG of the helicopter.

If you were to park the helicopter on a slope greater than this critical angle, the helicopter would tip over even if the rotors were not turning. However, this doesn’t often occur as you would probably run out of control power or rotor disk deflection to get the aircraft to this angle. Mast bumping, droop-stop pounding, mast bending moments or even the cyclic being restricted by the pilot’s leg would normally stop you parking a helicopter on a slope, at or past its critical static rollover angle.

Dynamic rollover

This occurs at much lower angles than the static rollover critical angle. Furthermore, this angle varies, as it depends how much the rotor disk is being tilted and how much momentum the rotating helicopter fuselage has generated about the undercarriage that is still in contact with the ground.

In dynamic rollover, the rotor thrust – if tilted away from vertical and the side component of this thrust – creates a rolling moment around the undercarriage that is on the ground. Specifically, this is the undercarriage that the horizontal component of thrust points to. This rolling moment is what tips the helicopter over. The opposing rolling moment countering this is the weight of the helicopter acting through the CG about the undercarriage that is on the ground.

Dynamic rollover can happen so quickly that recovery actions may be impossible.

The higher the aircraft tips, the closer the CG comes to being over the undercarriage on the ground and the less restorative moment that the CG provides to counter the moment generated by the horizontal component of the tilted disk. As the helicopter moves, it gains momentum and there comes a point where the pilot cannot stop the aircraft from rolling over, no matter what they do with the cyclic or even collective. This angle cannot be defined as there are too many variables; however, it is less than the static rollover critical angle and, in most cases, significantly less.

Factors to watch

Some other factors can make things worse for dynamic rollover. Crosswind and tail rotor thrust can provide forces that help generate a rolling moment that makes the problem worse. The thrust generated by the tail rotor also means one side of the helicopter will hang lower than the other to prevent the helicopter drifting – tail rotor drift.

Manoeuvring too close to the ground and catching a skid or wheel with a sidewards motion will also generate a rolling moment due to the momentum of the helicopter now generating a rolling moment around the undercarriage touching the ground. In this accident, these factors contributed to the dynamic rollover.

If you can identify that dynamic rollover is occurring, the best solution is to rapidly lower collective to reduce the thrust vector.

Taking off on muddy or icy ground or sticky asphalt can mean the undercarriage is stuck, and one side will release before the other, generating a rolling moment. Tie downs or items hung off the undercarriage can also generate moments on take-off that lead to dynamic rollover. Poorly executed slope landings and take-offs can also be dangerous.

Balancing on one skid or wheel and overcontrolling can lead to an upslope rollover, with excessive into-slope cyclic being applied, or a downslope rollover where the aircraft is dropped or lowered too quicky onto the downslope undercarriage and the momentum generated rolls the aircraft over.

The accident report also discussed how the ballast bag could have interfered with the cyclic stub. The ballast bag may have moved after lift-off and momentarily restricted the cyclic. This may have restricted the pilot applying correct cyclic on lift-off to counter drift. Although not specifically stated as an accident cause, loose items on the cockpit floor are not conducive to safe flight.

The cyclic may also be restricted by the pilot’s leg. When doing slope landings, the collective will be in a high position and, for left upslope landings, the cyclic will be displaced to the left to pin the upslope undercarriage. Pilots with large thighs can find the leg prevents them getting enough cyclic displacement or their leg must rest up against the collective, preventing small smooth collective adjustments. This can result in overcontrolling which may contribute to a slope landing dynamic rollover.

Some pilots in some wind and slope conditions may not be able to get to the flight manual slope landing limit due to interference from the collective, left leg and cyclic. In this situation, the aircraft roll rate may not be able to be controlled due to collective interference with the leg – the aircraft will gain rolling momentum as it lowers and can tip over the downslope undercarriage.

The best means of recovery from dynamic rollover is not getting into the situation in the first place.

Recovery

The best means of recovery from dynamic rollover is not getting into the situation in the first place. As soon as the rotor is turning, the helicopter is flying and smooth deliberate control of the rotor disk is always required. As collective is applied, the cyclic needs to be adjusted continuously to maintain a level fuselage attitude. This will ensure there is no tendency to generate excessive horizontal force from the rotor that could roll the helicopter over or generate a drift on lift-off that causes the undercarriage to catch on the ground and generate a rolling moment.

Lifting off on icy or muddy ground or sticky asphalt may require small fore-aft rocking or yawing of the helicopter to ensure the undercarriage is not stuck to the ground. Small gradual increases in collective with adjustments to cyclic will prevent any surprises. Rapidly trying to lift-off will lead to reduced notification of poorly set cyclic or stuck undercarriage. Dynamic rollover can happen so quickly that recovery actions may be impossible.

If you can identify that dynamic rollover is occurring, the best solution is to rapidly lower collective to reduce the thrust vector. If you are balancing one undercarriage on a slope, you need to be careful of thumping down the other undercarriage and rolling over, down slope. Using the cyclic to control roll rate normally isn’t sufficient as there isn’t enough control power to reduce the rolling moment and move the aircraft back to the level attitude quickly enough.

There can be talk of trying to fly the helicopter out of the impending dynamic rollover. This is probably only a viable option when doing a slope landing and you realise the slope is too large or you are starting to let down the airborne downslope undercarriage too quickly.

Aborting the landing and lifting off into a hover clear of the ground is a safe way of preventing the start of dynamic rollover from occurring. You can now reposition for more favourable conditions. However, thinking that you can fly out of a dynamic rollover situation on take-off is probably not going to improve the situation and is most likely going to make it worse.

Dynamic rollover is a fast onset dangerous situation that is best avoided by ensuring the helicopter is not placed in that dangerous situation in the first place. Constant attention and small incremental adjustments to the flight controls on take-off and landing will ensure the pilot is not surprised by a sudden rollover that turns a fun day out at the Melbourne Cup into a dangerous situation on the way to the racecourse.

Dynamic rollover sequence

Comments are closed.