It isn’t just houses and businesses that fell foul of the recent flooding and torrential rain plaguing Australia’s East Coast – aircraft also were caught.

The question then is whether to write off an aeroplane affected by water immersion or make repairs.

Unlike cars, there is no statute preventing an aeroplane written off by an insurance company from being repaired.

Owners can take the payout, buy back the damaged aircraft and get it fixed, although certain manufacturers may issue a service bulletin identifying aircraft they no longer support because they have been submerged.

However, Flight Safety Australia was told most manufacturers don’t do this and in many cases there was nothing to stop a flood-damaged aeroplane being returned to service.

It’s not clear how many aircraft fell into this category after the recent floods but a number of areas in Queensland and New South Wales were affected.

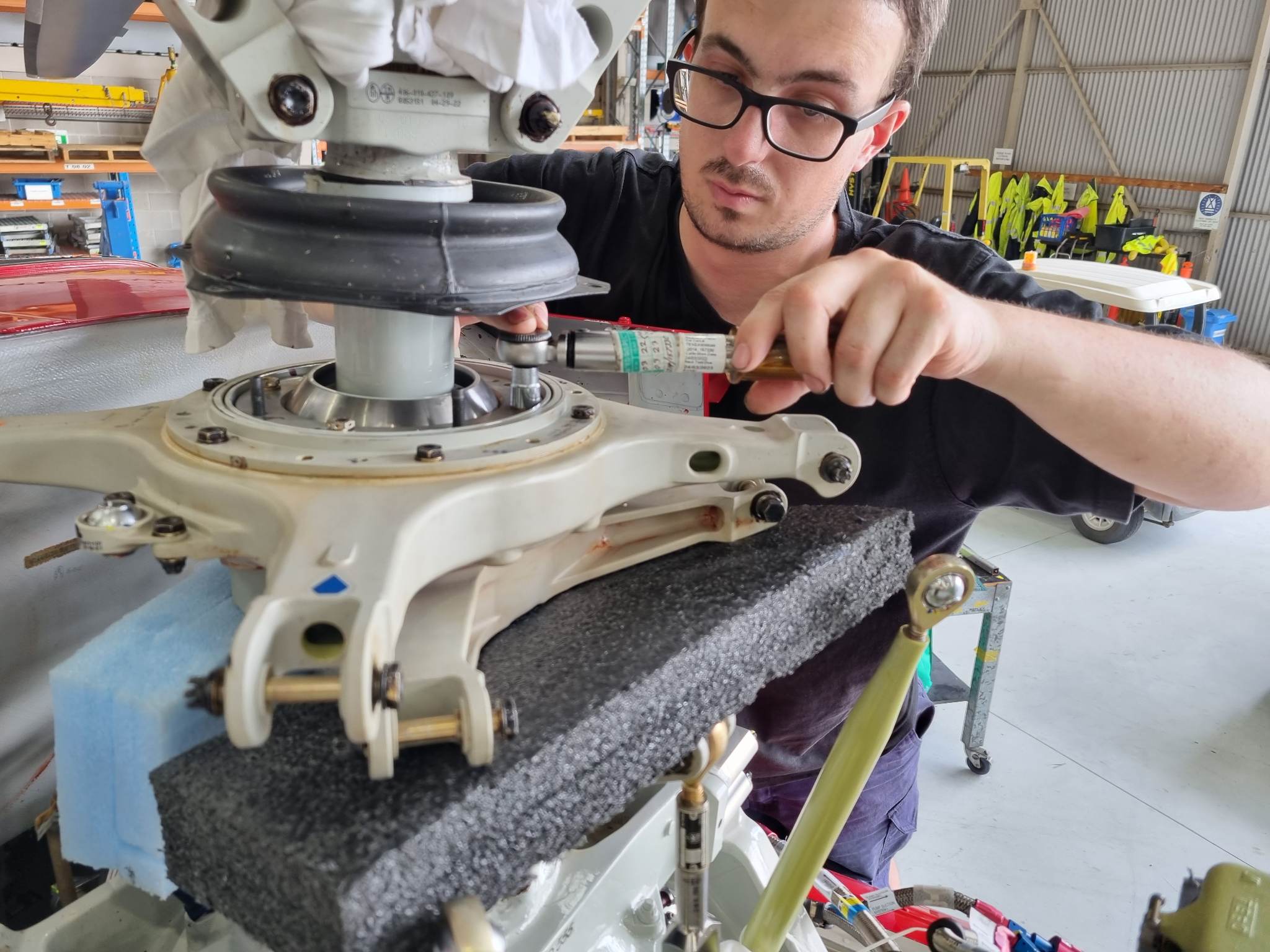

However, returning an aircraft that has been submerged to service and doing it properly is neither easy nor cheap.

What owners should not attempt to do is hose out an aircraft and start it up again, according to CASA Acting Principal Airworthiness Engineer Gustav Anderson.

Anderson said it was necessary to remove anything that could possibly corrode an aircraft as quickly as possible – one manufacturer puts the limit at 5 days – as well as replace many components.

‘Some of them will be a total rebuild, looking at a year or so,’ he said, noting aircraft damaged in the most recent floods would likely be rebirthed, repaired or parted out.

Anderson and colleague Peter Gibbs have issued airworthiness bulletins (AWBs) outlining the steps that should be taken to return aircraft to service where manufacturer guidance is not available.

One bulletin deals with airframes, components such as avionics, propellers and motors, as well as systems such as hydraulics and fuel.

The other deals with an aircraft’s engine or engines.

Important factors include the level of flood waters, whether the water was fresh or contaminated and how long it takes before the repairs can begin.

The AWB notes that the longer it takes to extricate the aircraft and assess the damage, the greater the likelihood the water and its contaminants will migrate into components and assemblies.

There is a need to move quickly to clean the aircraft, perform interior and exterior inspections, remove corrosion and apply protective treatments and finishes.

‘A significant number of component/parts may need to be replaced as water serves as an electrolyte that promotes corrosion,’ the bulletin says.

‘The corrosiveness of water depends on the dissolved minerals, organic impurities and dissolved gasses, particularly oxygen, in the water.’

And fresh water may not be as fresh as you think – CASA’s experts say it varies between localities and depends on factors such as the dissolved impurities and the presence of chlorine and fluorides.

The AWB emphasises that inspections should be performed in the first instance according to manufacturer’s recommendations or the operator’s maintenance program.

These take precedence over recommendations in the bulletin, which should only be applied to aircraft where the manufacturer has not published information.

However, where there is no manufacturer information, the document recommends a list of actions related to the airframe as well as various components and systems.

This includes removing interior components to expose the aircraft structure and, where necessary, removing flight controls such as the wings, rudder, elevators and horizontal and vertical stabilisers.

Subcomponents such as mechanical actuators, bell-cranks and pushrods may also need to come out.

All internal and external areas of the aircraft should be washed using approved water-detergent solution or water-emulsion cleaning compound MIL-C-43616.

All areas should be thoroughly washed with potable water and a corrosion inhibitor applied where necessary.

Components likely to need replacing include bearings, wiring bundles and electrical components, while control systems should be cleaned and lubricated. Hydraulic and fuel systems need to be flushed.

The second AWB details what needs to be done in terms of engine inspections.

It warns that moisture or foreign materials can cause damage to all systems of an engine immersed in water and this can remain hidden as it develops over time.

Again, so-called fresh water may not be what it appears. Salt, in particular, is the enemy in terms of corrosion.

As with other parts of the aircraft, the advice is to follow manufacturers’ recommendations where possible.

The engine should be ‘bulk-stripped’, disassembled to enable the visual inspection of all internal parts for contamination and condition, by an approved organisation.

All areas of the engine and associated parts should be cleaned using approved methods and substances, especially areas where debris and silt can get trapped, and a thorough inspection carried out before it is reassembled.

Full details can be found in the AWBs.

The bulletins are part of a wider service by CASA that provides crucial Airworthiness Directives (ADs) and AWBs produced locally as well as from overseas jurisdictions such as the European Union Aviation Safety Agency and the US Federal Aviation Administration.

‘There are about 8 in the team and we look after everything that’s in service from a continuing operational safety perspective,’ said David Punshon, the manager of continued operational safety at CASA’s Airworthiness & Engineering Branch. ‘We’re also involved with minimum equipment lists, permissible unserviceabilities, maintenance programs and the like.’

Comments are closed.