John Laming on weather radar and its modern low-cost imitator, the electronic flight bag (EFB)

Number 34 Squadron at Canberra operated two Convair 440 Metropolitan aircraft when I arrived in early 1963. One had airborne weather radar and the other didn’t.

I soon learned that A96-353, the Convair with radar, was the favoured of the two aircraft among our crews because it was relatively easy to ‘see’ thunderstorms ahead and avoid them. With A96-313 which did not have radar, you simply crossed your fingers and flew blind, hoping you would miss any thunderstorms that happened to lie in wait on your route. If only we had an EFB to ‘see’ the weather—but they were 50 years in the future.

Thunderstorms are a serious hazard, regardless of aircraft size or performance. In the excellent and still relevant, Handling the Big Jets, DP Davies gives a vivid description of what it’s like to inadvertently encounter one:

We encountered the most violent jolt I have ever experienced in over 20,000 hours of flying.

I felt as though an extremely severe positive, upward acceleration had triggered off a buffeting, not a pitch, that increased in frequency and magnitude as one might expect to encounter sitting on the end of a huge tuning fork that had been struck violently. Not an instrument on any panel was readable to their full scale but appeared as white blurs against their dark background.

From that point on, it could have been 10, 20, 60 or 100 seconds, we had no idea of attitude, altitude, airspeed or heading. We were now on instruments with no visual reference and continued with severe to violent buffeting, ripping, tearing, rending crashing sounds. Briefcases, manuals, ashtrays, suitcases, pencils, cigarettes, flashlights flying about like unguided missiles.

The first officer and I acted in unison applying as much force as we could gather to roll aileron control to the left. The horizon bar started to stabilize and showed us coming back through 90 degrees vertical to level flight. The air smoothed out and we gently levelled out at 1500 feet.

In 1954 two Royal Air Force Canberra bombers were to fly from Australia to Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The flight was shrouded in secrecy. At the time, the Americans were using the remote atolls of the Marshall Islands for atomic bomb testing. The first RAF Canberra disappeared between Manus Island, north of New Guinea, and Kwajalein. No trace of it was found—the consensus being the aircraft went out of control in a thunderstorm. The intertropical front weather system in the Central Pacific region is characterised by violent thunderstorms topping 60,000 feet.

A replacement Canberra flying the same route ran into thunderstorms from which it survived, only to force land short of fuel on a remote atoll 75 miles from Kwajalein. The Canberra was not fitted with an automatic pilot or airborne weather radar. Pilots had to hand fly the aircraft for several hours at high altitude.

From the pilot’s report:

After about 90 minutes at about 45,000 ft, we ran into an intertropical weather front and experienced violent turbulence. We were still in cloud at 50,000 ft, then within 30 minutes both No. 2 and No. 3 inverters failed.

This left me with about 20 minutes of full instruments before we would have to revert to the primary instruments (no artificial horizon). A decision to remain at height or descend had to be made. Descending would mean we would have a fuel shortage, but by staying at height, the heavy turbulence could mean loss of control. We descended in cloud and suddenly palm trees flashed past the wings and we were over an atoll. We circled with flaps and wheels down and landed on the reef in about 8 inches of water and rolled about 500 yards. Some natives arrived from another island (ours was uninhabited) and during our four days they were most helpful.

While the possibility of airframe structural failure due to turbulence is remote, there is evidence that a contributory cause of aircraft break-up in severe turbulence is over-controlling by the pilot during attempted recovery. This may have been a factor in the crash of a Vickers Viscount at Sydney in November 1961. That aircraft penetrated a severe thunderstorm shortly after take-off, broke up in mid-air and crashed into Botany Bay. It was not equipped with weather radar. Following that accident, a requirement was published for this equipment to be fitted to all Australian turbine-powered aircraft.

Improvements in electronics since those dark days have made avoidance of severe weather safer and easier.

Avoiding severe weather

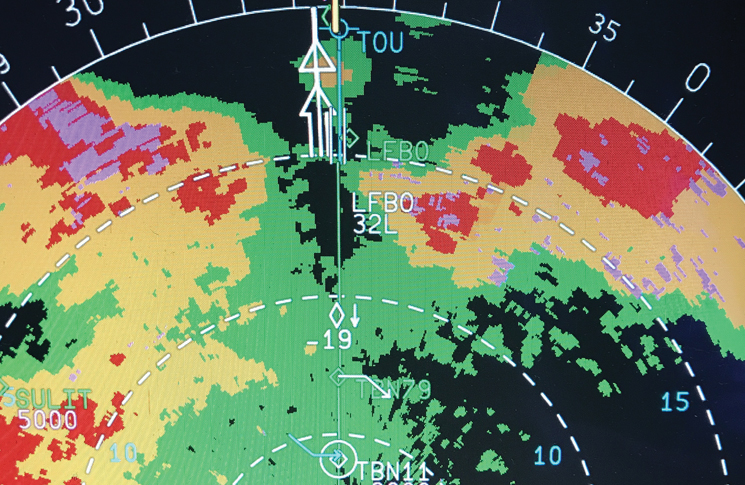

Improvements in electronics since those dark days have made avoidance of severe weather safer and easier. Modern weather radar, such as Rockwell Collins Multiscan, can scan 320 miles ahead to give early warning of potential storms. Remember that thunderstorm clouds can top 70,000 feet and should be avoided by at least 20 miles.

MultiScan radar emulates an ideal radar beam by taking information from different radar scans and merging the information into a total weather picture. Whether or not an aircraft has obsolete or modern sophisticated radar, it is still individual pilot skill in interpreting the radar picture that is important to the safety of the flight.

Electronic flight bags mimic many of the functions of weather radar but are significantly different in how they operate. As these came after my flying career, I spoke about them to Bevan Anderson, founder of AvPlan EFB. Both OzRunways and AvPlan software provide a useful and economical alternative for aircraft that do not have weather radar. Pilots can view en route actual and forecast destination weather including precipitation, turbulence, lightning and icing.

With an EFB, there is a time delay which is predicated on updated information published by the Bureau of Meteorology. For example, the BoM rain radar updates every 10 minutes, meaning rain intensity viewed on the EFB is basically 10 minutes old. Lightning is displayed within several seconds.

For pilots wishing to view current rain/weather information beyond that displayed during flight planning, a source of mobile coverage will be required. Generally, flying at low to mid-levels, one should be able to receive 3G or 4G coverage on mobile devices.

Battery life is largely dependent on usage. There are several ways to control/conserve battery drain on an EFB. The most common are reducing screen brightness and operating in flight mode when additional information is not required.

Four to five hours of usage should be available without an additional power source. This is limited to the age and condition of the EFB. It is strongly recommended that a battery power bank or a source of power is available, for example, from a cigarette lighter.

It should be kept in mind that flying significant distances over water without mobile coverage will result in no signals.

In all cases airborne, weather radar is the prime means of avoiding hazardous thunderstorm weather. An EFB is purely an adjunct to weather radar. However, for a subscription of about $100 a year, the software gives access to valuable data—a situation I would have given my eye teeth for all those years ago in the Convair without radar.

There are still some small general aviation cargo aircraft in Australia that do not have radar and fly cross-country IFR at night—which would terrify me. Today it is unheard of to fly an airliner with an inoperative radar.

John Laming is a former RAAF and airline pilot, with experience on the Mustang, Avro Lincoln, Boeing 737 Classic, and many other types over his 23,500 hour career. He works as a simulator instructor

Comments are closed.