Planning a flight into a remote area this summer? Proceed with caution, lots of planning and with enough equipment to survive any misadventure.

By Nick Stobie

Remote flying amplifies the consequences of making mistakes when operating aircraft—help is further away when things go wrong.

The conditions are harsher, with extreme temperatures and little natural shelter. Terrain can be featureless, making it difficult to position fix and navigate. Natural water is sparse. Radio coverage is limited, with surveillance coverage improving but still yet to cover some parts of the country.

Most of these consequences can be largely mitigated with a bit of planning and preparation. When researching this article, I reviewed incidents in outback Australia where pilots had become stranded after forced landings. I wanted to learn more about which parts of their preparation really made a difference when things go awry. One recent story stood out.

Stuck on Lake Eyre

When David Geers set off in his amphibious SeaRey aircraft for Lake Eyre in remote South Australia in March 2015, he certainly wasn’t intending to get stuck.

After refuelling at Innamincka, his and another SeaRey departed west, destined for William Creek. Their planning determined they had sufficient fuel to make the flight with reserves; however, they had also considered the contingency that stronger than forecast winds might slow the journey.

The other aircraft carried an additional 30 litres in bladders—with only one person onboard—and, after experiencing stronger headwinds, David realised they would have to use the extra fuel to maintain reserves.

They decided to make a precautionary landing on the dry surface of the lake to transfer the fuel. David’s SeaRey attempted the landing first and, although on initial touchdown the surface seemed firm, as the aircraft decelerated the wheels broke through the crust. The aircraft became bogged immediately but was otherwise undamaged. The other SeaRey pressed on to William Creek.

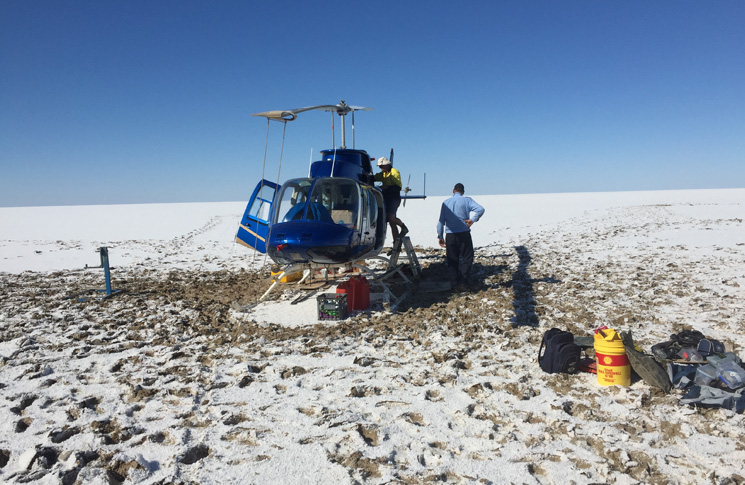

The ensuing rescue attempt went spectacularly wrong and made national news. First, a helicopter was sent to the rescue. It landed on the lake but experienced an engine overtemperature on shutdown and became grounded. Another rescue helicopter arrived much later into the evening, retrieving David and the other helicopter crew, but leaving his SeaRey and a Bell LongRanger stranded.

In the coming days a new engine was flown out for the stricken helicopter, and a plan formed to retrieve David’s SeaRey under the sling load of another LongRanger. However, when lifted by the sling, the SeaRey began to oscillate under the aerodynamic loads and began to fly, threatening the helicopter’s safety.

The helicopter pilot decided to release the amphibious aircraft. Initially it made a graceful descent but then dived into the lake surface, only a few kilometres from the original landing site. It appeared the aircraft would remain as a relic in the outback; however, several months later the wreckage was salvaged by another helicopter and taken to William Creek.

So that day in March 2015 was, all around, a pretty bad one for David. Things could have been a lot worse, but through some good preparation and a little luck to deal with the items he didn’t prepare for, he survived to tell the tale.

Flying remote starts with the basics

First—and most important—the obligations of any other flight apply to remote flying.

Check the weather. Make sure you’ve got more than enough fuel, and then some more. Make sure you are competent on the aircraft you’re planning to fly. Check the aerodrome you want to fly to is suitable and you have permission to land there.

If you need fuel at a location, you must check it is available—before you land there without the option to go elsewhere. You also need to carry an emergency locator transmitter (ELT), emergency position-indicating radio beacon (EPIRB) or personal locator beacon (PLB) as you are likely travelling more than 50 nm from your departure point, but more on that later.

CASA’s Out-N-Back series has some fantastic resources that cover the practicalities of remote flying, a must read for pilots new to navigating outback Australia. The series also covers SARTIMEs and filing flight plans, crucial elements of any outback adventure by air.

What do you need to survive?

Beyond the basics, CAO 20.11 requires that aircraft flying in designated remote areas carry ‘survival equipment for sustaining life appropriate for the area being overflown’.

What constitutes survival equipment is not mandated; however, ERSA EMERG 4 Survival suggests some items. The equipment should be specific to where, what and how you’re flying. It might be as simple as a few extra items for a short flight close to the safety of a major road or highway, or it might be a full multi-day survival kit with flares and rations if you’re really going off the beaten track.

When I spoke to David Geers, he immediately volunteered the key element of survival equipment he didn’t have enough of—water.

He knew immediately after landing he was in a lot of trouble

In March, Lake Eyre is hot. Add to that an absolute lack of shelter, and water becomes the critical thing you need. ‘[We] couldn’t see the edge of the lake—it was 360 degrees of white,’ David says. ‘The only thing that blocked your vision was the flies.’

When the first rescue helicopter arrived several hours later, David estimated he drank five litres of water on the spot. ‘I was amazed how much water we drank. It was an interesting thing, how quickly we became thirsty.’

David and his passenger also had only a little food—an apple and a few chocolate bars. ‘I’ve never enjoyed half an apple so much in my life,’ he says. ‘We could have picked up more water and food in Innamincka than we did—[it was] a mistake that we didn’t.’

Survival time without water varies but most sources will cite two to three days in normal conditions. It would have been shorter on that hot March day on Lake Eyre, which really underscores, above all else, the importance of carrying adequate water for those 24 or more hours you might spend waiting for rescue.

Asking for help

Speaking of rescue, it’s important you can tell the right people you need it. As he should have, David was carrying a PLB.

He knew immediately after landing he was in a lot of trouble. He accurately described his situation to me with an expletive. Thankfully, the other aircraft proceeded to William Creek and raised the alarm. David also managed to raise an overflying airliner on VHF radio. ATC then knew about his predicament, but that by no means got him out of the woods.

Despite an evidently dire situation, David was still hesitant to activate his PLB, which he had conveniently sewn onto his lifejacket. This device is a small, portable version of the traditional ELT installed in many aircraft. In most aircraft, it can be carried instead of an ELT, provided it is in an accessible location. David’s first thought when he reached for his PLB was, ‘This is going to cost me a lot of money.’ However, activating his beacon had the opposite effect.

By activating it, David directly enlisted the assistance of the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA), which coordinates search and rescue services in Australia. The costs of these searches are borne by each state or territory and, therefore, when the beacon was activated, David would not be held liable for the costs associated with his rescue.

More importantly, a PLB with built-in GPS provides AMSA with position information by satellite, accurate to within 100 metres—critically important when searching for a 10-metre-wide aircraft on the 9500 square kilometres of Lake Eyre.

In aviation, we are often reluctant to ask for help. In David’s case, the worry was cost. Others worry about pride or inconvenience to others, or some simply downplay how serious their situation might be. Whether it is by phone, radio or through activating an ELT, pilots should never hesitate to ask for help when they need it—and remote flying is no exception.

In addition to his PLB, David also carried a SPOT Satellite Messenger, a small handheld device capable of sending a pre-programmed message to telephone or email addresses. As a result, David’s wife got the message that he was ‘in trouble but ok’ and his location, before AMSA could even contact her.

Satellite tracking and messaging devices, such as SPOT, Spidertracks and V2Track, are becoming more popular because they provide an additional blanket of security and safety over just carrying an ELT. Although not without cost, they are options worth investigating for those looking to explore remote Australia.

Mere misadventure

David’s story is adequately summed up by the word misadventure. He made a mistake in trying to land on Lake Eyre. He had what he needed to survive. He could send for help. He was rescued, eventually. He did go on to rebuild his beloved SeaRey and still flies it today. But, under different circumstances, tragedy was a conceivable outcome.

When we plan for the worst, often mere misadventure is the best outcome on offer. It makes planning for the worst an inherently unpleasant process. Perhaps that’s why we sometimes overlook refilling those spare water bottles, picking up those extra supplies or investing in that extra piece of emergency equipment like a satellite messenger.

So, when you take your remote adventure this summer, spend those few extra minutes to really consider what you might need to survive for a day or two without help. It might not be much. It might be as simple as plenty of water and a little bit of food.

Check your ELT and consider the other options available to send for help. In doing so, you’ll be confident that the worst thing waiting after an accident is a little embarrassment and inconvenience—and hopefully a good story to go with it.

A PLB with built-in GPS provides AMSA with position information by satellite, accurate to within 100 metres

*CASA’s Out-n-Back 2 pack has a 96-page book and 10 videos that follow two aircraft on an epic 6000-kilometre trip through some of Queensland’s most isolated locations.

Order your hard copy at: shop.casa.gov.au

Or access it online at: outnback.casa.gov.au

Comments are closed.