A Virgin Australia ATR 72 crew’s attempt to take off from the wrong runway at Canberra Airport exposed several procedural and human factors issues, the ATSB report into the incident has found.

On the evening of 25 September 2019, the ATR crew received clearance to line‑up on runway 35 from intersection Golf. The intersection was a short taxi from where the ATR was parked at the terminal and on the brief journey the crew ran through the before take-off checklist. This was a challenge and response procedure, and the investigation concluded it would have required some of the captain’s attention.

After waiting at the holding point for clearance, and having its stop bar deactivated when clearance was received, the crew inadvertently lined-up on runway 30, which also joins intersection Golf. Canberra Tower noticed and commanded the aircraft to stop, just as it was in the early stages of its take-off roll. Engine torque only reached 17.7 per cent. The aircraft stopped and lined up on the correct runway 35, where it took off without incident.

The report found runway and taxiway lighting had made a misinterpretation possible. Lead on lights to both runways 30 and 35 had been illuminated.

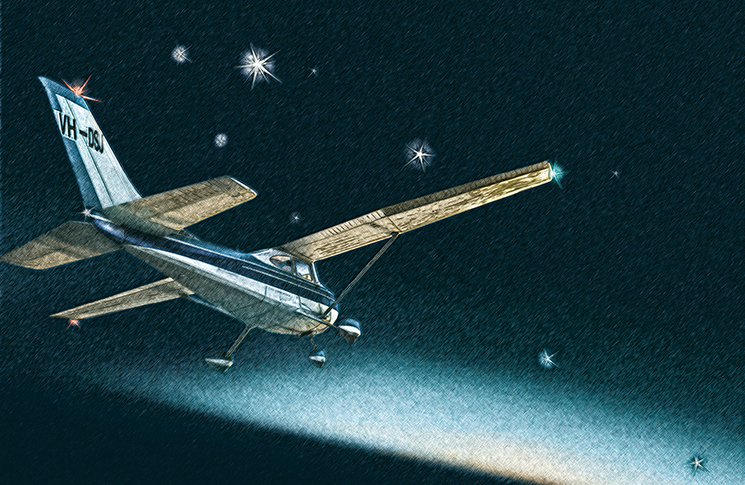

‘This increased the risk of an aircraft being manoeuvred onto the incorrect runway, particularly at night and/or in low visibility conditions,’ it says.

Neither pilot could remember if they had checked the aircraft’s heading after line-up.

Runway 30 is considerably shorter than runway 35. Simulations conducted by Virgin Australia found the take-off could have been successful if the departure had been continued from runway 30.

‘However, a runway overrun would have likely occurred if there was an engine failure at around their selected V1 speed, or if there was any mishandling of the take-off,’ the report said.

Runway selection errors have had disastrous consequences. In 2006 Comair/Delta Connection flight 5156 crashed after the crew lined up on the shorter runway at Lexington, Kentucky in the US. The first officer, who was pilot-flying, was the sole survivor of the 50 people on the CRJ-100 regional jet. Other crashes, such as the failed take-offs of Northwest Airlines flight 255 in Detroit, in 1987, and Spanair flight 5022 in 2008, highlight the hazards of split attention between taxiing and completing checklists (or not completing checklists in the case of these two tragedies).

The ATSB identified the timing of the before take-off checklist as a safety issue in the Virgin incident. There was no requirement to have completed this checklist before reporting ‘ready’ to air traffic control and this increased the risk of flight crews completing this procedure while entering the runway, the report found, diverting their attention to checklist items at a time when monitoring and verifying was critical. The first officer’s attention had been within the cockpit as the captain steered the aircraft on to the runway.

The ATSB also found Virgin Australia did not require flight crew to confirm and verbalise external cues such as runway signs, markings, and lights to verify an aircraft’s position was correct prior to entering and lining up on the runway. Verbalising and pointing has been shown to be effective in reducing error rates and is a widely followed practice in Japanese railways.

Virgin Australia introduced a requirement for the before take-off checklist to be completed before crews report ready for take-off. And for the final few months before ATR 72 operations ceased due to the economic effects of COVID-19, the airline shunned intersection Golf at Canberra. All performance platforms on the ATR 72 were updated and the Canberra ‘TWY G’ intersection departure was removed.

Such a great strategy. Always covers down to simple things sacrificed for profit margins.

Finish checklists.

Verbally confirm runway/headings etc.

It is so good to have these reminders (for an inexperienced pilot like me) from an example that didn’t have causalities.