As our national airline celebrates 100 years, here’s a special gift to avgeeks everywhere–the inside story of the famous ‘roo in the sky

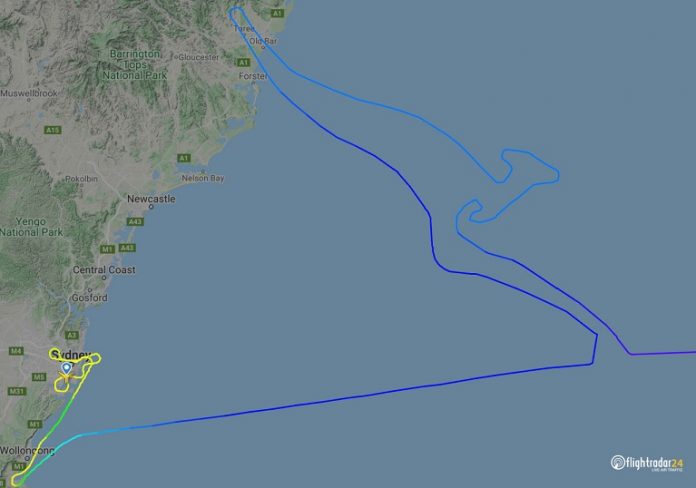

Many years from now, when the brunt of the coronavirus pandemic is over, we’ll still be talking about one of 2020’s aviation highlights—how, on a spectacularly sunny July day, people across the globe were transfixed by a Boeing 747’s final flight as it created a colossal, connect-the-dots ‘flying kangaroo’ over the Pacific Ocean.

It was a parting and nostalgic love letter of sorts, a farewell to all those aviation enthusiasts who followed its final journey online as it flew to the aircraft boneyards of the Mojave Desert.

Headlining this brilliant achievement was Qantas’ Boeing fleet manager, Captain Owen Weaver. The 25-year company veteran is unsurprisingly humble about his flying successes and acknowledges that the feat was ‘absolutely not achievable on my own’.

It’s thanks to Owen and the rest of the QF7474 crew—Captain Sharelle Quinn, Captain Ewen Cameron, Captain Greg Fitzgerald, First Officer Quin Ledden and Second Officer Owen Zupp—that the memorable piece of ‘sky art’ will live long in our collective avgeek memories.

Stunt secrets

The Qantas 747 has a long and fantastic history—the ‘Queen of the skies’ connecting Australians stuck ‘down under’ with the rest of the world. Far-flung and exotic locations such as Bombay and Bahrain were suddenly accessible and, more importantly, affordable.

And it was apparent for the airline’s final 747-400ER flight (VH-OEJ), they had to do, in Owen’s words, ‘something really, really special’.

An idea had seeded itself into his mind and so the planning of the ‘roo began.

‘Everyone was so invested in making this work, everyone put their heart and soul into this process because it meant more than just flying, it really did,’ Owen says. ‘But honestly, I didn’t even have a clue where to start.

‘I went to our branding office and got images of our kangaroos but one thing that struck me from the start is that those logos are different to what we have on the aircraft—I took a bit of a risk in choosing that one, but thankfully it was approved.’

Using basic computer software, Owen traced the image and created waypoints in decimal form. Converting them to latitude and longitude, he ended up with about 150 waypoints. The key limitation was the tight turns needed for the tail, paws and around the head. ‘That was going to be a make or break as to whether we could actually do this,’ he says.

‘I ended up completing about five simulator sessions to see what radius of turn I could get. The first session clearly showed that at 20,000 feet in a clean configuration, this was not going to work—it was probably going to be twice the size of Tasmania!

‘From what I could work out, a five-mile radius had to be the target, with the flap limitation of 20,000 feet. Also, we were flying this aircraft to the US with cargo, so we had to work out what was practical in terms of fuel. We have never done one of these at max weight before. Wind effect would have made this unworkable as well.’

Enter Matt Bouttell, Qantas Manager Air Traffic Management and International Compliance, to help solve the problem.

“About a month out I received an email from our navigation department saying, very confidentially, they wanted to do some sky art and could I liaise with Air Traffic Control and get approval to do it and then in front of me was this screen print of a Qantas kangaroo!’ he says.

‘And of course, a thousand things went through my head, mainly that it was situated about 200 miles off the coast. It was a long way out and ADS-B [automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast] only works to a certain range. The other thing was that, even though there’s not much air traffic, there still are planes flying and that’s a very busy route through to the South Pacific and the US. And finally, just to complicate things more, it’s also military restricted airspace, so there was a raft of things we had to consider and sort out before we could get the go ahead.

‘We worked with Airservices, Defence and CASA to pull this off and everyone was so excited. But it was apparent early on that the ADS-B wouldn’t reach, so I asked Owen if he could rotate the ‘roo by 45 degrees. It was a firm “no” from him and I’m so glad we didn’t! The next step was to try and move it as close to the coast as possible and within as much military airspace as we could, so we didn’t affect air traffic in Sydney too much.’

Achieving the impossible

On the aircraft’s retirement day, Owen’s focus was getting through his checklist. Many of the 747s IT components are from the 1970s and 80s, meaning the waypoints couldn’t be uploaded automatically, so he did this manually. Then the actual ‘Roo sequence took an extra 90 minutes of flying time.

‘We needed to keep it as standard as possible—so I used full automatics and manual selected modes, where you manually select a heading with the autopilot and then control the angle of bank,’ Owen says. ‘I set it up at a normal bank of 25 degrees as everything had to be as standard as possible. The risks were the weight and, while it’s acceptable to take flap at those altitudes, you just don’t normally do that. Reverting to hand flying would have greatly raised the risk profile.

‘I created the waypoints and inputted them into the computer which drew a very nice-looking route. Then the problem is the automatic flight director system which has to follow those waypoints. And there are various limitations with that system. With a heavy aircraft, you can get behind the drag curve and that’s not a good place to be.

‘We started off at 25,000 feet and flew the back of the ‘roo’s foot higher and then descended so we could fly the tail at 19,000 feet with the flap configuration. We then flew that for the head and the paws and climbed up again for the fuel saving.

‘For the really wide arcs I could use the lateral navigation mode and it flew really beautifully, but for the tighter turns I used heading select mode which just holds a constant angle of bank and allowed a little bit of artistic licence to manage wind effects.

‘There was a little bit of westerly wind so, a bit like sailing, I could go upwind to tighten the corner and bring it back around.’

Back at the Qantas Integrated Operations Centre (IOC), Matt Bouttell was wondering whether the design would actually work, with the aircraft so heavy and at maximum fuel. He had his hopes up and fingers crossed—tightly.

‘Once the aircraft was at Wollongong, I started to breathe a bit but then they started the sky art part and that’s when I became really, really nervous,’ he says.

The aircraft had headed east over the Pacific Ocean before turning northwest, with a U-turn above Taree on the NSW mid-north coast to start on the tail.

‘This was confidential, and no one knew what was happening, not even Qantas staff,’ Matt adds.

‘The IOC was a pretty somber place [for the retirement flight] as you can imagine, so I made sure the IOC manager had the 747’s progress all on the big screens so staff could watch it live. You could see there was a bit of confusion when the 747 did the U-turn at Taree but as soon as they realised what was happening they were just all blown away. To say this was a massive achievement is an understatement.’

Owen concedes he only knew that the QF7474 crew had achieved the impossible after the flight had ended.

‘After landing in Los Angeles my phone had an absolute meltdown, I had over 100 messages,’ he says. ‘It made the news all over the world, more than 200,000 people watched us do the event live and it just captured people’s imaginations at a time when we all really needed something to boost morale.’

Farewell, ‘Queen of the skies’

Owen admits that when QF7474’s retirement day dawned on July 22, emotions were high, especially in the hangar.

‘It was particularly hard-hitting seeing the engineers who had defined their lives working on this aircraft, that really pulled at the heart strings,’ he says.

‘That’s when it really sank in, just seeing people everywhere in anticipation of the departure. It was so touching to see the water cannon, to see hundreds of people at Shep’s Mound [plane spotter’s lookout] and on the other side of the old tower—that’s when it all got real.

‘The flyover over Sydney was so heartfelt, and ATC couldn’t do enough for us. You could feel this shared love for this aircraft and what it meant to us and to Australia and the fact that this was it, this was actually it’s retirement, it’s swan song, it was really going.’

So, could Qantas have managed this stunt if the pandemic had not occurred?

‘It’s hard to answer that question,’ Owen says. ‘We already had big plans for the retirement flights but you just have to admit that this probably was enabled because of COVID. I just think the timing was right.’

“It’s been our pleasure to guide you through the skies safely and taking the #Queenoftheskies✈️through our airspace over the last decades.”🔊Listen to our air traffic controllers bidding farewell to the final @Qantas B747 flight departing Australia #747Farewell pic.twitter.com/LGTEwpnVV5

— AirservicesAustralia (@AirservicesNews) July 23, 2020

I was awe inspired by the creativity and uniqueness of a fitting, massive tribute to the closing chapter of the 747’s era of service to the Flying Kangaroo. The fair well signature flight embodied the sentiments of so many travellers lifelong memories of one of the worlds greatest air journeys across the globe aboard a QANTAS 747. A fitting tribute to a giant achievement in aviation and sky art that must surely be found in the Guinness Book of Records.

I can only hope a tribute wall poster will become available to hang in place on my office wall.