By Patricia Green

The truth that dares not speak its name in airline travel is that the polite, well-groomed and urbane person serving your food and drinks, usually with a smile, is not there for your entertainment, but your survival.

Should the unlikely happen, and you are seated and conscious afterward, you will depend on that person’s knowledge, leadership and teamwork for the final, most important phase of your interrupted journey.

Cabin crew are responsible for passenger lives and must be prepared for any scenario that may happen during a flight. Most ab-initio cabin crew training courses take six weeks and thereafter they undergo a short recurrent program each year to test their knowledge in safety and emergency procedures.

Training traditionally is through a mix of classroom instruction, aircraft visits and scenarios practised on cabin devices to simulate door and slide operation, evacuation of aircraft on land and water and fighting fires. Airlines are increasingly cost conscious and want to save time and money, while still providing their cabin crew with effective and efficient training. Virtual reality and augmented reality are already used for flight crew, ground crew and engineering training, and it is a natural progression to introduce elements of these into cabin crew training.

Virtual reality offers an interactive 3D e-learning experience with realistic visual and aural scenarios. It can take place in any room-size space or become completely portable with a headset linked to a smart phone or tablet. Specific skills can be learnt safely in a virtual world, without the person being endangered in real life. As anyone who has experienced it will confirm, virtual reality creates a visceral and emotional response that in all probability enhances recall and learning.

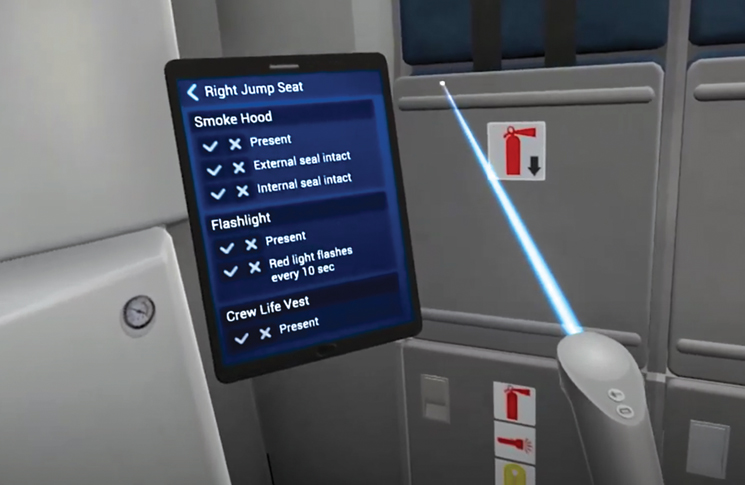

The trainee is immediately immersed into the experience and can participate in aircraft familiarisation and interact with virtual equipment in the galley or cabin. Virgin Atlantic implemented this in its cabin crew training for the Boeing 787 to help the cabin crew with spatial awareness. Door and slide operation can be practised effectively as many times as needed in a safe environment; this allows the trainee to consciously learn by doing, where traditional methods do not allow the time for this. Peer pressure to perform procedures perfectly first time can be an added stress during training, but virtual reality training would negate that.

Virtual reality offers an interactive 3D e-learning experience with realistic visual and aural scenarios.

Service procedures can be rehearsed prior to a flight, allowing the trainee to ‘operate’ as a crew member without the need for aircraft visits and multiple familiarisation flights, saving time and money for the airline. The trainee can play out a number of scenarios without needing individual trainer-to-trainee instruction and learn at their own pace. Scenarios could include emergency evacuation, medical emergency, dealing with an unruly passenger, performing a security check on the aircraft or putting out an oven fire—without risk.

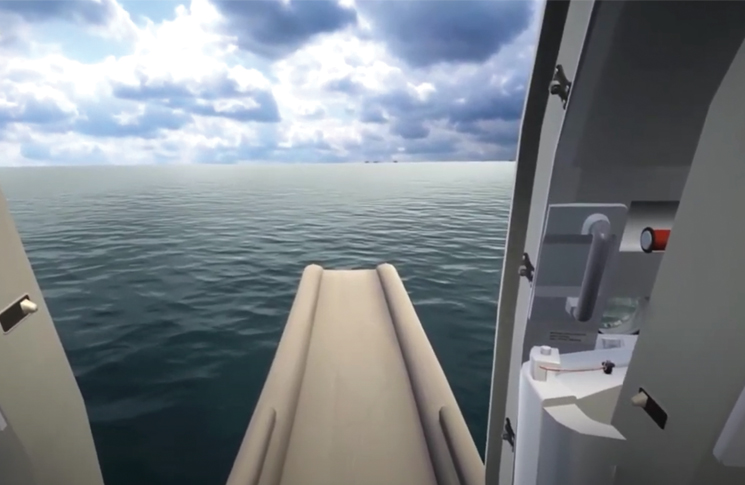

Virtual slide training with a ‘dark room’ set up outside a fuselage door trainer can further the experience, allowing the trainee to ‘see’ conditions outside the aircraft (fire, smoke, water) and any obstacles to an evacuation.

The benefit to the airlines is considerable as it reduces the need for a physical simulator cabin and provides a cheaper method of training. There is less aircraft downtime for familiarisation purposes and less use of ground support and the aircraft’s auxiliary power unit.

Training can be remote if necessary, without the need for a physical simulator and the constraints of traditional educational models. The trainees learn by doing—the training time using virtual reality is much less and it is a very efficient method of training. The traditional approach focuses on the individual being trained, one person at a time, whereas this approach allows for up to 12 trainees to be trained at a time. However, operating crew are still required to demonstrate proficiency in the operation and use of safety and emergency equipment, as well as demonstrating other competencies in accordance with non-technical skills and human factors.

The training outcome can be recorded and repeated as necessary and integrated with computer-based training records and learning management systems. The trainee’s performance can be scored and the feedback is instant.

A study of virtual reality in cabin crew training by the University of Udine in Italy looked at the design and evaluation of mobile and immersive cabin crew training. The study discovered cabin crew became more competent, resilient and had a better internal locus of control, and the training was shown to be an effective way of learning and improved knowledge transfer as well as preventing errors. Research showed that it reduced the failure rate on real-world simulators by 50 per cent.

The University of Exeter in the UK also studied the potential use of virtual reality in cabin crew training. The trainees described feeling ‘present’ in the aircraft familiarisation, suffering no feeling of sickness and finding ‘gamification’ made the experience enjoyable. Some crew members reported it was fun, engaging and less stressful than traditional training and found they had improved concentration. In turn, learning the location of equipment and onboard processes sped up considerably. Potential flaws included possible motion sickness and loss of sense of self, which could affect the learning experience.

Will virtual reality become the future for cabin crew training? At present, there is room for both, with virtual reality being complementary to traditional training methods. Airlines including Qatar Airways, American Airlines and Philippine Airlines are using it in recurrent training. Lufthansa trains 18,500 cabin crew every year using VR techniques in their recurrent and inflight service training.

Use of virtual reality in cabin crew training will no doubt continue to grow in certain applications but needs to be subject to scrutiny by aviation authorities to ascertain its place within the industry. My conclusion is that it can augment as an educational experience, speed up training time and may improve knowledge; however, it should not be a substitute for training on a real aircraft, although it could potentially replace some elements of traditional cabin crew training.