Much of what you read in articles about flying safely revolve around aircraft crashes. We most assuredly must learn the lessons those who have had accidents can teach us, but thousands of flights take place every day that do not end in tragedy. What can we learn from the habits of highly effective pilots?

Although ‘I didn’t crash’ is a low bar to set for safety, we can also learn much from the pilots who, day in and day out, do things right as pilot-in-command—practices and attitudes that seem to support mishap-free flying to develop a set of habits for highly successful aviators. Instead of thinking about what pilots have done wrong, let’s look at how pilots go about doing things right.

Highly effective pilots watch what the weather is doing every day

Watch the weather

I was in the right seat of a piston twin. My host was flying us back to Brisbane after I’d taught a weekend pilot safety event in Cowra. We knew that afternoon thunderstorms were likely, so we left early in the day. Although they had not yet formed, the pattern over the previous couple of days showed we might get past in time, but we could angle east and land at Coffs Harbour if we needed. As it turned out that’s exactly what we had to do, the decision made easy because we had been watching the weather for days.

In my experience, highly effective pilots watch what the weather is doing every day, not just when they are going to fly. They have a curiosity about what’s happening, not just where they live, but around the entire country.

A pilot who lives in Melbourne will have an idea of when that cyclone is going to make landfall in Queensland and whether the drought is likely to break near Adelaide. Even though they are not going to fly that far, or fly that day at all, they like having an awareness of how weather patterns are forming and moving on a continental scale.

More locally, effective pilots glance at the sky every chance they get, evaluating the clouds and the wind. They like to be able to guess when a front will come through or when the fog will burn off. They look at METARs and TAFs. They look out the window and quiz themselves on cloud heights and visibilities, and whether what they see describes a turbulent atmosphere or a smooth flight.

In short, highly effective pilots maintain good situational awareness of the weather as it exists where they are and how it is expected to develop and move. On the day they fly, whether across great distances or just around the circuit, they already have a good idea what the weather will be. It’s just a matter of filling in specific details for a flight instead of trying to develop a weather picture from nothing. You can do things right by watching the weather.

Have a plan

A friend offered me a joy flight in his Tiger Moth during one of my visits to Queensland. He briefed me that his intercom system was not great, and we did have that somewhat incompatible accent thing going between us—my failing, not his. In his frustration to communicate with me in the front cockpit as we climbed, he pulled himself forward by the cockpit coaming to shout turn directions in my ear … accidently turning off the Tiger’s fuselage-mounted magneto switches in the process. The pilot handled the resulting engine stoppage expertly, but a little pre-flight communication by both of us would have prevented the whole scenario. Before we went back up, we briefed in detail about when he would hand control over the me and when I’d give it back to him, and the specific route and manoeuvres we’d fly. The second hop was less exciting, but it was much more enjoyable.

Flying is about freedom, and pilots must be flexible to changes that come up during a flight. But effective pilots have at least a basic plan worked out ahead of time. This reduces the need for having to make many decisions in flight and provides a benchmark for making decisions if changes occur. ‘Plan your flight and fly your plan.’ That’s another way you can do things right.

Plan and monitor fuel

I’ve been on several aerial tours in Beech and Cessna aeroplanes with my Australian friends. We’ve been to Longreach, Winton, Birdsville, Uluru and White Cliffs; Armidale, Cowra, Narromine and Canberra; and Flinders Island, Clare Valley and Wilpena Pound, all from jumping off points at Noosa, Archerfield, Moorabbin and Lillydale.

With full cabin loads, each trip has been an exercise in fuel loading, strategy and in-flight monitoring, always keeping options available at these sometimes very remote locations. I joke that everywhere in Australia is three hours’ flight from everywhere else. On each leg of each flight, the fuel load was always balanced and we always had a sizable fuel reserve on landing. Even when over extremely uninhabitable terrain, not once were we ever concerned about having enough fuel.

The US National Transportation Safety Board reports that as much as 90 per cent of all engine failures that lead to an accident report are the result of fuel starvation (having fuel on board but that fuel not being sent to the engine) or fuel exhaustion (running completely out of fuel). If you’re concerned about engine failures, focus on fuel level confirmation before flight and monitoring once in the air. You can prevent virtually all engine failures by doing things right.

Know your limitations

I was the guest of a friend who was taking me to the Avalon air show. I was staying in Melbourne at the time, and another friend was going to pick me up at Moorabbin, then hop me across the bay to Avalon. The temptation was great for us both to let me see Melbourne from the air before arriving at the famous air show. But the surface winds were strong and gusty, so my friend decided—and I would never pressure anyone otherwise—to forgo the flight and let me ride in by car with my host.

An excellent pilot is always evaluating a planned flight against their experience and recency and the capability of the aeroplane. Sometimes this means deciding not to make a flight even if the perceived benefits of that flight are great. At other times you might alter the circumstances, if possible, to eliminate the threat. To be effective at making these types of decision, you must be truthfully aware of your limitations and act to remain within them. Yes, we all need to stretch our skills and expand our personal flight envelope at times. But going beyond the edges of your limitations is something that should be done under controlled circumstances with an experienced flight instructor—not alone without a backup or with passengers. If you’re aware of your current limitations, it’s easy to do the right thing. And that brings us to …

Use checklists and standard operating procedures

I think I’ve flown right-seat with nine different Australian pilots, including two I’ve flown with in the United States. Every time I got into the aeroplane with a pilot I’ve never flown with before, I was confident that despite the extreme distance between where they learnt to fly and where I learnt and teach, we would have a common frame of reference for how to fly the aeroplane and address the type-specific demands of the particular aircraft in which we flew. That’s because we use a common set of checklists and standard operating procedures (SOPs).

Aeroplanes can be fairly simple or very complicated. Regardless, they are complex mechanical devices operating in a unique and often unforgiving environment. Over time pilots, engineers and designers have developed specific sequences of action to best prepare for and accomplish flight operations. Many of these are documented on aeroplane checklists.

Think of a checklist as having an expert in the cockpit providing you advice on the best and most efficient way to fly the aircraft. To confirm you didn’t miss a critical task in normal operation or for advice in an unusual or emergency situation that is outside your personal experience, consult with the experts—use the checklist.

SOPs go beyond the way you perform tasks. They describe when you perform those tasks. For example, you have a before landing checklist and a landing checklist, each to ensure you perform the myriad tasks necessary for a safe arrival. An SOP for arrival in the circuit may include some additional advice on power settings, but more importantly tells you when it’s appropriate to perform the checklist items. In other words, an SOP might call for completing the before landing checklist prior to entering the circuit and to confirm those items are done before turning onto final approach.

Checklists and SOPs complement one another and together give you guidance to improve safety and reduce cockpit workload. Using checklists and SOPs are very much doing the right thing.

You can prevent virtually all engine failures by doing things right

Train beyond minimums

I’ve been fortunate to make all these Australian pilot friends and have these many wonderful flying adventures Down Under because I was there as a speaker at pilot training events. Every other year the Australian Beechcraft Society holds a three-day training and social event, the Beechcraft pilot proficiency program. The Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) and the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) often play a part, as well as vendors and other speakers. The pilots attend classroom training and complete a syllabus-focused training flight with a type-specific standardised instructor. They’ve invited me to teach the classroom session six times now and with luck I’ll be back in 2021.

The minimum standards for pilot training and currency are designed to create pilots who are capable and safe. However, truly effective pilots use these standards not as an end goal, but as the starting point to being even more proficient and safe. Many pilots feel that experience alone is enough, but experience results only from learning about what actually happens to you.

On the other hand, training is learning from the experiences of others. Training also supports correlation, so you can apply the lessons you’ve learnt with your experience to respond correctly in case an unforeseen scenario unfolds. Continuing to add experience through regular training is the right thing to do, so you’re as ready as possible if you encounter a situation in flight you’ve never seen before.

Learn from every flight

As each pilot landed at Cowra for last year’s event, I tried to greet as many as possible to introduce myself and learn more about them. As is usually the case with pilots, it didn’t take much effort to get them talking about where they had flown from and the experiences they had had flying from their homes to the training site. In addition to learning more about the pilots, I was prompting them to think about how the flight went and how they performed—a self-debrief that only takes a few minutes but can solidify any lessons learnt from the recent experience.

Every flight is a learning experience. There are always things we did quite well and maybe a few we could have done better. If you take a moment to think about the specifics, maybe even write down a few notes—’I’d do this differently next time’, ‘I tried this and it worked great’—you will better remember your experiences and become a better pilot. That’s doing the right thing!

Rightly so, much of what you read and see about aviation safety revolves around a discussion of an accident. That’s learning from the experiences of others—a vital component of safe flying. Because of that emphasis, however, it’s easy to forget that thousands of flights occur around the globe every day in the highest safety flying an aircraft allows. The pilots of these aeroplanes were effective at doing things right. As you fly, then, focus on doing the right thing.

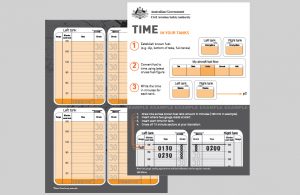

Time in your tanks Available at shop.casa.gov.au

Flight planning kit Available at shop.casa.gov.au

Designed to assist low-hour VFR pilots with good flight planning habits. Includes a handbook outlining eight stages of a flight, flight planning notepad, personal minimums card, time in your tanks card and more.

Great story including Beechcraft Society meeting at Cowra.

When and where is the next meeting?

Regards

David

Old Beech pilot

Great article..nice to read something positive.

Check lists don’t have a memory. They can’t forget!!

Great article.