By Kreisha Ballantyne

How do you tell clouds apart and, more importantly, which ones are dangerous?

For pilots, clouds are more than a natural wonder—they also need to be understood.

According to the ATSB, 101 occurrences of VFR pilots inadvertently flying into IMC in Australian airspace were reported from 2009 to 2019.

In 2006 Flight Safety Australia published a memorable article, ‘178 Seconds to Live’, which explored the dangers of VFR in IMC. Years later, the publication revisited the article to discover very little had changed: on average, Australian air traffic controllers are called upon every 10 days to assist a pilot in deteriorating weather.

While VFR pilots are taught to avoid—and sometimes even fear—cloud, IFR pilots, while permitted to enter cloud, can still become quickly unstuck. Certain cloud types are potentially deadly, as Lieutenant Colonel William Henry Rankin discovered in 1959. The only known person to survive a fall from the top of a cumulonimbus thunderstorm cloud, Rankin was flying an F-8 Crusader jet fighter over a cumulonimbus cloud when the engine failed. Although not wearing a pressure suit, he ejected into the −50 °C air, suffering immediate frostbite. After 10 minutes, Rankin was still aloft, carried by updrafts and getting hit by hailstones. When conditions calmed, he descended into a forest. It had been 40 minutes since he had ejected.

While the chances of having an engine failure atop a storm cloud are exceptionally rare, an understanding of clouds is vital to pilots, whether VFR or IFR.

What are clouds?

Simplistically, clouds are made of water vapour, a gas present in the air. Clouds appear when there is too much water vapour for the air to hold.

Rising air holds clouds up. When air rises, it cools. Cold air can’t hold as much water vapour as warm air so, as the air cools, it becomes saturated and the water vapour in it condenses, turning from a gas to a liquid, much like condensation on a cold window. When the water vapour turns to a liquid in the sky, it forms tiny water droplets which cling to particles of dust—it is this group of droplets suspended in the air that becomes visible as clouds.

The person who named the clouds

The man accredited with providing the names of the clouds we still use today was English chemist Luke Howard, known as the ‘father of meteorology’.

Howard’s cloud-naming scheme was detailed and exact—he based his findings on the shape, colour and height of clouds and detailed them using Latin descriptions. After naming the clouds, he focused on the effect of the weather on the clouds, positing the idea that clouds are good visible indicators of the changes and instability in the atmosphere.

His naming scheme made it easier for modern day meteorologists to determine the different types of clouds. Moreover, included in his scheme of cloud naming is a system of shorthand notation symbols, used in cloud observations universally.

The classification of clouds

Luke Howard classified clouds into three basic shapes.

Cumulus—means heaps. These clouds are usually in masses or heaps with tops looking like cauliflowers with flat bottoms. They look like bunched up puffy cotton in the air.

Stratus—means layer. These layers of clouds look like blankets and mattresses in the sky. These clouds are distinguished for their wideness.

Cirrus—means curl. Cirrus clouds look like curly and wispy hair up in the sky. They are thin and often look like a child’s hair.

Nimbus—means rain. This cloud doesn’t have any specific shape and is often in combination with other clouds. Clouds that will cause precipitation will have the name nimbus on them like cumulonimbus or nimbostratus.

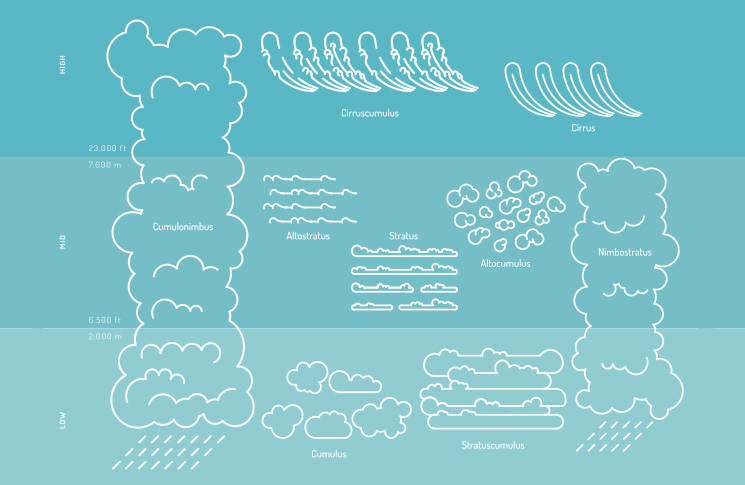

There are three layers in the atmosphere and, within the four types of clouds, there are 12 major cloud types which emerged from the cloud naming system Howard developed.

Cumulus family: heaps, puffy, cotton-like

- Cumulus (fair-weather)

- Swelling cumulus

- Cumulus congestus (towering cumulus)

Stratus family: layers, blankets

- Stratus

- Altostratus

- Cirrostratus

Raining cloud family

- Cirrus

- Nimbostratus

- Cumulonimbus

Heaps and layered

- Stratocumulus

- Altocumulus

- Cirrocumulus

A closer look

Stratus clouds tend to form when a large mass of air rises at more or less the same speed, to cover a large part of the sky. They are generally flat and offer poor visibility.

Cumulus clouds form when parcels of air are rising while air is sinking nearby. While the bottoms of cumulus clouds typically are flat, the tops can rise like castles in the sky. You’ll usually see breaks between the clouds. While generally harmless, Cu can change and develop very quickly, becoming the thunderstorm cloud known as towering cumulus. These are the clouds to be avoided.

Clouds higher than 20,000 feet are called cirrus or have names beginning with cirro. Since they’re so high, they are made mostly of ice crystals, although scientists have found super-cooled water drops. Cirrus clouds have wisps of snow falling from them that quickly evaporate. Solid sheets of these high clouds are called cirrostratus clouds, while those with lumps are cirrocumulus clouds. Although these clouds don’t directly affect most general aviation pilots, they often offer clues to the weather in the next two or three days—they could be the leading edge of the clouds created by an approaching storm.

Clouds between roughly 6500 feet up to 20,000 feet AGL have names beginning with alto. When you see middle-level clouds begin to replace high-level clouds, you should suspect that lower clouds and precipitation are on the way.

Clouds below 6000 feet don’t have a prefix indicating their height. If they are lumpy, they are cumulus clouds of various kinds. If they are flat, they are stratus clouds or have strato or stratus in their name, such as nimbostratus.

To tell stratocumulus, altocumulus and cirrocumulus clouds apart, extend your arm pointing at the lumps in the clouds. If your little finger covers a lump, the clouds are cirrocumulus. If your thumb roughly covers one of the lumps, the clouds are altocumulus. If your fist is needed to cover a lump, you’re looking at stratocumulus clouds.

Towering cumulus: a glider’s perspective

If you want to truly understand clouds, go flying with a glider pilot.

‘From a pilot’s point of view, the bigger and taller a cloud is from base to top, the more dangerous it is,’ European glider pilot Max Walter says. ‘The big ones, sometimes passing 40,000 feet, can make flight through it uncomfortable, if not deadly.

‘If any part of a cumulus cloud is at your altitude or higher, stay away. If there are other Cu in the area, plan to avoid them and always keep your eye open for an escape route, heading either where there are fewer clouds or descending below the bases. Sometimes the best solution is to turn back toward where you came from.

‘If there are lots of Cu in the area and many have tops that are higher than, say, 15,000 feet, think highly unstable. As a VFR pilot, never fly above a cumulus cloud or even try to climb above them unless you have an oxygen equipped aircraft that can climb strongly into the flight levels. Cumulus can often out climb general aviation aircraft and the tops can be higher than most GA aircraft can reach.

‘It’s often turbulent under Cu so if possible don’t fly underneath them and always avoid flying under the anvil head, even if you’re in the clear, because of the potential for extreme turbulence and even hail.

‘Also, if you have the choice, fly upwind of cumulus because the worst turbulence is usually on the downwind side. Have a healthy respect, avoid the big and fast growing ones, have an alternate plan and stay alert.

Beware of the ice!

Clouds that hold the potential for icing include cirrus, cumulonimbus, cumulus, stratus (particularly lake-effect stratus clouds), orographic and wave clouds. Whether or not a cloud will produce icing is dependent on the outside temperature and the amount of moisture within the cloud.

Fronts also pose the risk of icing. Along a warm front, warm air mixes with cooler air to form stratus clouds conducive to icing. Along a cold front, the colder air mass lifts the warmer air, creating cumulus clouds conducive to icing. If you have to fly through a front, it’s important to remember to take the shortest route possible, so as to minimise exposure to potential icing conditions.

Ice fog is another icing hazard that can affect aircraft. It only occurs when temperatures are much below freezing (usually -25 degrees F or colder), causing moisture in the air to super freeze and form ice crystals. This condition usually happens in the early morning or at night and when there is a small temperature to dew point spread.

What to do when storm clouds abound

Avoidance

- Don’t land or take-off in the face of an approaching cloud build-up. A sudden gust front or low level turbulence could cause loss of control

- Avoid the anvil of a large cumulonimbus by at least 20 nm

- Regard as extremely hazardous any towering Cu with tops around 35,000 feet. Even if you can see through to the other side of the storm, do not attempt to fly under it.

Don’t get trapped

- Always have a way out—left, right or behind you—and make sure it remains available

- Descend early—be well below the cloud bases long before you reach them

- Avoid the temptation to climb above rising Cu tops—the options after that will be very limited if the weather does not pan out as you wish

- Watch for rain that doesn’t reach the ground (virga) and stay away

- Continually assess flight visibility with ground references—when it falls below the minimum for VFR flight, activate the ‘way out’ and stick with it. Two hours on the ground can see a storm come and go, after which the flying conditions will probably be much better.

CASA’s Weather to fly DVD is available at shop.casa.gov.au

Comments are closed.