By Alwyn Brice

Is there a failsafe way to instil the subject of safety into your workforce?

Over the last two decades of editing industry publications dedicated to the aviation sector, and more specifically to what happens on the ramp, I’ve read many thousands of words penned by safety professionals about the intriguing topic of ramp safety. It’s a subject that never sleeps but, as yet, has no simple answer.

If there was a silver bullet (and you’ll excuse the clumsy metaphor—after all, we are talking safety here), then it would have been discharged long ago.

One of the key tasks of any safety officer is ensuring the welfare of their workforce. Not only that, it’s also vital that the employees work sensibly and understand the nature of risk and what should be done to avoid anything that could be deemed dangerous in their day-to-day activities. The first few days a new employee spends on the ramp are typically overshadowed by awe: the proximity of real, live aircraft, the complexity of tasks that comprise the turnaround and the (seemingly) casual familiarity exhibited by those driving vehicles around the apron. There’s much to assimilate and an awful lot to learn, even in a task as basic as loading or unloading baggage.

Of course, today the new worker is trained (often within a classroom environment) before being allowed out to where the action takes place and the buddy system—teaming

up with a responsible co-worker—usually reinforces that training. (There’s a danger here, though, of the recruit picking up bad habits from his mentor, but I’ll come back to that possibility later).

Part and parcel of any good training course involves the flagging of the inherent threats that inhabit the ramp. Years ago I had a desk diary, one of those small thick pads that comprised a tear-off leaf for every day of the year. Each leaf was inscribed with an epithet or some sort of adage but the one that still lives with me after 40-odd years, read: ‘The only way to feel safe is never to feel secure.’ If only this simple sentence could somehow be hardwired into the brain of every ramp worker, wouldn’t life be a lot better—that is, safer?

Given it’s likely that handling companies would run foul of WH&S in any attempt to perform the above concept, we are left hunting around for other methods to make sure all that accumulated safety experience doesn’t just evaporate once the new staff member has been in the job a few weeks. Many and varied procedures have been adopted over the years, and here I am going to discuss three. I cannot say with hand on heart that all, or indeed any, of the following will be the answer to the safety prayer, but they ought to give food for thought.

Room with a view

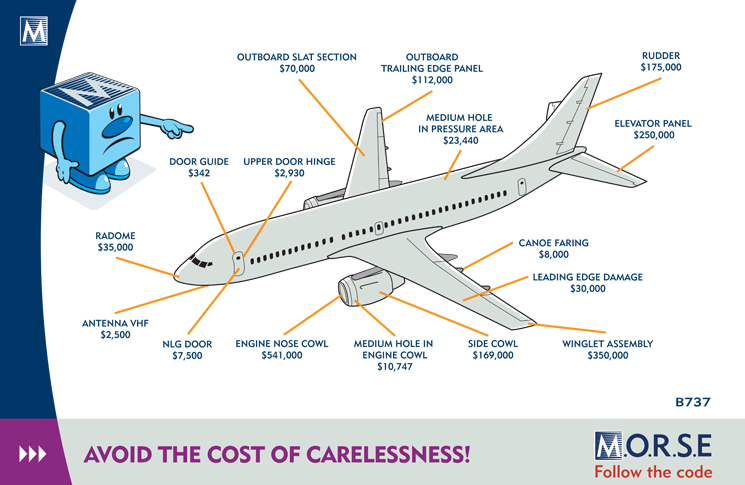

Having been around many airports over the years, I can say a common element is the ramp worker’s crew room. These vary according to location and tend to be practical rather than palatial. In one I came across some interesting artwork on the wall. Depicted in profile was a parked aircraft, the sort of thing that was familiar to all who used the facility. Lines had been drawn from various parts of the aircraft’s anatomy: the nosecone, engine nacelle and cargo hold doorframe, for example. Each of these lines terminated in a figure prefaced with the sterling sign.

The point being made was both obvious and immediate: strike the aircraft in such a location and that’s what it costs to put right. The message being put across was, I suppose, subliminal, and didn’t require any input on the part of team leader. The image served as a constant reminder that ground damage was no light matter—and the sums involved reinforced the need to work carefully around such expensive commodities.

A penny for your thoughts

While I don’t have much experience working on the ramp, I have been able to drive ground support equipment. One of the most daunting tasks is that performed by the de-icing operator. It’s one thing to sit in a cab on a boom and squirt water over a dummy wing on a test day but quite another to manoeuvre a bulky truck around an aircraft in the half light of dawn in poor, typically freezing weather conditions. You have to admire these workers, whose job is always carried out in the worst climatic conditions imaginable.

US company IDS is well known in the realm of de-icing, having made a name for itself some years back by challenging the status quo of service delivery. Instead of charging the airline by the gallon of glycol used during the operation, the company came up with a schedule of fixed de-icing tariffs, which varied according to aircraft type. It was thus incumbent on the provider to use just the right amount of fluid in each de-icing event. This could only be achieved by thorough and ongoing training—which was the method IDS adopted in the off season.

The IDS operators, in some respects, can consider themselves as a part of a special club—and each carries a coin. This is an IDS monetary unit and effectively reinforces the team spirit. If one member pulls it out of their pocket, then any other teammate who might be in conversation with them is obliged to do the same. The ‘coin challenge’ is a way to remind employees to make safety the top priority. It is (I believe) a unique strategy within the handling sector. IDS has been using the ‘safety coin’ concept for more than 10 years, according to Pat Brown, the company’s VPO Sales, Marketing and Customer Relations.

‘The idea was originally brought to IDS from someone who came from the US Air Force where, in my understanding, it has been used throughout the US military for over a century,’ he says. ‘This is now a very big part of IDS’s exceptional safety culture and record. I would add that at any time you are “challenged” by anyone from IDS, around 98 per cent of our employees would have their coin with them.’ Every year, different safety coins are distributed which, through an annual contest, are designed by an IDS employee.

Multilingual situations

Language is vital when it comes to correct communication. However, the reality is that many airports have staff who have come from all around the world. Therefore, getting the safety message across is no easy matter, especially where the audience’s native tongue is not that of the trainer or ramp leader. One simple expedient I have come across in Asia is a laminated card that is light on text but big on pictorial representations. If the images or cartoons are of sufficient quality, then words can be superfluous. The main safety issues can be highlighted on the card, which should be small enough to be carried in a pocket of the employee’s uniform. It’s not hi-tech nor expensive and doesn’t require huge amounts of study. Sometimes, the best solution is simplicity.

The examples mentioned here are merely solutions that I have come across—there are sure to be others in operation out there. However, the real point to be made here is that positive attempts to underline the safety message can be made—and a tangential approach could prove to be the optimal answer. As these approaches show, it’s all a matter of what works best for you.

Comments are closed.