Behind what appeared to be an open-and-shut case of human error was a set trap of human and technical factors that was ready to close, but did not, by the narrowest of margins.

Numbers tell this story as eloquently as words ever could. Here are a few of them.

- 4 Aircraft lined up on taxiway Charlie at San Francisco International Airport

- 13 The vertical distance in feet (4 metres) between Air Canada flight 759’s lowest point and the fin of the second aircraft

- 60 The approximate minimum altitude in feet (18 metres) of flight 759 above San Francisco International Airport taxiway Charlie before it went around

- 19 The length of time in hours the captain of flight 759 had been on duty

- 140 The number of passengers and crew on flight 759

-

1000+ The number of people who could have been killed or injured if the aircraft had collided. It would have been the world’s worst air disaster

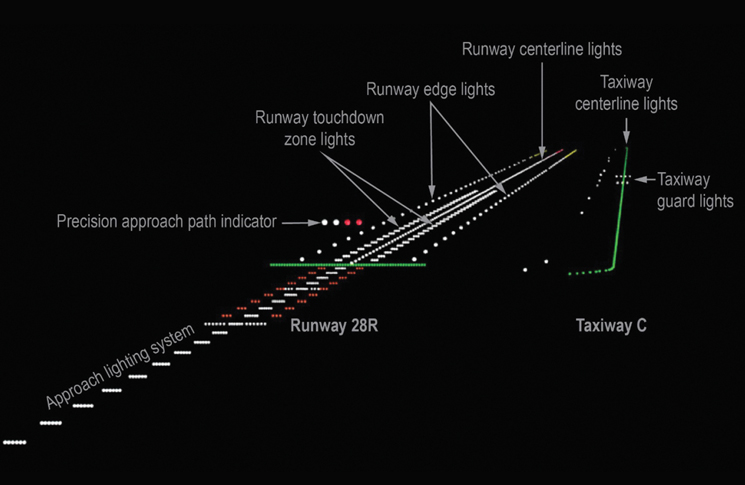

In the final few minutes of 7 July 2017, Air Canada flight 759, an Airbus A320, was on final approach to what its crew thought was runway 28R at San Francisco International Airport. They were instead lined up with the parallel taxiway Charlie, an illusion made possible by the closure of runway 28L that night.

Taxiway Charlie held a Boeing 787, an Airbus A340, another Boeing 787, and a Boeing 737, waiting for clearance to take off from runway 28R. Flight 759 descended to 100 feet above ground level (AGL) and overflew the first Boeing 787. By then the crew of flight 759 had begun a go-around, but its momentum caused the aircraft to briefly keep descending. Its lowest height was about 60 feet as it overflew the second aeroplane on the taxiway before starting to climb. Radio traffic, which had been lively with disbelieving utterances from the pilot of one of the waiting aircraft and a belated go-around instruction from ATC, subsided, and flight 759 landed without incident on its second approach.

Creative Commons 2.0

Long day’s journey into fright

Flight 759 had pushed back at Lester B. Pearson International Airport, Toronto, at 9.25 pm local time, 30 minutes late. The flight data recorder (FDR) data showed the throttles were advanced to take-off power setting about 9.58 pm with the autopilot engaged shortly after wheels up and remaining engaged until just before final approach.

The flight was uneventful except for an area of thunderstorms, which the crew navigated around at about 9.45 pm San Francisco time or 12.45 am Toronto time. The captain and first officer told the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) they had started to feel tired just after clearing the storms.

Nearing San Francisco, at 11.21 pm local time (2.21 am Toronto time), the first officer obtained the automatic terminal information service data tagged as information Quebec. It included the closure of runway 28L, as did a few coded letters on page 8 of the 27-page package of NOTAMS in the flight briefing. Information Quebec was not spoken, as in smaller or older aircraft, but displayed on the A320’s aircraft communications addressing and reporting system display.

The late-night arrival to San Francisco used Air Canada’s FMS Bridge visual approach, based on the published Quiet Bridge approach. Like all the company’s visual approaches, it required back-up lateral guidance from the instrument landing system (ILS) to confirm the aircraft was lined up with the intended runway. But by a quirk whose significance would come to be appreciated the next day, FMS Bridge was the only approach in Air Canada’s Airbus A320 database that required manually entering the ILS frequency into the aeroplane’s flight management computer (FMC). Lateral guidance is particularly important at San Francisco, because like many large airports (including Sydney), it has several parallel runways, 28 Right and 28 Left, in this case.)

It was the first officer’s task as pilot monitoring to enter ILS frequency into the radio/navigation page on the multifunction control and display unit (MCDU). This he did not do. The first officer told the NTSB that he ‘must have missed’ the MCDU radio/navigation page.

The two pilots held an approach briefing, during which, in accordance with Air Canada’s procedures, they listed and discussed any threats associated with the approach.

The captain told the NTSB they had discussed the night landing, the busy airspace and how ‘it was getting late’, meaning they would need to ‘keep an eye on each other’. Later analysis found the briefing missed two things. The captain and the first officer were not able to remember whether they discussed the closure of San Francisco’s runway 28L. And the captain did not verify the ILS frequency had been entered. Neither pilot noticed ILS frequency was not shown on the primary flight displays (PFD) and the FDR later confirmed that the ILS frequency had not been tuned.

As the aircraft approached the airport, the first officer was looking down, programming the missed approach altitude and heading and setting the runway heading.

The captain lined up for what he thought was runway 28R, having interpreted the lights of the real runway 28R as 28L. In fact, he was lining up with taxiway Charlie. However, the captain felt some unease at the pattern of lights appearing ahead of him because he asked the first officer to contact the controller to confirm that the runway was clear. The first officer looked up and seeing taxiway Charlie ahead, presumed that the aircraft was aligned with runway 28R due, in part, to his expectation that any competent captain would align with the landing runway. He said, ‘Just want to confirm, this is Air Canada seven five nine, we see some lights on the runway there, across the runway. Can you confirm we’re cleared to land?’ The aircraft was at 300 feet.

The controller confirmed that 28R was clear, but by now aircraft landing lights were clearly visible on the ‘runway’. (Although the Air Canada crew reported they never saw any aircraft.) At 100 feet, having already overflown the first aircraft on taxiway Charlie the first officer called for a go-around at the same time as the captain began one.

Who, what and how?

In The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error, Professor Sidney Dekker makes the point that the informal ‘bad apple’ theory of error, in which flawed and culpable humans stuff up a perfectly good system, contains the highly dubious assumption that the system itself is inherently safe. The NTSB investigation took a similarly thorough view, seeking to isolate reasons why the pilots (a 20,000-hour captain and 10,000-hour first officer) had done what they had.

Expectation and confirmation biases, which are a normal part of human thinking, had played a role the NTSB said. ‘Both biases occur as part of basic information processing, and a person may not be actively aware of such biases at the perceptual level,’ it found, adding similar thinking patterns had been involved in several previous cases of wrong-surface landing. The wing tip and flashing beacon lights of the waiting aircraft could have resembled runway lighting by enough to let these biases take their course, the NTSB reported.

Fatigue emerged as a contributing factor. The incident had happened shortly before 3 am by the flight crew’s normal body clock time. This was well into the period when the flight crew would normally have been asleep and at the start of a time known to sleep specialists as the window of circadian low. During this period, even well-rested people become fatigued and subject to the errors and reductions in performance that fatigue brings.

At the time of the incident, the captain (who had been on reserve) had been awake for more than 19 hours, and the first officer had been awake for more than 12 hours. ‘Thus, the captain and the first officer were fatigued during the incident flight,’ the NTSB concluded.

The San Francisco Tower controller, although better rested, was the only one on duty and several crew on the waiting aircraft pointed out how busy he had been at the time of the incident.

Another crew who had landed at San Francisco shortly before the incident remembered difficulty in lining up with the correct runway. The first officer of Delta Airlines flight 521 said, ‘the construction lights were so bright we could not determine the location of the inboard runway, 28L. So, I initially thought the construction was on a taxiway and we might be lined up on runway 28L and the taxiway on the right could be runway 28R.’

Satellite navigation-based systems that issued spoken confirmations of which runway an aircraft was lined up on were available but were not installed on the incident aircraft.

Several NTSB members added personal statements to the report. Board member Earl F. Weener said, ‘As a long-time pilot and flight instructor, I understand that mistakes are inevitable for even the best aviators. Thus, it is critical that safety systems are installed with redundancy and multiple layers which work effectively to mitigate, correct or prevent these errors.’

Vice Chairman Bruce Landsberg said, ‘it’s almost a certainty this crew will never make such a mistake again and my hope is that they will continue to fly to the normal end of their careers.’

Landsberg was more critical of NOTAMS, and their role in in the incident. He said they put ‘an impossibly heavy burden on individual pilots, crews and dispatchers to sort through literally dozens of irrelevant items to find the critical or merely important ones. When one is invariably missed, and a violation or incident occurs, the pilot is blamed for not finding the needle in the haystack!’

Weener noted that neither the incident crew nor the controller of the crews of the other aircraft reported the incident immediately. The Air Canada crew ‘was apparently unclear on the meaning of ASAP’, and the controller did not report it until the end of his shift. The crews of the departing aircraft ‘took no immediate action prompting an intervention and evaluation of the Air Canada crew’.

Because reporting was delayed, the CVRs of all aircraft involved continued recording, and soon overwrote the record of the incident. Nothing was gained from them.

Landsberg said there was more to be gained from being introspective rather than judgmental. ‘We should reward all aviation personnel and celebrate when someone self-confesses a mistake and learns from it. More importantly, the system learns from it and can take steps to eliminate event precursors. This is a key factor in the decades-long decline in commercial aviation’s accident rate. Fortunately, we’ll get another chance to put some fixes in place to make a highly improbable event even less likely to reoccur.’

Comments are closed.