by Kreisha Ballantyne

In the late 19th century, a Polish ophthalmologist named L. L. Zamenhof created a universal second language called Esperanto. His goal was to foster communication and international understanding by developing an easy and flexible second language.

Esperanto is spoken by around two million people worldwide and is surprisingly popular in China. Like many native English speakers, it’s been a personal goal of mine to learn a second language, something at which I have never succeeded (despite growing up in Wales).

Or so I thought.

I’ve come to realise that aviation is its own language, and in its way, it’s a kind of Esperanto: although primarily the international language of aviation is English, for many, including native English speakers, aviation is a second language, containing new words, formal procedures, specific pronunciations and a multitude of abbreviations. It only takes one flight with a non-pilot to realise how much acronym we speak: TAF, QNH, VOR, EFB, ERSA, ATC, OCTA, etc.

If aviation is a language, then it has two levels of comprehension: VFR and IFR. As a VFR pilot, the language and procedures of instrument flying have always intrigued me: LSALT, sector entry, missed approach, RNAV, holding pattern, etc. Being of a curious nature, and with a permanently optimistic ideal of achieving an instrument rating myself one day, I decided to spend some time in the right-hand seat with instrument-rated pilots. It was during this experience that I realised that every VFR pilot would benefit enormously from speaking and understanding a bit of IFR.

Using IFR in flight planning

One of the most obvious distinctions between IFR and VFR is in the flight planning stage, with some flying schools offering different planning sheets and EFBs offering two tier levels of subscription for IFR and VFR.

Flying VFR doesn’t mean you can’t prepare a detailed flight plan for every flight, filing it with a NAIPS flight notification, rather than as SARTIME-only. This facilitates entry to controlled airspace, flight following and rapid assistance if things go wrong. I have lost count of the number of air traffic controllers who have told me in interviews that filing a flight plan, regardless of flight rules, improves flight safety tenfold.

When preparing for a flight, consider the published lowest safe altitudes when planning cruising levels. You can fly visually, perfectly safely, clear of terrain below the LSALT almost everywhere, but being above the LSALT adds an extra dimension of protection to your flight. It’s possible to use your EFB to calculate LSALT, even when there isn’t a published one.

When planning a long trip, consider using a methodology similar to the IFR for alternates: for VFR flight, the weather is the principal issue, although navigation aids and lighting can matter too, and especially at night. For the weather, IFR pilots consider the cloud base, visibility and crosswind for landing. For a VFR pilot, much the same logic can be applied: is the cloud base high enough to permit a safe departure, VFR flight to the destination, and then a circuit on arrival? For example, if a coastal aerodrome elevation is 98 feet AMSL, the circuit will be flown at 1100 feet and an overflight, 500 feet above, may well be necessary to sight the windsock and establish circuit direction.

While it’s legal to fly VFR clear of cloud below 3000 feet AMSL in Class G airspace, that may not be safe if there are surrounding hills—so an experienced VFR pilot might adopt an alternate minimum of 2500 AGL. If a cloud base less than this is forecast, the flight doesn’t proceed unless there is an alternate aerodrome with much better weather conditions en route, or not too far away. Similarly with visibility, the legal VMC criteria, in the same situation, of 5 km (think of it as five runway lengths, or just being able to see the runway from a three-mile final), may not be safe in some circumstances and locations, so many experienced VFR pilots make plans for an alternate if the visibility is forecast to fall below 8 km.

Remember, the purpose of alternate planning is to ensure that you have a sensible, workable back-up plan, and the fuel to support it, if things don’t turn out as you might have preferred.

Using IFR weather planning

Approaching the weather with as much detailed information as possible is a favourable approach regardless of the flight rules under which you fly.

Being aware of the multiple weather resources available will assist you in flight planning. The BOM Knowledge Centre offers a staggering amount of user-friendly information on weather related topics such as regional hazards, hazardous phenomena and information on the GAF and GPWT. Additionally, BOM offers an area specific weather package that includes the latest MSLP chart, satellite image, currently valid graphical area forecasts, local TAF and METAR/SPECI, Area QNH, Australian SIGMETs (except volcanic ash), local weather observations, public weather forecast and four-day prognosis charts.

Knowing how to read TAF, TTF, METAR (SPECI and routine), GAF, GPWT, AIRMET and SIGMET, can significantly increase the safe outcome of your flight. Using detailed weather information to your advantage, especially when conditions are changing may mean the difference between completing the flight or not.

Understanding how to apply the ‘dew point spread x 400’ rule to calculate the cloud base when cumuliform clouds are present is an old trick taught to IFR pilots. Take the dew point from the AWIS or Area Briefing, subtract it from the dry bulb temperature and multiply the difference by 400 to calculate the base of the cloud, for example, if the temperature is 21, and dewpoint 14, (21-14) x 400 = 2800 feet, which is the likely base of cumulus cloud.

Airframe icing, on its own, shouldn’t be a problem for VFR flights (except in some rare circumstances) but knowledge of the freezing level can aid in understanding the weather environment. Higher temperatures detract from climb performance in naturally aspirated piston engine aircraft, so if the freezing level is way up in the flight levels, don’t expect stellar climb performance in such an aircraft at maximum weight for a climb to 9500 feet. If the freezing levels are very low, consider the likelihood of frost, or icy pavements. Realistically, very low freezing levels in Australia (say, below 5000 feet) are often accompanied by low cloud and should be an indicator to study the forecast carefully, even for VFR flight.

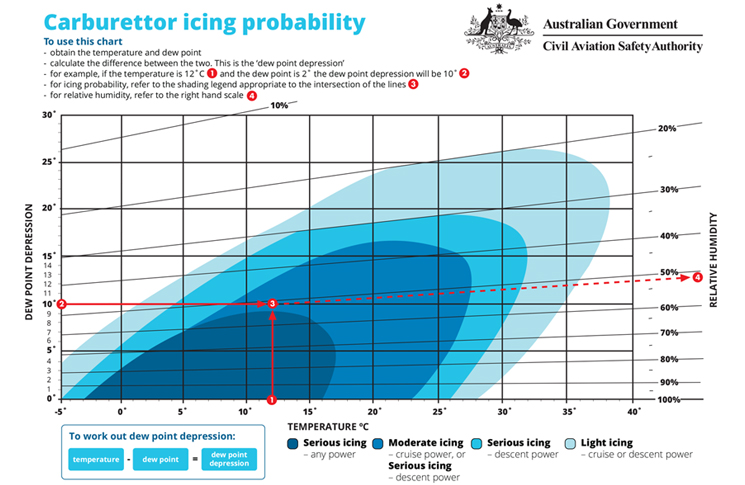

Carburettor icing can be an issue for VFR aircraft every bit as easily as IFR aircraft. Carburettor icing conditions can easily arise when flying VFR, even away from the clouds. CASA offers an excellent carburettor icing probability chart which is an onboard must for all pilots flying carburettor-equipped aircraft (see resources).

Using IFR en route

Always understand and know how to use all the equipment you have on board, regardless of your flight rules: GPS, VOR, ADF and radio equipment. If you’re flying in a sophisticated aircraft, take the time to learn the advanced features (such as traffic monitoring, coupled autopilot, weather detection and synthetic vision). Study the manual so that you can recognise the functions and purpose of the approach capabilities, even if you don’t use them. Learn to use the GPS to the full extent of its functions, especially flight plan entry, proper use of direct-to, re-joining a planned course, understanding RAIM and integrity, integration with other cockpit displays such as PFD or MFD and database content and currency.

Conversely, if you’re flying an older aircraft with an ADF, it’s worth understanding it—you don’t have to be able to fly approaches, but knowing how to fly headings to maintain a constant ADF track, and the difference between bearings and radials, can be valuable.

Keeping your altimeter QNH current, whether flying locally or on long travel flights, is a tip I learnt from an experienced IFR pilot. When requesting Area QNH, inform ATC of your location and destination or intentions. Taking the time to learn how to use Flight Following properly on travel flights can make things much easier. When using Flight Following, don’t change frequencies, altitudes or tracks without advising ATC.

VFR pilots who routinely listen out on the area frequency are rewarded with useful information about nearby traffic and often enough, conditions ahead. It also means you can respond if ATC issue a hazard alert, particularly in relation to traffic that you have not yet sighted.

Learning how to give departure and position reports, especially if flying over water or through remote areas can help, especially when broadcasting in busy areas; however, make sure you make it clear in the broadcast that the flight is VFR.

When responding to an IFR aircraft that may be conflicting traffic, be clear about your position in relation to a waypoint that will be known to an IFR pilot. ‘Tracking back into the 11 downwind from Curlewis’ probably means nothing to an IFR pilot, but ‘10 miles south of Gunnedah, inbound, 3500’ is unmistakeable about your intentions. Inform the IFR traffic when entering the circuit and always in accordance with the recommended procedures for Class G aerodromes.

At your local airport, make an effort to become familiar with the instrument approach tracks. Then, when you hear an IFR pilot report ‘on the 23 RNAV, 7 miles’ or ‘in the holding pattern, 5200’ you’ll have a reasonable idea where to look. Bear in mind that an aircraft on instrument approach will be around 1000–1500 feet above its approach minimum at 5 miles, which will probably put it close to circuit height at that position and an almost certain conflict for a VFR aircraft on downwind.

When using Special VFR, it’s vital you’re across the applicable rules and be ready to speak up if the cloud or visibility worsens. Entering IMC when VFR is a potential death sentence, and still one of the major causes of aircraft accidents. When flying under Special VFR, the ensuing disaster will unfold even more quickly—there is no such thing as instrument visual flight! At a Class D control zone, expect your Special VFR clearance to be cancelled if an IFR aircraft arrives, or is ready for departure. In these circumstances, the safest course of action is usually just to land and wait for the IFR aircraft to clear the area.

In marginal VMC, knowing which way to turn if cloud or deteriorating visibility arises quickly will enable you to seek better visual conditions fast. If there is no possible ‘Plan B’, the weather is probably unsuitable for VFR flight.

Using VFR for safety

Finally, bear in mind that flying VFR does not mean unprofessional or less safe; indeed, it can be argued that the greater flexibility of VFR flight makes the need for pilot professionalism, expertise and skill even greater.

There are days when it is safer to fly VFR than IFR. When there are more than isolated thunderstorms, VFR sometimes works better, since the VFR pilot never enters cloud and is able to remain clear of the storms, associated rain, traffic, terrain and airspace restrictions visually. Checking the freezing levels can also significantly improve the chances of flying VFR on days when instrument pilots may stay on the ground. For example, when freezing levels are very low, it can be difficult to find an altitude above the LSALT and acceptable to ATC to cross the Melbourne control area under IFR: but under VFR, there will be other options.

A safe flight begins with a detailed plan, continues with a pilot’s ability to be flexible and able to adapt, and ends with everybody safe on the ground. Whether you’re VFR or IFR, proficiency in the language and rules of aviation will enhance the safety of your flight.

And, as they say in Esperanto: scio estas potenco—knowledge is power.

Resources

Bureau of Meteorology Knowledge Centre

CASA’s Carburettor icing probability chart

Online shop:

Monitor your risk of carby icing using this laminated A5 chart. Reverse side features a list of fast facts. Visit: shop.casa.gov.au and use code SP106.

Interesting article, somewhat long winded but there’s something for everyone. The only downside with today’s modern techno stuff available for the VFR driver is that it’s dangerous as in the amount of VFR drivers out there in IMC is very scary! I’ve seen too many times A/C flying in and out of cloud or pop out of cloud and they are meant to be visual at all times! Like everything mankind invents it gets abused!

interesting artical sort of, more like brush up on VFR procedures long winded definetly most VFR pilots should have a clear understanding of the contents of that artica,l their PPLtraining would have covered most that was written ! to me the artical is all about procedures for flight safety, which is good, but all of us should already have those procedures iimbedded in our brains , if not so, then yes, that artical would b very helpful to brush up on procedures ! the flight safety side that most pilots would benifet from including myself is learning from other pilots who have gotten into difficulty, ,and by good piloting or sheer luck have passed their story on. this is wot i see as flight safety, so it can b avoided in future flights.! Safe Flying

“For example, when freezing levels are very low, it can be difficult to find an altitude above the LSALT and acceptable to ATC to cross the Melbourne control area under IFR: but under VFR, there will be other options.“

I don’t understand this one – can someone explain better please?

VFR means you can fly around a CTZ ( if clearance is not avail) and remain clear of clouds and storms etc below LSALT therefor mitigating the icing risks and still be safe/legal.

Practice makes perfect. Repetition is the key to safety and articles like this are great reinforcement of existing knowledge

Excellent article re VFR Ops and especially applicable to NGT VFR. There is nothing visual about NGT VFR with a high overcast / moonless night in Australian inland.

Also VFR is in someway a dispensation to allow flight below LSALT hence extra awareness helps keep one’s number of landings equal to number of take-offs!

NGT VFR – forget a horizon for outback operations on moonless high overcast flying Eg Charters Towers to Longreach.

Keeping current for NGT VFR – a Hood and Safety Pilot friends can be very worthwhile so the above flight can be hand flown with confidence.

Adding Instrument Flight Practice to BFR’s also maintains confidence. Aircraft well equipped and maintained makes for higher safety even if my Instrument Rating is not current hence NGT VFR is necessary and no problem in such an aircraft.

Reliance on VISUAL senses only – (for me) needs currency hence practice under the hood with Safety Pilot looking out! Hope this may help someone new to VFR at night.

I agree wholeheartedly with the comments regarding the fact that sometimes it is safer to fly VFR than IFR. I recently conducted a flight from Bankstown to Sunshine Coast in exactly this situation – low freezing levels and mid level cloud meant that the IFR option was untenable. However, a coastal VFR flight below an overcast all the way was safe, simple and stress free.

Indeed, on the return trip a few days later, VFR to Ballina then IFR for middle stage of the flight to Taree followed by VFR for last third of the flight was the way to go, due to weather factors.

Plan carefully and choose the most appropriate flight rules for the flight (or sector).

Great article. Thanks for the mini briefing.

I thought it was a great article and appropriate for new pilots in training (and relatively speaking, I’m one of them with 140h PIC on gliders with cross country and 1h solo on power). Nothing substitutes for the Flight Instructor, but as you say, “knowledge is power” with repeated advice from experienced pilots to drum in the message.

What is interesting though is technology in the cockpit. Knowing how it all works, esp GPS with linked Autopilot etc is right in IFR territory, so even though you are a VFR pilot, you are somewhat forced to understand IFR to really appreciate the tools on the flight deck. These tools are so good.. you get a lot of confidence and think you are – invincible! And likely the reason VFR pilots are flying in and out of clouds. The issue with young or low time pilots with technology is they are impatient and feel they are above the rules. The rules were made by old pilots with no feel for the benefit of new technology. Whilst this is naïve, there are two things here… firstly, technology is moving very rapidly to make it very safe to fly in almost all conditions (think autonomous passenger flying drones) and secondly, regulations to verify and check the viability of new technology to ensure it’s safe and allow rule changes to match. So a VFR cross-country endorsement may someday be approved with the use of IFR style equipment and autopilot with moving maps (and a handheld or separate backup IFR style device) only rather than a 6 pack dials, watch and a physical VTC/WAC.

At the end of the day, your article is timely as more and more new pilots are inadvertently studying IFR (especially since they can practice easily using Microsoft’s new Flight Simulator).