US journalist Harry Reasoner was renowned for his way with words. Two paragraphs he wrote on helicopters in 1973 have hovered for many years on the internet.

‘The thing is, helicopters are different from airplanes,’ Reasoner wrote in Approach magazine. ‘An airplane by its nature wants to fly and, if not interfered with too strongly by unusual events or by a deliberately incompetent pilot, it will fly. A helicopter does not want to fly. It is maintained in the air by a variety of forces and controls working in opposition to each other, and if there is any disturbance in the delicate balance, the helicopter stops flying, immediately and disastrously. There is no such thing as a gliding helicopter.’

‘This is why a helicopter pilot is so different a being from an airplane pilot, and why in general, airplane pilots are open, clear-eyed, buoyant extroverts, and helicopter pilots are brooders, introspective anticipators of trouble. They know if anything bad has not happened, it is about to.’

Leaving aside the pedantic question of whether autorotation is a glide or a controlled fall, Reasoner was clearly on to something: his words have been gleefully quoted by proponents and detractors of helicopters for nearly half a century. But are there really unique helicopter human factors? And if so, what are they?

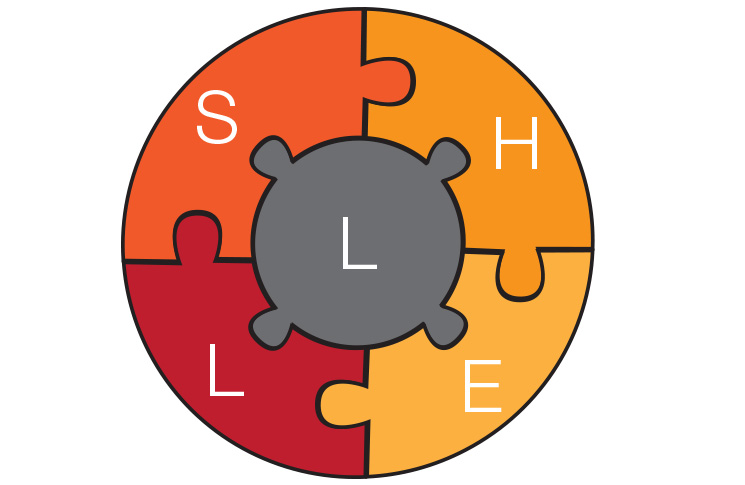

Human factors is a broad term that can mean anything from aeromedicine to how people inside and even outside of the cockpit interact. ICAO uses the SHEL (software, hardware, environment and liveware) model to represent the various components of the human factors’ pantheon. This can be expanded to SCHELL—software, culture, hardware, environment, liveware: individual human, and liveware: between humans.

Software is the rules, procedures, checklists, written documents, operating manuals and standard operating procedures (SOPs) that support flying operations. Some of this is regulated whilst some is a preferred or best way of achieving the flying. Helicopter operations are regulated by CASA and helicopter companies are required to have operating manuals etc. Are there any real fundamental differences between helicopter and fixed wing software issues? There shouldn’t be.

Culture includes norms, customs, practices, conventions and habits that occur beyond SOPs, and regulation. A working definition is ‘the way we do things round here’. It is often what occurs to get the job done when under perceived pressure. Culture may be specific to the actual flying but could also be what you experience in the crew room. A poor culture seen in the crew room or socially could indicate a poor flying culture. Poor culture will often develop with substandard leadership and supervision, and can lead to deviation from software including violations. A culture not conducive to safe flying operations may be imported from other groups that the pilot operates with. The helicopter mustering industry has seen poor culture in the past. In this case, the issues may also be structural: pilots are often away from supervision for long periods of time working with people who have a different culture. Similar cultural interaction may be found in fixed wing firebombing operations or remote fixed wing charter operations. The young mustering helicopter pilot may have to be more aware of the influence of culture than their peer fixed wing charter pilot. This is difficult because culture, by definition, is something that surrounds you 24/7. Its continuous presence can make it hard to notice.

Hardware is the physical elements of the system such as the helicopter itself, the tactile interfaces, displays, or cockpit layout. The hardware may be a simple helicopter such as an R22 with direct mechanical controls or it could be a large helicopter with hydraulic boosted controls, a stability system and an autopilot. Large helicopter flight control system complexity can exceed that found on airliners. The displays could be simple conventional round dials or large flat panel displays. In external load helicopters the critical engine instruments may be replicated below the side window to allow the pilot to monitor the load without having to look away to check engine performance. Night vision devices (NVD) and forward-looking infrared (FLIR) are widely used by helicopters in rescue and emergency services. NVDs in the civilian aircraft industry are much more prevalent in helicopters than fixed wing aircraft.

Environment consists of the internal cockpit with temperature, humidity, noise and vibration as well as the external cockpit with things like weather, sun, moon, terrain and landing areas. Helicopters operate at lower altitudes and not all cockpits are airconditioned, so heat may be an issue. Helicopters can operate with the doors off for better visibility and this can mean that wind chill can become a factor. Helicopters are often noisy and experience more vibrations that a fixed wing aircraft. The advantage of a helicopter is its ability to hover and land vertically and this means that they operate close to terrain and often in unsurveyed landing areas. The low-level environment and unprepared vertical landing areas are unique to helicopter flight compared to fixed wing aircraft. These unprepared landing areas are often not surveyed, may contain obstacles and can, without warning, have reduced visibility from a brown out of blown dust—or a white-out of snow.

Liveware: individual human considers the limitations of the individual such as fatigue, ability or stressors. Many of the aeromedical disorientation and illusions experienced in fixed wing are applicable to helicopters. One that is specific to helicopters is flicker vertigo where light coming through the rotor blades creates a strobe effect. This strobe effect can cause disorientation, vertigo and nausea and in the 1950s was investigated in several helicopter accidents. In extreme cases flicker vertigo can induce seizures in susceptible people. Looking away from the light source or repositioning the helicopter so the sun isn’t shining through the blades and into the cockpit may be required. The use of NVD hardware introduces another set of aeromedical limitations including increased fatigue, unique optical illusions and degraded visual environments.

Liveware: between humans considers the interaction between people and is often covered by crew resource management (CRM). It also includes humans external to the aircraft including ATC or support staff. At first consideration this does not sound overly different from fixed wing aircraft. However, not many fixed wing aircraft rely on non-pilot crew to provide clearance from obstacles in an unprepared landing zone. Mustering helicopters interact with musterers on the ground and firebombing helicopters may be coordinated from other aircraft or firefighters on the ground. In the low-level helicopter environment, there may be a unique set of liveware interaction required between individuals to complete the task safely.

Culture, crossover and compensation

The critical point to remember with the SCHELL model is that the liveware individual, the human, resides at the centre (see Figure 1) and the interaction between the other components is also important. Culture permeates all the other elements. We can see that there is some crossover between elements such as NVD hardware and the aeromedical issues they introduce to the individual. The system needs to be balanced, with deficiencies in one area covered by strengths in another. Improving the liveware individual by better training may be able to compensate for deficient hardware issues. An example is specific training to rapidly recognise and respond to rotor speed decay in small helicopters where this happens quickly. Improving company flying culture and SOP software may allow more inexperienced individuals (liveware) to operate safely without close supervision.

Figure 1: SCHELL model diagram

So, there are some unique helicopter human factors, but the strongest difference is the environment—close to the ground in uncontrolled, unsurveyed landing areas relying on non-pilot crew and ground support staff to provide key safety information. Although helicopters operate slower when close to terrain there is still little time for a pilot to recover from a human factors’ breakdown.

The ability to land almost anywhere and quickly gives the helicopter pilot a major advantage when it comes to dealing with emergencies or threats: as the Helicopter Association International says, you can land and live. Many helicopter emergencies quickly become non-emergencies because the helicopter can rapidly be put on the ground if faced with a system malfunction, running into bad weather or coming up a bit short on fuel. In this respect, a helicopter is closer to a wheeled vehicle than an aeroplane. The ATSB, together with CASA and AHIA, recently published Don’t push it, land it—When it’s not right in flight which explains that making an early decision to land your helicopter during the onset of an abnormal situation will reduce the likelihood of an accident.

However, this advantage is often ignored as the helicopter pilot tries to get home with a malfunction or after dark or pressing on into bad weather. Does the company have written guidance on land-out procedures (software)? Do the senior pilots always get airborne in bad weather to have a look (culture)? Is the helicopter rated for night VFR (hardware)? Does the terrain being flown over allow for a ground vehicle rescue (environment)? Will the maintainers be annoyed having to drive out to fix the helicopter (liveware: between)? Is the pilot tired after a long hot day and not realise how close to dark it is (liveware: individual)?

Be ready for a precautionary landing by carrying some water, food, a mosquito net or a sleeping bag, at the very least. This shows you are prepared physically and mentally to land. The helicopter’s unique ability to fly very low, land and take-off vertically nearly anywhere is also the greatest risk if there are poor human factors. An EC135 accident in November 2015 showed the stark difference between landing and continuing on in poor weather and fading light. The pilot had made a precautionary landing due to bad weather then decided to take off again in poor weather and reducing light. The aircraft struck terrain, killing everyone on board.

This discussion is not meant to be a definitive list but more to provoke you to think about the human factors in your helicopter operation. There are some differences in human factors for helicopters with arguably the most significant being related to its unique ability to operate at very low level and land almost anywhere—you just need to ensure that poor human factors don’t prevent you from making the decision to land and live.

Comments are closed.