The mission description in the accident investigation is delivered in the sterile prose so typical of the military … except for the last word:

The mishap crew’s mission was to fly the mishap aircraft to Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona—commonly referred to as the ‘Boneyard’.

The ‘Boneyard’: a colloquialism for a desert storage facility in Tucson Arizona where many surplus aircraft go to rest. As with a lot of metaphorical nomenclature wedged into the sterile prose of mil-spec language the term is as colourful as it is widely used. Of course, no-one tasked to fly an aircraft to the boneyard would have ever thought the colourful and widespread use of ‘boneyard’ would ever mean they were flying to their own boneyard. At least not until 2 May 2018. The aircraft was a 1965 model WC-130H Hercules—most recently used as a specialised weather-recon plane. It rolled off the assembly line when its last crew weren’t even a half-twinkle in their parent’s eyes: 53 years later it rolled itself into a fireball off the end of Savannah’s International runway.

Reading this accident report made me remember the early days of my flying career and something that really bugged me. Here we were, highly trained military aviators groomed to fly highly demanding missions with highly specialised military helicopters—except we weren’t. Where once we flew multi-ship, low-level airmobile operations we now sat on our proverbials waiting for a callout. Where once we flew regular night and day winching operations, we now sat around flicking through study guides and flight manuals wondering if this week we’d actually get to pull pitch. Where once our tasking had been comprehensive and varied, we now pretended by ‘wargaming’ with mud maps and seconded white boards.

The age of aeromedical (AME) standby had arrived. This meant for large scale exercises our squadron would fly to all corners of Australia and then sit around for weeks on an end waiting for a call to respond. Because the exercises were generally well planned the calls rarely came. This meant—literally—weeks on end with pretty much zero flight time. Young pilots and crewies sitting around for long periods are not a recipe for good morale, hence the ‘it really bugged me’ comment. There are, after all, only so many games of Risk one can play before one feels like poking one’s eye out with the sharp corner of one’s cup canteen.

Looking back while looking in; that is, looking in at this C130 accident makes me realise something. Instead of being bugged I should have been worried—really worried. The time on the ground wasn’t just boring, it was dangerous. It was a vigilance-sucking fade from mastery to mediocrity. It was the reverse of the famous incremental boiling of the frog. We, along with our operational and technical savviness, were being cooled degree by degree into a frozen mediocrity.

At the time we of course complained bitterly. Why couldn’t we do more continuation flying? Why couldn’t we maintain AME standby while flying around? Why weren’t we doing air mobile operations anymore? Surely HQ weren’t happy about the huge waste of multi-million-dollar helicopters just sitting around?

Looking back, I realise there was probably a good a dose of whinging as there was concern for more flight hours. I could definitely have been more circumspect about the very real pressures that were on command at that time. Nonetheless the point remains: the slow fade is a dangerous fade.

The C-130 accident very much encapsulates this message. Take for example this pre-crash comment from maintainers (captured by the C130’s CVR) as they attempted to rectify a low rpm problem on the number 1 engine:

’99 per cent rpm is good enough … it’s going to the boneyard anyway …’

99 per cent is good enough. Except it wasn’t 99 per cent and it wasn’t good enough. The number 1 engine was only providing 96.8 per cent. The maintenance crew could never have known this because they had chosen to ‘eyeball’ the aircraft gauges rather than, as procedures required, connect a precision tachometer. The specialised C130 required a specialised adaptor plug but the maintainers mistakenly thought the instrument kit had no such adapter. Therefore ‘near enough was good enough’ and the mark 1 eyeball, not a precisely calibrated instrument, was used for fault finding. Without the tachometer to read data directly from the engines, and with the aggregate errors of near-ancient engine gauges, the maintainers drew a seriously wrong conclusion about the health of the engine.

The near-enough/good-enough mentality had been around for a long time. It came with the lack of flight hours. As core skills begin to degrade so did core attitudes. I felt it myself on those long months of AME standby. There’s a kind of mental mode that develops, a mode of mental mediocrity. It’s a ground-hog day kind of thing: get up, pre-flight, read a bit, do some ground training, check the weather, have some chow, read a bit more, do some more ground training, have lunch, read some more, check the weather (oh man I wish a call would come in), play Risk with the lads, dominate the world, dinner, go to bed, get up, do it again, and again … Sure, like bread crumbs falling off somebody else’s well-stocked table, the occasional flight would fall our way but it wasn’t enough to pierce that vigilance-sapping mental mode.

I should probably say at this point we weren’t sitting around with lower lips wobbling under the weight of self-indulgent self-pity. We knew complacency was an issue. We talked about it. We discussed it. We warned each other about it. We did whatever we could to revise and refresh our knowledge. But deep down we knew. We knew if our vigilance was a cutting edge that cutting edge was as dull as a cheap knife. You could see it. The first pre-flight of the exercise was careful and thorough: pre-flight number 51 several notches less so. The first weather briefing involved crews with a lively, engaged sparkle in their eye: number 51 saw the sparkle turn opaque. The first operational reports were carefully thought out and constructed; the last were short and perfunctory. This is what a mental mode of mediocrity looks like in everyday practice for flying-crews turned into long-term standby-crews.

Except for the fireball, what happened to us happened to this C130 crew. Over many months aircraft and aircraft hours were being reduced. Pilots were flying less, and maintainers were maintaining less. This meant, in turn, crew mastery dulled further and further. The evidence is scattered throughout the report:

- ‘There was a certain degree of apathy and low morale within the unit.’

- ‘Aircraft availability, affected crew proficiency and forced the unit to seek other means to keep aircrew current and qualified.’

- ‘During the course of the investigation, several recurring factors emerged with regard to health and low morale.’

- ‘Many of the airmen interviewed commented on the low morale and overall health of the Wing.’

- ‘Wing members repeatedly stated how the low morale was affecting their operations and causing manpower shortfalls because many people left the unit.’

The RPM problem had been noted by both pilots and maintainers several times but each time the nature of the problem had been under-stated and ultimately ignored. On the morning of 2 May 2018, the problem would not be ignored any longer. As the crew began the take-off roll the revs of the troubled number 1 engine began to fluctuate in what should have been an immediately alarming matter. Neither pilot noticed. Eight seconds prior to rotation, the revs on number 1 decayed well below flight range and still neither pilot noticed.

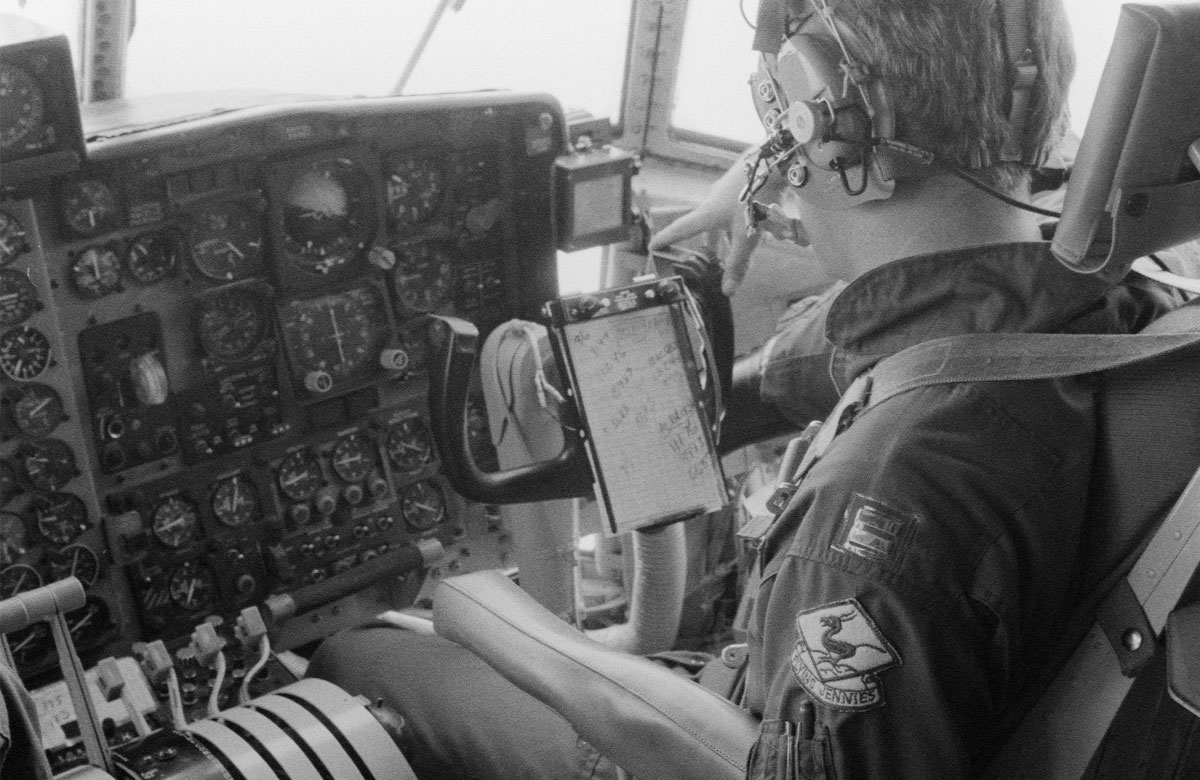

Any pilot who hasn’t flown for a while notices a certain sluggishness in one’s scan of instruments. Everything takes just that little bit longer to find and read. Another symptom of mental mediocrity. The photo of the cockpit and the complex array of instruments (see below) of the four engine Hercules shows how a sluggish instrument scan would have been exacerbated by the sheer number of instruments and how the number 1 revs would have been missed.

The scan was the only thing that was sluggish. With only three of four engines providing useful thrust the aircraft struggled to get to flying speed. This meant less aerodynamic efficiency on the control surfaces. With slower airspeed the pilot had to fight to keep the aircraft straight as it neared take-off. Just before take-off the tug of war between pilot and low-speed aerodynamics was nearly lost as the C130 veered left towards the grass just prior to toiling its way into the air. With degraded airspeed and control, the crew finally noticed the reason: the number 1 engine.

For a highly proficient crew, well-practiced and recent, a mental mode of mastery would have made this emergency a relatively simple one. A quick and ordered procedure from the checklist would have seen the ‘Take-off Continued After Engine Failure’, the ‘Engine Shutdown’ and the ‘After Take-off checklist’ complete and the aircraft landed safely. Instead the pilot on the controls, without the cognitive resources provisioned by a mastery mentality, brutalised the left rudder pedal. The 53-year-old airframe twisted its flight path into an ugly skid as its speed dropped below three-engine controllable. Without the mental capacity to run the checklists and ‘clean up’ the aircraft, the flaps remained at 50 per cent, while the aircraft tried to climb futilely into the sky.

The airspeed was all wrong. The angle of attack was all wrong and a deadly left-wing stall developed. The stall turned into a nose drop to 52 degrees and the nose drop turned into a barrel roll onto a Georgia State Highway. The nine people on board the aircraft were all killed. WC-130H, T/N 65-0968 never made it to the boneyard because it created its own.

The final stages of the tragic flight are captured here on video

The name ‘boneyard’ is significant. When I visited Tucson, I felt a wistful sadness as I stared at the silhouettes backdropped by the setting sun. Aircraft rest at the boneyard with engines inhibited and systems functionless. What were once powerful aircraft are just bones at a graveyard: all form, no function. Life is gone. Movement is gone. What remains is stillness. And yet, because of the preserving effects of the desert air, many aircraft look the same as on-line aircraft—as if they can do what mission-ready aircraft can do. But deep down I and anyone watching know these aircraft cannot do what on-line aircraft do.

I see a metaphorical parallel between the mental modes of mastery and mediocrity: they may look the same but once the demands of an emergency take hold it becomes evident one has cognitive life while the other only has form. The fact is a mental mode dulled from mastery to mediocrity isn’t any more mission-ready than an inert aircraft at the boneyard. T/N 65-0968 warns us that for those who continue to believe there are ‘other means’ apart from appropriately distributed flight hours ‘to keep aircrew current and qualified’ ‘boneyard’ may well be about to take on the same immanent meaning as it did on the 2 May 2018.

The pernicious slide “from mastery to mediocrity”. Such an incisive article. Should be required reading for senior Defence people.

“It was a vigilance-sucking fade from mastery to mediocrity. It was the reverse of the famous incremental boiling of the frog. We, along with our operational and technical savviness, were being cooled degree by degree into a frozen mediocrity.”

“From mastery to mediocrity” described in several scary ways.

Incisive indeed, Rob.

On point, Parky. Couldn’t agree more. Many countries struggle with this problem though not all of them have a safe ‘boneyard’.

Sharing widely. Kaypius.