The pilot was known as extremely capable and meticulous, and ‘an officer and gentleman of truly great distinction’. At age 41, he was chief test pilot of the US Army Air Corps and had flown just under 60 different types.

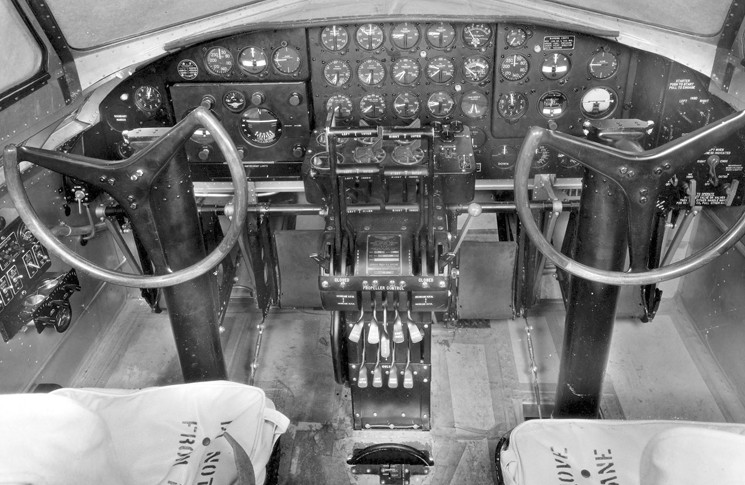

Today’s flight was of a four-engine prototype bomber built to address the Air Corps’ latest contract for an anti-shippng aircraft. On board was the manufacturer’s test pilot and three observers.

Whether it was Major Ployer ‘Pete’ Hill or co-pilot Donald L. Putt who failed to disengage the Boeing Model 299’s gust locks is not clear. One report tells of how Boeing test pilot Leslie R. Tower, presumably realising the error, tried to unlock them on take-off but could not reach them from his observer’s seat.

Immediately after take-off, the 299 suddenly pitched up, climbed to about 200 feet, stalled, crashed, and caught on fire. Putt and two observers were able to escape with injuries. Hill and Tower were rescued from the burning flight deck in an extraordinary act of heroism by an Air Corps pilot, First Lieutenant Robert K. Giovannoli, but they died from their burns.

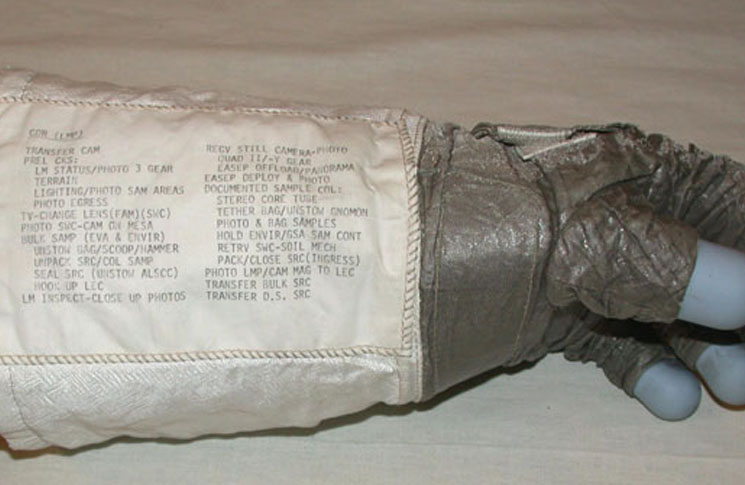

The cause was apparent in the wreckage. By January 1936 Flight International was reporting, ‘It is said that the crash was caused through the pilots taking off with locked controls.’ Boeing, which had been favourite to provide the new bomber design lost the contract with the crash of 299, but it persisted with the design and the Air Corps eventually adopted it as the B-17. More than 12,500 B-17s were made during World War II, where they were flown by young men mostly plucked from civilian life with no previous aviation experience. The military trained them to fly giant bombers in formation using a series of checklists.

‘The major function of the checklist is to ensure that the crew will properly configure the plane for flight, and maintain this level of quality throughout the flight and in every flight,’ wrote NASA human factors researcher Asaf Dagani, (with Earl Wiener) in his ground-breaking 1990 study Human Factors of Flight-Deck Checklists: The Normal Checklist.

Dagani noted checklist use was particularly important in take-off, approach and landing. ‘Although these segments comprise only 27 per cent of average flight duration, they account for 76.3 per cent of hull-loss accidents,’ he said.

Dagani listed eight objectives for using checklists. He said checklists:

- aid the pilot in recalling the process of configuring the plane

- provide a standard foundation for verifying aircraft configuration that will defeat any reduction in the flight crew’s psychological and physical condition

- provide convenient sequences for motor movements and eye fixations along the cockpit panels

- provide a sequential framework to meet internal and external cockpit operational requirements

- allow mutual supervision (cross checking) among crew members

- enhance a team (crew) concept for configuring the plane by keeping all crew members ‘in the loop’

- dictate the duties of each crew member in order to facilitate optimum crew coordination as well as logical distribution of cockpit workload

- serve as a quality control tool by flight management and government regulators over the pilots in the process of configuring the plane for the flight.

Checklists can be highly effective. Author and surgeon Atul Gawande devised a simple surgical team communications checklist for use in operating theatres. ‘We implemented it in eight hospitals. The average reduction in complications was 36 per cent,’ he told the Harvard Business Review. ‘We cut deaths by almost half, all those results being highly statistically significant.’

Despite the impressive results Gawande found resistance to his checklist among some surgeons and hospitals. Checklist use is better established in aviation, but checklist non-use is a distressingly common factor in accident reports.

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) published a comprehensive review of factors affecting checklist use in its report into the crash of a Beechcraft Super King Air 200 at Essendon in February 2017.

In its review of prior studies, the ATSB identified four reasons why checklists are not always completed:

Attitude: Hawkins (1993) highlighted that, ‘probably the greatest enemy of error-free, disciplined checklist use is attitude—a lack of motivation … to use the checklist in the way it should be used’.

Dagani acknowledged that attitude to checklists was an issue and had this to say. ‘The checklist must be well grounded within the “present day” operational environment, and the operator must have a sound realisation of its importance instead of regarding it as a nuisance task.’

Distractions and interruptions: Distractions and interruptions can result in a disruption to the sequential flow of the checklist. This not only means that the pilot will have to memorise the location of that disruption, but it may also lead to a checklist error or omission.

Expectation and perception: When the same task is performed repetitively, such as a checklist, the process becomes automatic. The user will create a mental model of that task, and with experience, this model will become more rigid, leading to faster information processing and the ability to divide one’s attention. While this will ultimately reduce the user’s workload, this model may adjust or even override ‘seeing what one is used to seeing’.

Degani & Wiener interviewed many pilots who commented they had seen a checklist item in the improper status but perceived it to be in the correct status. For example, the flaps were set at zero, but the pilot perceived them to be at the 5° position as this was what they were expecting to see.

This happened in the case of Spanair flight 5022. After not setting the flaps in the after-start checklist, the crew ran through the take-off briefing (taxi) and take-off imminent checklists (including a final items step) but did not notice that the flaps were up. The McDonnell Douglas MD-82 crashed, killing 154 of the 172 on board.

Time pressures: The speed of performing the checklist may affect the accuracy of the check. For example, if a pilot scans the item to be checked quickly due to time pressures, the accuracy of the pilot’s perception will degrade, and the possibility of error will increase.

An extensive jump-seat observation study by Dismukes and Berman identified 899 deviations in 60 flights, of which 22 per cent were related to checklist use. Checklist deviations were mainly associated with the pre-taxi, taxi-out, descent and approach phases of flight.

They found six types of deviation.

Flow-check performed as read-do: Normal checklist procedures generally require pilots to check and/or set the items in a sequence or flow. After completing this flow, the checklist is performed to confirm that the critical items have been correctly actioned. However, if the flow is not performed and only the checklist is completed, items not on the checklist will be omitted.

Responding without looking: The authors described two situations when this may occur. The first is when a pilot responds from memory of having recently set or checked that item as part of the flow. Basically, the current situation may be confused with the previous situation. Secondly, a pilot may look directly at the item to be checked but perceive it to be in the correct position when it is not. A pilot may respond without looking due to habit or when under time pressure.

Checklist item omitted, performed incorrectly, or performed incompletely: The pilot’s response is incorrectly worded, one or more elements of a multi-item response are omitted or combined into a single response, or the checklist is not verbalised completely. The research found that while in some cases the checklist item was deferred and later forgotten, in other instances the checklist was interrupted by external influences and an item was disregarded. In contrast, on many occasions an item was omitted when no external disruption occurred.

Poor timing of checklist: The checklist is conducted at the wrong time or at a time that interfered with higher priority tasks, or it was self-initiated at the incorrect time.

Checklist performed from memory: Similar to that identified by Degani & Wiener (1990), when a pilot has completed a checklist many times, performance becomes mainly automatic, fast and fluid, and requires minimal cognitive effort. Forcing oneself to read each checklist item may be awkward, effortful and time-consuming. Therefore, pilots may be inclined to perform the checklist from memory rather than from the physical checklist.

Failure to initiate checklists: Failing to initiate a checklist may be the result of distractions, other competing demands on the pilot’s attention, or due to circumstances forcing procedures to be performed out of sequence.

Checklist design

Intuitively, the length of a checklist and the level of discipline in using it must bear some relation. Over the history of aviation, checklists have swelled and shrunk. The all-time record holder for complexity will probably remain the Convair B-36.

It took the ground crew six hours to prepare this 10-engined Cold War strategic bomber for a mission, after which the flight crew took another hour for a preflight check of 600 items. Automation and an appreciation that safety and simplicity are linked have led to the checklists of modern aircraft shrinking. On aircraft with Garmin’s G1000 glass panel, for example, there is the facility to have the aircraft’s strobe beacon come on automatically at engine start, removing an item from the checklist.

Gawande, an eloquent advocate for medical checklists, says there are good checklists and bad ones. ‘Bad checklists are vague and imprecise. They are too long; they are hard to use; they are impractical. They are made by desk jockeys with no awareness of the situations in which they are to be deployed. They treat the people using the tools as dumb and try to spell out every single step. They turn people’s brains off rather than turn them on.’

‘Good checklists, on the other hand, are precise. They are efficient, to the point, and easy-to-use even in the most difficult situations. They do not try to spell out everything—a checklist cannot fly a plane. Instead, they provide reminders of only the most critical and important steps—the ones that even the highly skilled professionals using them could miss. Good checklists are, above all, practical.’

Final check: the killer items

There are two lessons from this story. The first, obviously, is use your checklists. But be aware that how you use them is also important. They reduce but do not eliminate human performance variation.

The second is that checklists must be designed well, not as shopping lists of everything that might need to be done, but as error traps, for the smaller range of things that can kill you.

Further reading

This Day in Aviation. 30 October 1935. See: https://www.thisdayinaviation.com/30-october-1935/

Flightglobal/Archive. See: https://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1936/1936%20-%200070.html

Air & Space. B-36: Bomber at the Crossroads. See: https://www.airspacemag.com/history-of-flight/b-36-bomber-at-the-crossroads-134062323/#VU41bySC5wAmW8Or.99

Gawande, A, (2009). The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right. Henry Holt and Company, New York.

Comments are closed.